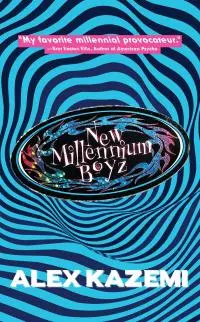

It hinged on suspicious; suddenly, me and other authors I know received a book called New Millennium Boyz by Alex Kazemi in the mail. It wasn't to fish for blurbs either—they had it more than covered with Douglas Copeland, Poppy Z. Brite, Douglas Rushkoff, and Shirley Manson providing glowing testimonials, and then in bright pink there's Bret Easton Ellis at the top calling Kazemi his "favorite millennial provocateur." Who the fuck is this Kazemi guy and where did he get all this praise? I scoured the socials for him—nothing except a mysterious shirtless twink "intern" shilling his book relentlessly, kissing the camera when not speaking in Zoomer code on Kazemi's behalf. It was getting so weird I began to think it was all an intricate persona con ala JT Leroy (who also blurbs the book), then I grew paranoid his PR saw me and these other authors receiving advanced copies as some kind of alt-lit influencers, a fate worse than death, obviously... to which I then began to question my persona, then my whole existence in this increasingly suffocating microcosm.

Then, I cracked the book, immediately challenged by its overarching style; a corporate branded love letter to the late 90s/early 2000s in diary form; its characters overenthusiastic, repellent with coming-of-age sentiment. I soon realized what was actually unfolding: an unfiltered yet sharp satire of that very thing, an endurance piece I was unable to put down—like the most condensed sugary candy hitting the nerve of a forgotten cavity, shooting a searing pain into your mind once you see the power dynamic of Brad and Lu is really going for the throat. Kazemi has written a totally unique, dialogue-heavy and philosophy-riddled commentary on idle-handed peer-pressure, on surveillance and selfies, on what we sacrifice when we achieve popularity—the latter of which Kazemi is often challenged with, or perhaps challenges, in real life.

To be fair, our literature scene can be deceptively insular and let it be known Kazemi didn't just come out of nowhere. While NMB is his debut novel a decade in the making, he's the author of the non-fiction manifesto Pop Magic: A Simple Guide To Bending Your Reality, which, could be argued, picked up where Thee Psychick Bible left off. Kazemi was also the editor of The Advisor, a "digital platform featuring handwritten open letters penned by contemporary male icons to young men" (that featured letters from Richard Kern, Bruce LaBruce, and Moby) among countless other credits to his name.

NMB is being called “the most dangerous book of the year.” Is this something you stand behind, or is there a whole other “danger” of your debut, which has absolute literary merit, being reduced to sensationalist tags? What are some ways you personally think NMB is dangerous? Can a book even be dangerous? Should we call our own ideas dangerous, or are we siding with the censors, the book burners, and pastors by doing so?

I don’t think the book is dangerous, or edgy. Dennis Cooper has happened. Bret Easton Ellis has happened. Chuck Palahniuk has happened… I’m not the creator of this genre. Honestly, it’s very cringe to me the book is being marketed as "dangerous" or "high-risk literature." Eye roll. We live in the time of the internet, where thousands of authors everyday can freely publish the most deranged, unhinged, uncensored stories and sell dozens of books. I think this was my biggest war with my publisher, I honestly thought because of all the famous authors that have paved the way for this type of creative freedom to be commonplace, that this wouldn’t be a thing.

I guess New Millennium Boyz is perceived as dangerous because a lot of the current literature that mainstream publishers are pushing doesn't really challenge the reader, or cause for any inner examination. The mainstream literature of 2023 usually obeys a political dogma, or consensus and this may be breaking some of those rules, but I’m not the first person to break them. I don’t think literature should make you feel comfortable or safe, but who am I to say I’m a "dangerous writer?" I’m just a dude who wrote a novel, the truth is that boring. Sorry. I don’t feel like I have any literary peers or am part of any "scene" or "online community." The reason I wrote this book is to hopefully bring joy to readers, make people feel inspired to create or to make young men feel less alone in their own pain and to have millennial men reflect on the collective culture that informed their identities while coming of age. Maybe, make some new friends who are kindred.

I guess New Millennium Boyz is perceived as dangerous because a lot of the current literature that mainstream publishers are pushing doesn't really challenge the reader, or cause for any inner examination. The mainstream literature of 2023 usually obeys a political dogma, or consensus and this may be breaking some of those rules, but I’m not the first person to break them. I don’t think literature should make you feel comfortable or safe, but who am I to say I’m a "dangerous writer?" I’m just a dude who wrote a novel, the truth is that boring. Sorry. I don’t feel like I have any literary peers or am part of any "scene" or "online community." The reason I wrote this book is to hopefully bring joy to readers, make people feel inspired to create or to make young men feel less alone in their own pain and to have millennial men reflect on the collective culture that informed their identities while coming of age. Maybe, make some new friends who are kindred.

As a cusping Gen Xer, I found NMB to be a very definitive account of the millennial experience, or rather, how I imagine it would have been. I feel millennials might be the most criticized yet misunderstood generation. What makes that era of youth so unique, compared to ones that came before or after?

As a Gen X cusper, you were born in the late 70s, so you are closer in age to someone like Fiona Apple. I guess, you must’ve been around 22 in the time period the book is set in, so I’m sure you have a lot of fragmented memories of the era or could resonate with the references in this book. The reason I think the Y2K-era was unique for adolescence is because of the cultural arena that existed. It wasn’t 950 different algorithms competing for your attention. Corporate boomers could sell products to teenagers as they watched their favorite MTV shows, bands could become rich from PR marketing, books could blow up because of daytime talk shows. This was a controlled arena for people in America to become products, and also mimic the human-products being sold resulting in a loss of identity. I also think so many millennials came of age with a unified feeling of participating in a subculture, or niche-moment in pop culture, and that seems to be totally gone. Of course, the birth of the early internet, changing the way we communicate and blurring the lines between the public and private self due to online expression.

When I first started reading NMB, I was distracted by the bombardment of nostalgic product placement, the same way I’m turned off by a show like Stranger Things that weaponizes sentimentality for viewership. But then I considered a novel like Glamorama by Bret Easton Ellis, which is also mentioned in NMB various times, and I began to rethink and understand your approach—NMB being a decisive over-the-top avalanche of this, which I imagine how it felt growing up in that time, with the lengths corporations were going to exploit youth’s attention spans for capital. By the end of NMB, I found there to be a real poetry in those trivial brand names swirling into coming-of-age mania and suffocation. Was this a conscious effort? Do you see millennials defining themselves by what they consumed?

I’m happy you were distracted by the bombardment of nostalgic product placement because this was the exact reaction I was fishing for. I was trying to create the sensory assault that is so associated with adolescence in the Y2K era, but also was trying to mimic today’s current obsession with the 1990s/Y2K. We’ve never lived in a time where you can see so many of the same references inundated into your subconscious mind through social media feeds, all the big culture sites do "90s throwbacks" to get clicks. I was very repulsed and exhausted by this. I appreciate you finding poetry in pop. This was definitely a calculated decision on my part and I wanted to consciously build a suffocating feeling of emptiness and "the void," contrasted with the more sad heartaches the boys have. Honestly, I set out to write a book that was an absurdist response to the "extreme-teen genre." I wanted to see how far I could take the "coming-of-age" genre that is so associated with this era and obsessed over in artsy circles, like Larry Clark’s Bully, and ramp it up. If the book is provocative to the reader, then that has more so to do with them and their own thresholds than with what I set out to write.

I just saw a headline for NMB that claimed it upset corporate sales reps and allegedly triggered a walkout as a result of its “controversial” content. Did this really happen, and if it did, who were said corporate sales reps outside of your publisher? Did this have anything to do with its rumored option for film?

Yeah, unfortunately this did happen and I think it’s annoying and ridiculous. During copy edits, people were offended by the usage of two Columbine victims names, a historical fact by the way. The character wasn’t even saying it in an "offensive" or "degrading" manner, it was more of an exploration of the liberal-thing of knowing victims names and spamming it on Twitter as a virtuous move. I was trying to show that a human’s narcissistic attachment to their own morality is the same despite whatever time period we are living in. But yeah, I probably can’t say, I’ve gotten in enough trouble with them and I just want the novel to make it to stores in peace.

If you are referring to the recent controversy, I guess anything about “Alex Kazemi” doesn’t actually exist, because he’s a simulacrum. He has nothing to do with me, he’s something more ephemeral and he is whoever the person engaging with him creates him to be in their head. I’m the one who has to go through documents that have 150k words full of fragmented notes, ideas, and put it all together and drive myself crazy in isolation creating a novel for a decade.

NMB is very dialogue heavy, consisting primarily of teenagers talking. For a novel that is already causing such a stir, there’s nothing in there I was personally shocked by, because we also heard very real conversations like this growing up in the 80s and 90s. And I think that’s the key phrase—we were still growing, not yet fully developed, so in a way we were trying everything to see what stuck. If a parent were to be shocked by your book, would you suggest maybe they don’t know their children as well as they should?

I agree with you. Nothing in here is new. That was kind of the point. This was just how people talked 20 years ago, for better or worse. This was the natural noise/sound for most boys, and is still today despite of the politically correct culture that tries to ignore those realities. I think parents should be aware of the pressure young men feel to present themselves as charming, clean and sanitized and try to empathize why when teen boys are in groups with other boys, they release so much repressed testosterone-driven behavior. I’m happy you were able to empathize with the characters testing the waters, and how their identities were absolutely more malleable at this time in their lives and I was able to display that process to you as a reader.

You mentioned in your accompanying letter that NMB took ten years to write, which was refreshing to hear when so many authors feel pressured to produce rapid fire to stay relevant or whatever. Could you explain what took so long, or was it a conscious decision to spend as much time on your debut novel so it could be the best it could possibly be?

Authentic and sincere experiences are rooted in being fearless about your honest expressions, even when it can get you in trouble.

I think the reason it took ten years is because I was given a book deal by Viacom/MTV as a teenager, when I was just trying to figure out my voice and yeah sure, maybe some people at 18 can churn out books like Less Than Zero, but I also couldn’t do that. I also couldn’t live up to the expectations of having all these Tumblr teenagers who were waiting for a final version of my book when I had a viral-rough manuscript. Intuitively, I knew I needed time. I had to grow up and grow with the characters, and change through the formative and sad moments of my 20s.

Honestly, I am not that inspired by literature. I was very paranoid about "keeping my voice" my own. I was more concerned with building impactful emotional moments for the reader. I wanted to build something that felt uniquely true to my vision and that process. I was very inspired by magazine long-form essays like vintage Rolling Stone cover stories, films, documentaries, home videos, transcripts. From the start I had a mission: “I want to write a book that is just minimal sharp imagery, and sharp dialogue. I'm not concerned with plot or story.” Me and my publisher fought a lot about this in the beginning, because I had to earn and work to creating a more stylish version of what I originally set-out with, and what I started with. Maybe the next one will take ten years, I don’t know. I hope not. I think I have more of an understanding of what I want my voice to sound like, but I also want to challenge myself and experiment with styles that make me more uncomfortable or are more foreign.

You're outspoken against social media. To most authors, this is like career suicide to be that unaccessible. What is your philosophy regarding this?

I hope it is career suicide. I don't want to wakeup every morning in a narcissistic feedback loop about myself, and repost and share every single mention of my book and be obsessed with navel gazing. I also don't want people to be developing a para-social relationship with me, or feel like suddenly I have to be sharing the music I like, the books I'm reading, the films i'm watching, to keep you interested in me or following me. This is why people have publicists and teams, it's my publisher's job to handle those things. I don't really want to have the pressure of sustaining an online image or to have the private moments of my life become performative. I just want privacy and I think when you even start to give people access to a selective, curated version of yourself, this is also another form of violation. Maybe I'm in a place of privilege to be able to have these opinions but Cal Newport talks about this at great length. I'm not alone in this decision. If anything, I'd like to be a representation to aspiring novelists, to pave a path that feels authentic to them rather than playing everyone else's game.

What would you tell a present day Zoomer in Brad’s scenario in NMB—searching for identity and acceptance from peers, while also wanting to lay waste to the mediocrity surrounding him, making him susceptible to self-destruction? How would a teenager find an authentic, sincere experience these days?

I mean, I feel sorry for the Zoomers but that is probably me just being a geriatric millennial. I think a lot of the painful scenarios Brad gets into because of his own boredom in 1999, the painful isolation and emptiness of wanting to seek for something new—I think that’s probably what a teenage boy does with all his idle time in the 2020s: watching Jordan Peterson vids all day, going on Discord and Pornhub and just sublimating his physical self into a immaterial avatar. I kind of think Brad became an avatar, or an anon "username" when he would hang out with Lu and I think this obsession for power, or control over your own life can bite you back.

What I would advise them: nothing in the material world can satiate you, this is a lower-earthly dimension and trying to search for godlike highs through approval, validation, temporary fixes—it’s never going to work. Authentic and sincere experiences are rooted in being fearless about your honest expressions, even when it can get you in trouble. You have to move with the process of becoming who you are in the way your identity chooses to unfold and try to not be so judgmental of the journey of becoming "you." If you ever get there...

Get New Millennium Boyz at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.