Header image by spekulator

A psychologist always stirs up suspicion at a party. Guests laugh as they ask whether they’re being analyzed, but they’re never quite joking. Should they avoid mentioning their mothers? Not pick up any phallic objects?

A writer at a party is a more ambiguous entity. The unusual job catches people’s attention, but can also make them suspicious – is this a real writer (however they define that), or simply someone trying to show off a hobby like crocheting or painting garden gnomes? Has she written something the other guests should know about? Either way, the conversation quickly moves on to teasing references to “showing up in your next novel.” Like the jokes about being psychoanalyzed, the remark is always made with facetiousness that can’t conceal the sincere curiosity behind it: Will I be in your next book? Am I interesting, memorable enough to be a character? Would I come off well or be the bad guy? More importantly: Should I watch what I say?

When asked, I usually tell people I don’t base my characters on real people, which is sort of true and sort of not. What I really mean is, I don’t usually base a character one hundred percent on a real person. There are some good reasons not to.

Don't write who you know

Too distracting. Focusing on trying to get an exact replica of someone into your book distracts you from your real project – writing a well-rounded character who works in the context of the fictional world you’ve created. Especially if the person you’re modelling your character on is someone you know well, you’re likely to get bogged down in irrelevant backstory. Just because you know that real-life Matt likes to watch tractor-pulling competitions, doesn’t mean your fictional Pat has to. It can be safer to veer towards people you don’t know very well since, that way, you’re forced to fill in the blanks.

Too much baggage. Unless you’re writing a roman à clef and everything and everyone in Pat’s life is supposed to be just like in Matt’s, the two of them exist in totally different contexts. Once you start trying to put Matt in your story, you could find yourself forced to make room for Matt’s last two ex-girlfriends, his godmother, pet rabbits, leaky basement, bowling league and much too much more.

Too embarrassing if (when!) you get caught. This one’s fairly self-explanatory. Unfortunately, I learned it the hard way. I wrote a lot of my early stories without thinking about publication as a real possibility, so I didn’t worry much about how other people would take them. Since editing and submitting both take ages, by the time I’d gotten an offer for a story, it usually felt detached from whatever (or whoever) had inspired it, so I had no qualms about the characters I’d ‘borrowed’ from real life. Unfortunately, the real people weren’t as forgetful. Since I’d changed things to fit the plot, the people often came off much worse than my real-life opinions of them. For example, I’d once noticed a friend being what I called a “ruiner.” We were eating the same dish and I was enjoying mine until she said how gross it was. Not a big deal, but it gave me the idea for a character who couldn’t enjoy anything or let anyone else enjoy it, either. Totally not the case with the real-life friend, but she definitely thought it was after reading that story!

How to do it anyway

That being said, you can and should draw on real people to inspire your characters. Most of what we know about humanity, we’ve learned through our own experiences or other people’s. A fictional character with no resemblance whatsoever to anyone you know probably isn’t very realistic. I mean realistic in a very specific sense here: whether a character’s emotional reactions, trains of thought, decisions, actions, etc. make sense in the context of who that character is and what’s going on around him or her. Sure, your character might be an extraterrestrial blob of slime, but I as a reader would still find it distracting if that blob did something totally out of character. Here are a few things to watch out for when letting real people inspire you.

Plausible deniability. Don’t make your source of inspiration so obvious that no one would believe you if you said you made the character up. Remember, you want to not only write a good story, but also get it published and have lots of people read it (that’s what most of us want, anyway). Knowing certain readers could catch you repurposing a real-life acquaintance might make you hesitate to sell and promote your work as wholeheartedly as you otherwise would. Hang on to what you need for the story, and ditch the rest. Don’t give Matt a name like Pat that’s too similar to his. Change things like job, age, appearance, relationship status, nationality, habits, gender, etc. and Matt will immediately be harder to recognize. That way, when someone says, “This old woman Patricia in your book sort of reminds me of Matt,” you can just say, “Huh, why’s that?” and be off the hook.

Pick and choose. As I said above, real people come with a lot of baggage: their life experiences, character traits, mannerisms, appearance, habits, relationships, career, family, friends, pets, geographic location… When you go to the grocery store, you don’t just have them fill a dump truck with everything on the shelves and empty it onto your front yard; you pick out what you need. Handle Matt the same way. Keep his pained smile and nervous habit of drumming on his fingernails, and ditch that kleptomaniac he used to date and the way he always spoils the endings of movies. Or the other way around. A character you haven’t fleshed out yet is like a hole in your story. Make sure you fill it with the right material.

Mix and match. Okay, so borrowing from real people is about getting the traits you want and leaving out what you don’t need. But why stick to just one inspiration? Jenny’s breakup gave you the idea for a short story, but you’re more interested in how someone with Jane’s temper and Bill’s history would’ve handled it? The more the merrier, as long as these characteristics come together organically and work in the context of your story. The same rule applies here as to the alien blob of goo above: consistency. A character can always grow and develop over time, but his thoughts, feelings, actions, and even growth and development have to be consistent with what we know about him. This is especially important if you’re writing in a first-person or close-third perspective where the reader has access to the character’s interiority.

What about you?

One good thing about basing characters on yourself is that you’re less likely to offend someone that way. Unless, of course, you have your character repeat a bunch of offensive thoughts you usually keep to yourself. The advantage of using yourself is that there’s no one you know better: You have more insight into your own thoughts and feelings than anyone else does, and more insight than you have into anyone else’s thoughts and feelings.

One good thing about basing characters on yourself is that you’re less likely to offend someone that way. Unless, of course, you have your character repeat a bunch of offensive thoughts you usually keep to yourself. The advantage of using yourself is that there’s no one you know better: You have more insight into your own thoughts and feelings than anyone else does, and more insight than you have into anyone else’s thoughts and feelings.

But there are disadvantages, too. You’re just one person with one set of experiences. Every writer knows about the experience of being a writer, but imagine how boring it would be if the protagonist of every single novel were a novelist. Some writers like Jack Kerouac and Charles Bukowski modeled the protagonists of most of their work on themselves, but again, I’d argue that a roman à clef is a special case because you want to take on a character’s life with all the trappings. What works well in a fictionalized storyline may not fare as well in a truly fictional one.

Another risk factor is your perspective. Sure, we have a lot of insight into our own inner workings, but how aware are we of how we’re perceived by others? What we see when we look in the mirror isn’t the same impression we create on other people. It’s sort of like hearing a recording of yourself speaking – not only does your voice not sound the way it does to you, but what you hear the recorded you saying doesn’t sound like it did when you were saying it.

There’s also the risk of taking things for granted. Since you host a tea party with your collection of My Little Ponies every morning, you may think that’s a totally normal thing to do that requires no explanation, but readers may not see it that way. The point is, only use traits you can be objective enough about to know how others will perceive them.

It goes both ways

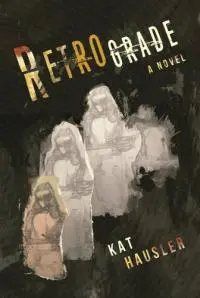

It’s up to you whether to let this inform your writing, but be aware that, regardless of how much or little of yourself and your acquaintances you put into you writing, a lot of readers will assume that your characters reflect you – not just your writing, but your personal life. A coworker who recently started my novel Retrograde said, “Now I’ll know you really well,” as if I’d poured all my secrets into it. Even a close friend who’d already read it told me, “I recognized so much of you.”

Since it’s a novel about a woman whose ex-husband takes advantage of her amnesia to pretend they’re still together, I wondered just where this me-character was hiding. Did she think I was the kind of person who’d exploit someone else’s brain damage? Or that I’d pretend not to know about the past three years in order to avoid facing the facts? More than any of these things, it was most likely (I hope) the themes of the novel that seemed familiar to her: my interest in how the past shapes us, how people deal with awkward truths, and the inner workings of complex relationships. Writing a relationship is much like writing a character, and as with individual characters, I drew on many different relationships – mine and other people’s, romantic and otherwise – to flesh out the marriage in my novel, because it would embarrass me to write about one of my own relationships, because it would distract me from literary aspects, and because there’d be way too much baggage.

So the next time people at a party ask whether you’re going to write about them, just say: “No. Yes. But only as much as I need to, sometimes, when it makes sense, and I’ll throw in enough other people that you won’t be able to tell for sure.” After that, they’ll be happy to go back to talking to the psychologist at the other end of the buffet.

Get Retrograde at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Originally from Virginia, Kat Hausler is a graduate of New York University and holds an M.F.A. in Fiction from Fairleigh Dickinson University, where she was the recipient of a Baumeister Fellowship. Her work has been published by 34th Parallel, Inkspill Magazine, All Things That Matter Press, Rozlyn Press, and BlazeVOX. Her novel Retrograde, published by Meerkat Press in September 2017, was long-listed for the Mslexia Novel Competition. She works as a translator in Berlin.