Books come out all the time, from major releases via The Big 6 to all those Kindle-only productions by authors that like to take things into their own hands. The industry is constantly buzzing about who just came out with what and how to get published. In this column though, we’re going to present the other side of the coin: what to do when you lose your publisher. Sometimes this can be rather unfortunate, but other times it’s a blessing in disguise. This is a personal tale in need of some set-up, so let’s begin at the beginning.

The Re-release:

It was January 14, 2011, the second release party for Out of Touch, a novel that played heavily to local nightlife, which made it easy to secure sponsorships, people wanting to jump on this proverbial bandwagon of ‘literature for the socialite crowd.’ My face was all over Ink Magazine that week, touting this two-part soiree that was sponsored by a nightclub, a clothing boutique, a vodka company, a beer company, and a media entity. There was a press wall and photographers and all sorts of people telling me, “Hold the vodka up with the label facing outward.” The camera would flash, and then I’d walk through the crowd of people that all looked at me with some level of recognition—sometimes getting accosted by a random chick who wanted a picture or an autograph, and because I was fairly tipsy, the inscriptions turned out shaky or a bit lewd for the advertised ‘book signing’ portion of the night. So I signed the books, took the pictures, and drank the drinks (label out, of course), and then we migrated to the club to repeat the process in a less professional sense. The evening would take that expected turn to fuzzy, conversations were choppy at best, but all the while I was thinking: You did it right this time.

I had done this before. The original incarnation of the novel was through a vanity press, however, this was before the likes of J.A. Konrath and Amanda Hocking were household names. There was still that stigma of ‘you had to pay to put your work out’ which could only be shaken by traditional acceptance- in this particular case, a new house out of Kentucky known as Otherworld Publications. They were publishing an author friend of mine, and after a very short period of deliberation, had accepted my book to be part of their flagship series of releases. Things were looking up, and even though I knew this was a small house, I took comfort in the fact that I was going to have resources beyond just myself.

The publisher said all the right things: they had an aggressive marketing plan, they were going to get all those interviews and reviews that I hadn’t gotten before, they were going to get their authors on the shelves at Barnes & Noble and Border’s. There was a myriad of ideas and plans of action to be implemented, but in all honesty, I was just happy to be getting a re-release through a traditional house. When I signed the contract, that’s pretty much all that I cared about: the credibility aspect. It never crossed my mind they’d be going out of business in less than two years. Why would it?

Plan vs. Action:

When selling a novel, there are a slew of different methods in which to do it. More often than not, there’s a ‘plan of action’ stage in which the publisher shares their marketing ideas with the author and vice versa. This could be physical mediums like bookmarks and business cards to online-only pushes: website ads, Goodreads giveaways, etc. The goal is to come up with as many marketing tactics as possible to entice buyers (while staying within budget), and in that regard, Otherworld was no different. The problem was execution.

For instance, the party planning: retaining both venues, locking down sponsorships, hiring on photographers and a DJ, and then promoting all of it—the publisher didn’t have a hand in any of that. It was more my area of expertise and there was little they could do to assist me considering their physical distance. During our ‘plan of action’ stage, I made it clear this was something I could do that would yield book sales and promotional footage. It was things like getting reviews and interviews that I needed assistance with. I needed some kind of marketing budget and people getting me on bookshelves. Essentially, I needed the publisher to execute their own list of ideas.

There were interviews, and there were reviews, and there were book clubs in which the novel was featured, however, it was all self-generated. The only thing the publisher brought to the table was an Internet radio interview. I would end up declining that based on hearing another author on the label cold call in to an ‘interviewer’ that had no clue who he was or what his book was about. Beyond that, there was very little done in the realm of this ‘aggressive marketing plan’ that Otherworld often spoke of. There were Twitter and Facebook updates, of course, but nothing that couldn’t be done myself.

I go back and forth on the issue. One part of me wants to believe that the publisher got in over their head and simply didn’t realize how hard the game was; the other part of me thinks they got complacent and left their authors to their own devices, hoping one of them would get hot and the effect would generalize to other titles. What ended up happening was each title sold well within the author’s direct network, but soon after those wells were tapped, there was a tapering-off effect that had the publisher scrambling and pushing us to leave our novels in dentist’s offices and Jiffy Lube waiting areas. They’d send word that they had a ‘new and improved’ marketing plan via email, but there was never any follow-up on that. It was a classic case of overpromise and underdeliver.

The point is not to bitch about the publisher or to showcase an author’s sour grapes; it is to illustrate that it’s just as difficult to break through in the publishing game as it is the writing game. And oddly enough, the main cause of failure in either area is usually the same: inactivity. If you don’t believe that, ask yourself, What happens to the writer that stops writing? What becomes of the publisher that doesn’t promote their titles?

When you stop, you die. Simple as that. So what happened next wasn’t a surprise to some of us.

The Folding Process:

We (the authors) got the email on June 13th, 2012, that the publisher was closing its doors… for personal reasons, which I’m not inclined to disclose. Logic dictates that this was going to happen anyway, what with the lack of promotion and stagnant nature of the press. At first, it comes off like an ‘it’s not you, it’s me’ breakup letter, but that only slightly lessens the blow of the reality: my book is going out of print and there’s nothing I can say or do to stop it. The release party and the photos and the belief that I made some kind of major breakthrough—it was all part of something temporary.

This is the risk you take when you sign the contract, one that most people don’t consider: it could all be over at any minute. Being published is a victory, one that should be celebrated, but this is only the beginning of the very long process that is survival in the industry. There’s always going to be a better author the same way there’s always going to be a bigger publisher. Those that apply their ambition move forward while the weak fold.

So the big question is: what happens next?

Well, there’s always the self-pub route that so many are taking advantage of. In a situation where the product has already been established, there’s no reason why you couldn’t put out the same exact book through LuLu.com or any of the other DIY presses. At the very least, the Kindle-only option would bring in some scratch at little time and expense to the author.

The next option is trying to find another publisher, however, this is only beneficial under one condition: that something can be done with the book that wasn’t done before. If not, the author is once again pitching to the same market that’s already familiar with the book, and you’ll be dredging the bottom of the well before you know it. With subsequent editions of any work, not only is an ‘aggressive marketing plan’ absolutely required, it’s probably best to pair it with the author’s next release. If you’re going to bring something improved to the table, might as well bring something new as well.

Finally, you can do nothing. Yeah, you read that right: do nothing. Well, do nothing in a sense that you’re letting your baby go out of print for the time being. Keep writing, of course, and keep getting published. Sometimes it’s best to focus on the creation of a new product than the second life of an older one as it can lead to reprint offers. To pull from our LitReactor family, Stephen Graham Jones got such an offer through Dzanc for some of his work. Craig Clevenger, after enough fan demand, had his debut The Contortionist’s Handbook put into circulation again by MacAdam/Cage.

Novels never go completely out of print; they just become harder to obtain or temporarily sidelined. Don’t get me wrong, the first time you get that email telling you your book is on its way out, it’s going to cut deep. No matter how you feel about the publisher or how many regrets you have about the current product, losing your deal sucks. First, there's the shock of it, and that's quickly followed by a retracing of steps as to where and how this all went wrong. This is all part of the business though, part of the cycle. Shit like this happens all the time, so dust yourself off and get back into the game. Publishing is one of those things where you only truly lose when you decide to quit.

New Life:

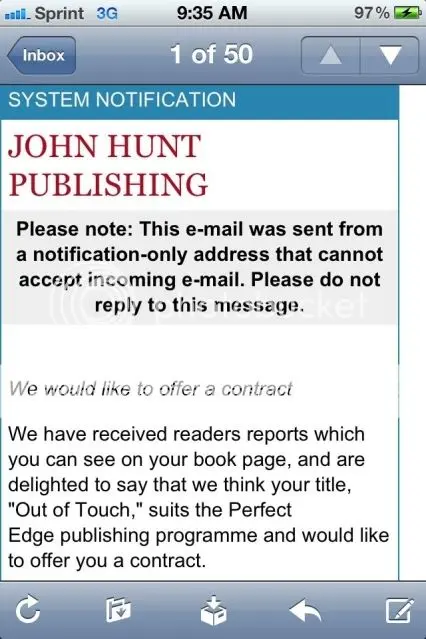

There is hope. You can always come back. In a very interesting turn of events, I had the following email hit my inbox on the day this column was scheduled to post:

And with that, the cycle begins again.