Photos courtesy of the authors

In 2017, novelist Joshua Mohr released the memoir Sirens, about his years of substance abuse, getting clean, fatherhood, and the congenital heart defect which led to a series of strokes that almost killed him.

It was textbook Josh: gripping, thoughtful, and funny as hell. I took a particular interest in the development of the project. The first time he told me about it was after his heart surgery. We were standing outside a bar in Brooklyn where he'd just done a reading. My daughter had recently been born with a congenital heart defect, and I felt a kinship with him over that.

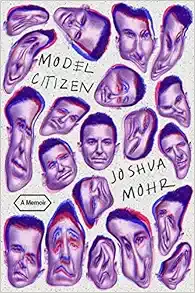

And I watched as a Buzzfeed article morphed into Sirens, published by Two Dollar Radio, before it evolved into Model Citizen, available now from FSG. It's an expansion of Sirens, continuing with Josh's journey through sobriety, relapse, and his continued health issues. And it takes what was already a really bracing, beautiful memoir, and reveals new angles, deeper facets, and a lot more emotional depth.

Josh is also one of my favorite people to talk shop with. We try to see each other when book stuff takes either of us through the other one's hood, and I've interviewed him three times for this site. The last time we spoke was on a long walk around Green Lake Park in Seattle two years ago, while I was in town doing promo. It was a really nice respite in between the madness of Emerald City Comic Con.

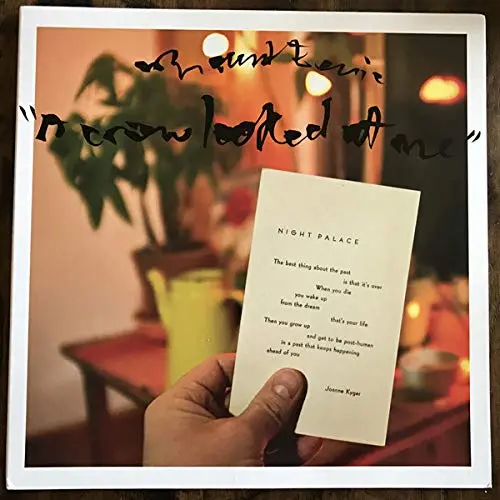

Given the current state of the world, and being that book tours aren't a thing, we couldn't swing a lakeside stroll for this release, so we settled on a Zoom. What follows is a lightly-edited transcript of our conversation, which we kicked off by discussing A Crow Looked At Me by Mount Eerie, a project of musician Phil Elverum.

Elverum composed the album in the aftermath of his wife's death, and Josh referenced the album in Model Citizen. There was some strong connective tissue there, these two pieces of art addressing mortality in a very bold and clear-eyed way, so I thought it would be a good jumping off point...

So yeah, I decided—and I'm sure this is going to thrill your publicist—that instead of talking about the book, we can start by talking about this album, A Crow Looked at Me, which you referenced in the book.

Cool.

So, I guess the first question I have to ask is, why would you want to inflict that much emotional violence on your reader? Because I did exactly what you said, to put down the book, listen to the album, and come back. And I did, and halfway through the first song, I was a sobbing mess.

Yeah, good. You know what's funny, man, and it's great to be talking shop with you, I think that there are two things that really lured me into that riff into the book. The first was, I love The Flaming Lips, and I really appreciate how back in the old days, The Flaming Lips would have these, as legend goes anyways, these sort of outdoor community concerts in various parking lots and vacant lots around Oklahoma City, and what they would do is they would put a part of a song on one cassette tape, and another part of the same song on a different cassette tape, they would all get doled out amongst a bunch of cars and everybody would hit play, “Three, two, one, hit play,” and it became kind of this one cohesive whole emanating from these kind of sovereign parts.

I love the idea that a bunch of people are making one artifact, even though the artifact was actually engineered by The Flaming Lips. That idea has stayed with me over the years, it's so meta. How do you invite your audience as close, not to just the book, but to the book's construction? I want the reader to feel as though she's writing this book right along with me. That was kind of the idea drawing off from The Flaming Lips idea.

The other side of it was when I first stumbled upon that record, someone told me about it, and I wasn't familiar with the guy's body of work, and I listened to this record. And what the record's about is, he had a young wife, he was a young guy, and they had a young kid. And because we live in an unforgiving, relentless place, the mother died at home. She died in one of the bedrooms in their house. She was a musician as well. And when she passed, and while he was grieving, he decided to do the one thing that artists do. We try to process the unprocessable through our art, right? So, he decided to write a record about his grief, around his wife dying in the actual fucking room where she died, and he played all of her instruments while he was composing the music.

So, in a sense, the music is written from inside his ache. He's not writing about his ache. His ache is a setting. That was a thrilling revelation for me. As a writer, how can I try to do something similar in my work, where I'm constantly pointing out to the reader that we're writing this book at the same time? She has to be there right along with me and we're doing all of these things together. I think that's a really exciting thing for me.

This book really felt like it was coming from an ache too, a different kind of ache, obviously. But there was this crushing feeling, reading the book as well as listening to the record, and it makes you think a lot about mortality.

Well, what was interesting about the record that he made, because the room that they recorded in, I would argue that room became a character in the record. So, for example, in Model Citizen, there's a riff early in the action where I watch my young daughter fall down a flight of stairs, and I kind of run the choreography, the nauseating choreography of that moment in painstaking glacial detail. And at the end of the scene, I tell the reader that I'm actually sitting on the stairs with my laptop balanced on my knees while I'm writing. And that happens a bunch of times in the book where I'm just saying to the audience like, "Oh, you thought this was just a set piece? You thought I was just talking about the staircase? No, no, I'm here, and because I'm here, that means you're here too." The same way Phil Elverum was able, via that incredibly melancholic and beautiful music, he was able to make me feel as though I was sitting in that room with him and his wife's ghost while he was recording that record.

And listening to that record felt like reading a memoir, because the way the language was so stripped down and it wasn't, like, flowery bullshit, it was like: you ordered a backpack that you knew that you were never going to see our daughter use, or talking about going to the grocery store and just not being able to exist outside of this feeling of grief around people. And it was so honest in a way that it just drills into the middle of you.

Totally. So, there's a playwright, John Guare, who famously said that life is about surviving the little murders of day to day existence. I feel like that's what it's like just generally, and then you kind of thrust on top of that sort of tragedy while losing a spouse while you have a young kid. Both of us have young daughters too, so it pushes all these buttons for us as like, well, I'm thinking about it from the father's point of view and thinking about like, "What would I possibly try to do if I lost my wife?" I mean, Jesus, my kid is eight. I don't think I've ever cut her fingernails in her fucking life. There are just some things that dads need help with, man.

After my daughter was born, I was the first to cut her nails, and she had those little tiny, wispy nails, the first ones, and I cut her fingertip and she started bleeding, and I had a fucking breakdown. I just started uncontrollably sobbing because I was like, "I can't take care of this child. She's been here for three days and I already cut her open. What the fuck, man?"

Baby's first trauma. There you go.

You’re right about it pushing buttons, because it's a powerful record no matter what. I feel like it'd be hard for anyone to say that it isn't, but when you got a kid, it really does change your perception.

Well, you know what's funny about Model Citizen, specifically in terms of the conversation we're having, it's the only thing in my career that I didn't try to write. Normally, because I'm an indie guy, I'm not fancy where people are going to give me scads of cash and then I go write a book. I write a book and hopefully I can sucker somebody into taking it once I'm finished with it. But my last book was called Sirens, and it was a very short memoir that I did with Two Dollar Radio, so then FSG reached out to me and asked if I had anything else, if there's more of the story to tell. At first, I just thought it was one of my friends playing a trick on me, but once I realized that she was a real person and we were going to write a book together, I just looked at her and said, "Daphne, I've done so many dumb things, we could write five memoirs together. We'll be fine for material."

But the only reason I'm mentioning that is because, in a sense, I already had the map in terms of how I wanted the book to sound, I just didn't know what necessarily the book was going to be about. I knew that there were some things that I could be writing about. I can find things to write about in any given day, I'm a serial writer. But what happened is, I had another stroke. So, in Sirens, I had three strokes, then I had this heart surgery, and I thought the story was over. Weee, happy ending. And then two years later, I had another stroke, and now they're not even sure if the blood clots are routing through my heart, which they don't know what to do, so obviously, they don't have any idea how to fix. So, that seemed like a really fascinating conversation to be having, from a junky’s point of view, which is I had done a bunch of dumb things, now I try to live on the straight and narrow, but I'm not really fixed.

So, a lot of what the book is about is kind of accepting the fact that, in one way or another, we're all unrepairable existentially, and this was my version of being unrepairable that I wanted to share with the audience.

What’s kind of interesting about it too is... so I'm reading about Phil and his album, and at one point, he says... because the album came out in 2017, it's a couple years removed now, and he doesn't really strongly identify with that level of grief anymore. But it's still a really interesting snapshot of that time, and it's also a really important artifact for his daughter, that she could look back on when she's older and get that emotionality of what it was like when her mother passed.

Oh, yeah, absolutely. And just think of also... I mean, certainly, it's the artifact itself, but also, what a shining and stunning example of love. She's going to have this high watermark that she'll constantly be able to go back and be like, "This is how much my dad loved by mom." How cool is that?

And then, obviously, this is like an artifact for your daughter, when she gets older. And how does it feel presenting this image to Ava, because you're really honest, and you talk about a lot of really incredible things about your own growth and your own development as a person, but you also mugged some guy, and did a bunch of crazy shit. So, what do you hope that she gets out of it when she's revisiting it when she's older?

One of the fun byproducts, and you know this as well as I do, that when you write a book, there are kind of all these things that you hope people are going to comment on, and then there are also the things that you hear that you didn't intend whatsoever. One of the really cool byproducts of Model Citizen... it's only been out about a month or so, but I've been hearing from a lot of women in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, telling me that for the first time, they think they understand how their dad was.

And I'm always thinking about it from the parent's point of view, I'm never necessarily thinking about it from the child's point of view. But man, it just makes my day when I get emails like that, just being like, "He was in recovery, but it was hard for him." I'd never think about Model Citizen as an addiction memoir. It's always going to be called that because everything needs to be called something, and I understand that, but to me, the important delineation here is that this is a relapse memoir. This is a story after you get clean, because I think getting clean is easy, but staying clean is incredibly difficult.

Sirens is basically parts one and two, and the new stuff is parts three and four. And what I wanted to do in parts three and four is force the audience, in a very uncomfortable way, to occupy the mindset of somebody who's constantly triggered by booze and drugs. I wanted their palms to sweat, in a sense, I wanted this to be a monster movie, right? The monsters sloshing around a bottle.

The real palm-sweaty part came with the relapse stuff toward the end, like in the bathroom, and then when you finally sat down and you had the beer. Was it hard to write about the relapses or the attempted relapses?

I don't know if anything's hard for me in terms of being a writer. I'm one of those people who, even if I'm writing about really squalid, really prurient, really deranged things, I love what I do. So, I'm just basically slugging espresso shots, and listening to The Cramps really loudly. And even if I'm writing about really icky things, I usually have a smile on my face. You had asked earlier about what I was hoping Ava to get out of these things, and I think as parents, we're kind of reacting to how we were parented. My father was just this marvelous liar. He had constructed this persona that was airtight and he wasn't going to let me get to know him. Maybe if he had lived long enough, perhaps I would have seen a chink in the armor, but I only got to know the persona. And that's arguably the biggest tragedy that I've ever endured as a person so far, the fact that he never trusted me with the truth.

So, I wanted to intentionally overcorrect, or I wanted to be like, "Look, Ava, you probably don't want to hear about the time when I was 19 years old and robbed a liquor store, but you know what, you're going to," because I didn't get any of that stuff, and now, all I wish is I could get to know who my old man really was. Now that I have a kid of my own, now that I understand how hard this actually is, I would love to be able to pick his brain. So, again, I'm going to put all these things down, and hopefully I live long enough that Ava and I are able to have those conversations later. But if we aren't able to have those conversations, she's not going to be operating with the dearth or the drought of information that I had about my old man.

It's funny because I was thinking about it too in terms of my own work, where it's like, there's a real level of bravery in doing that, because when you're writing fiction, there's plausible deniability. Everything I write it's like, "Well, my character did that. I didn't do that." But you're owning a lot, and it's just funny to think of you sitting there having the time of your life writing about it.

It's really weird, man. I was really glad in the New York Times review of Model Citizen that they picked up on this riff toward the end of the book where I'm talking about what I call cheery nihilism. Typically, nihilism in our society has all these derogatory associations. When I say nihilism in the context of cheery nihilism, it's just a matter of figuring out like, what things in society that you're supposed to care about, but you're not going to fall for those tricks anymore, and that you're not going to walk into those traps anymore. All the narcissistic concerns that a society can make you feel like you're supposed to care about these things. But when your cardiologist looks at you and tells you that you're not going to live out of your 40s, suddenly, you don't care about some of these things anymore. I want to be a good dad, I want to not get divorced again, and I want to make art today. And if I do those three things, and this is the end, so be it. I've had a good life. It's okay.

And so, in a sense, it's this liberating presence too, rather than this like, "Woe is me," on my Tennessee Williams fainting couch being like, "Fuck this, man." If the finish line's coming, I'm going to sprint to it. I'm going to make this day count.

Cheery nihilism just feels like that should be a battle cry of the entire pandemic.

Right? Well, it's like with [author] Pam Houston, we were talking about, at the beginning of the pandemic, she was always like, "Oh, we're figuring out what you've been living like every single day. Every day, your doctors are like, 'Yeah, you might not survive today.'" Everybody, we all knew in kind of this amorphous, vague sense that we're going to die someday, but we just don't think about it every day until the pandemic.

That's true. I covered Hurricane Katrina for the newspaper that I was working for and came back with a mild case of PTSD. I saw a lot of fucked up shit down there, and was sleeping in a tent in a parking lot, and it was a lot. And I got back and would kind of just start crying out of nowhere and was having a really hard time. And I talked to this guy who was a major in Iraq and he worked at the paper too, and I pulled him aside and was like, "I'm having a real hard time with this," and I was trying to explain it to him, and he just put his hands on my shoulders and he looked at me and says, "Now you know you can die."

I love that.

And I felt better! It was like, "Oh, that's what that is. Okay, I get it now."

There are all these lessons to be learned right now, but I'm chewing my nails to figure out if we're actually going to take the time to learn them or not. I think these things can actually be really good things in terms of how we prioritize what matters to us. How many people do you know, when you tell them you're a writer, they're like, "Oh, that must be nice. I wish I had the time to do something like that." Well, paint a picture. And then hopefully, these people realize that you don't have this stash of impossible tomorrows. You've got some tomorrows but you don't know how many you got in that shed out there, so do something. Make something. I make art every day, and that's all I care about. That's for better or worse. I'm not saying it's the best way to live, I'm just saying I dad like crazy, I make art like crazy, and that's really all I care about.

See, I don't get the, "It must be nice to have the time," I get the, "Oh, have you written anything I've read," and I'm just like, "Maybe? Probably not."

I don't know if you found this to be the case too, but do you know, ahead of time, what books of yours people are going to like and what books of yours people aren't going to like?

I found really early on that I've got no barometer for that whatsoever. So, my first book, and the first couple of books I wrote were sort of noir, hard-boiled, dark crime fiction, and they were kind of punk rock, and lots of cursing, lots of drugs, lots of drinking, and I thought I was writing for people in my age group. And what I found was that my mom's friends loved them. And I remember I was at a book signing in, I think Houston, and this woman, she had to be in her 50s, she cornered me and was just gushing over the books. So, I've got this older women fan club and I'm like, I just never would have assumed that...

So, you're big at the nursing home, cruise ship circuit?

Yeah, apparently. Shit, man, that's where I should be promoting these books. But yeah, no, I'm always pleasantly surprised when anybody wants to read something that I wrote, but there are times that it's really surprising who keys into what parts of what I've done.

I'm hoping that that's another thing that we come out of this with. Everyone is so anxious, and everyone is so scared to make art, true art, to put yourself out there. I'm hoping that that's another thing that comes out of this, that people are just like, "I don't need to be careful. Life's too short to be careful. I want to say something about X. Why don't I do that today? Why don't I do that tomorrow? Why don't I seize these things?"

We’re looking at a big reset after this no matter what, and I really am curious about what the sort of long-term mental health ramifications of this are going to be. You know what, maybe if it's some cheery nihilism, that's not so bad.

It should be the era of the zero fucks. Why would we pull a punch now? They just told us that we had to spend an entire year inside, and we did it. And now we're emerging, we should do everything that we want to do.

We need our version of the Roaring 20s after the Spanish flu.

You would look really good in a flapper dress, for sure.

I've been working real hard on my beach body, so yeah, I think I can finally pull it off. So, what are you working on next?

When FSG bought Model Citizen, they also bought my next novel, which is called Get Rich. It's been done for a while. It was done before Model Citizen, but they wanted to do the nonfiction stuff first. It was my first historical book. All my books are kind of about contemporary degenerates. You were talking about how you pitched your next book to your agent and then he had his encoded and idiosyncratic reaction. Here was my agent's reaction. I was like, "I think I'm going to write another bar book." And he's like, "You can't do that." And I was like, "What do you mean I can't do that?" And I was like, "That's what I do, I write bar books." And he was like, "You can't do that anymore." So, I went home and I was like, "I got to figure out a way to do this." And like, "I'm going to write a book set in the Old West. They're going to be in a saloon, but it's not a bar book because they're wearing hats, and they rode up on horses."

You made it work.

I don't think I'll ever write another historical book in terms of, it was really difficult to get right. I spent a lot of time in the San Francisco Chronicle archives, which was really fun, but it took me a lot longer to write this book. Normally, it takes me about two and a half or three years to put a book together, and this took much longer than that. But it's about the first female poker dealer in gold rush San Francisco, and I'm sort of drawing on somebody who was real, so I know just enough about her to get the facts right, but not too much that I'm wedded to all of them too, because I want to make a bunch of stuff up as well.

So, you did Sirens, you did Model Citizen, how does it feel pivoting back to fiction? Did writing a memoir, did it feel like a reset, did it feel just a little different? What is that transition like?

I think it'll be nice to not be talking about myself so much. Again, I wasn't trying to continue the conversation of Model Citizen, I thought that was sort of over. It's weird too to figure out what we want to do as artists, because we want to be ambitious, but we live in this era where we're really kind of rethinking and recalibrating the rules and kind of the aesthetic and stylistic responsibilities about what's in bounds and out of bounds. And hearing the noise and all that can kind of choke me up, so I'm sort of at a zone. Get Rich is finished. I have the time to write something new. I just don't know what that is yet.

Get Model Citizen at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Rob Hart is the class director at LitReactor. His latest novel, The Paradox Hotel, will be released on Feb. 22 by Ballantine. He also wrote The Warehouse, which sold in more than 20 languages and was optioned for film by Ron Howard. Other titles include the Ash McKenna crime series, the short story collection Take-Out, and Scott Free with James Patterson. Find more at www.robwhart.com.