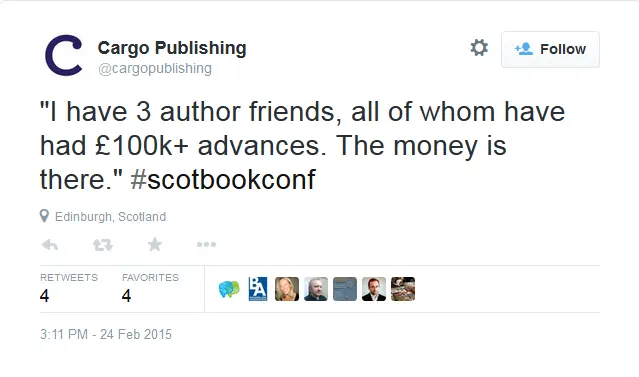

Yesterday I saw this tweet.

And my reaction wasn’t all YAY and WOOHOO and SHOW ME SOME OF THAT MONEY BABY. My reaction was more like Oh God here we go again. You see, it wasn’t always this way in publishing. For years and years, writers were paid an adequate and regular sum for their books. Advances ensured that writers got to eat while preparing their next book and those who sold the most books made more money via royalties. Publishing didn’t make anyone rich, but it didn’t make anyone poor either.

Then came the 1980s. Then came Wall Street and Greed is Good. Publishing took off its wooly cardigan with the elbow patches and put on an Armani and a Rolex. Advances stopped being a way to keep authors from selling their children when times were hard and started being a PR gambit. Spending big money on unknowns became a wall pissing contest, a way of demonstrating who had the deepest pockets and the steadiest nerve.

Then came Amazon and eBooks and 2008. The publishing industry took off the suit and clad itself in sackcloth and ashes. For a while it seemed publishing had divested itself of its six figure habit, but it looks like the crack pipe is back in the addict’s mouth. It’s time for an intervention, because six figure advances shorten careers and crush dreams and here is why.

They don’t make financial sense

From a strictly business point of view (and writing as someone who has run a successful business, though granted, this was in software, not publishing), the logic behind big advances for debut novels is hard to unravel. A debut author has no track record, no evidence that their product will sell. Sometimes their book rides on the wave of popularity created by a predecessor—and you know which ones these are, because the words ‘the next…’ or ‘for lovers of…’ will crop up in the publicity material. But if the blurb uses the word ‘startling’ then you know this novel doesn’t even have any recent comparators to bolster the idea that anyone, anywhere is going to want to read it.

Long story short: big advances for fiction debuts — even those which are ‘the next’ Fifty Shades of Harry Twilight, even those spinning off a popular blog or platform — are a shot in the dark. In business terms, using this as a strategy for long term growth is like taking all the money Aunt Doris left you in her will, driving off to the nearest track and betting the lot on a horse which has never run a single race.

While entrepreneurs sometimes take risks, they do this a lot less often than they like to pretend in interviews, and those with the best track record usually invest in something which we need rather than just want*. Books have no value other than in terms of how much we like to read them — we can’t eat them, or wear them, or shelter from the cold in them — and if you want an example of how ephemeral ‘liking’ can be, ask the owner of a Beanie Baby collection how much their prized rarities are worth now.

They lead to PR overkill

Big advances do serve some purpose. They grab attention, and in a world where everyone is trying to grab everyone else’s attention pretty much all of the time, handing out a wad of cash to an unknown isn’t a totally terrible way to carve out a small slice of airtime.

More terrible is what sometimes follows. Having backed a particular horse, publishers find themselves in a precarious position. What if the nag develops a bad case of spavins and limps over the finish line a poor second? If that happens, your bold PR strategy suddenly doesn’t look so much bold as insane.

If sales aren’t matching the advance, the publisher has two choices: 1) quietly chalk that one up to experience 2) throw good money after bad. Surprisingly many choose option 2 and in an attempt to persuade themselves that the reason sales are disappointing is not because we the public have decided the book isn’t very good, it’s because we the public haven’t heard about it enough, put the PR pedal to the metal. Here is the result. Oh dear.

They skew marketing budgets.

Setting up cages in Piccadilly Station doesn’t come cheap, and because pies can only be cut into so many slices, the more a publisher spends on one book, the less cash and time and effort remains available to devote to all the others. This means that for every book you hear about because it’s billboarded on taxis and gets entered for prizes, there are a hundred which you the reader will never see, because their marketing consists of well, zilch, really.

Okay you can say, well that’s survival of the fittest. The midlist books might not get the promotion of a lead title, but they all get the same chance to catch someone’s attention and acquire their audience through word of mouth. But going back to the racing analogy, this strategy is like failing to put jockeys on any of the horses, apart from the favourite, who gets not only a rider, but also receives the premium hoof care package, dietary advice and regular equine massage. The other horses in this race get the occasional carrot if they are lucky and, once the gate goes up, are left to find their own way round the track. Yes, some of them will, by sheer chance, head in the direction of the finish line, some might even cross it, but most of them are probably going to wander off to the VIP area and eat the flower arrangements instead.

They deprive the reader of an opinion

When a publisher hands out a big advance to a debut, it also sends out a silent, but clear message to the reading public. THIS is the book you are going to like. THIS book is better than all the others in its class. THIS is the book which will make you drop to your knees, shedding tears of gratitude that God blessed us all by bringing its author into the world.

A big advance makes a hyperbolic claim about a book’s value. We’re used to hyperbole and for the most part we accept it as part of the price we pay for having an advertising industry. For products we actually need (see Aristotle below again), like cars, cleaning products and greasy fast food, a little hyperbole is forgivable, but for books, which many of us happily live our whole lives avoiding, hyperbole is a crass misdemeanor akin to having a strip show leaflet shoved into your hand as you pause on a Vegas sidewalk. Those of us who read do it because we like to exercise our brain muscles. We’re thoughtful types who have developed a little taste over those long years we spent in our bedrooms having books as friends. We resent being told that we’re going to LOVE a book before we’ve even had a chance to check out the front cover and the blurb. Big advances do the choosing for a group of people who prefer to choose for themselves.

The result is often a huge pile of wasted effort. However hard a publisher gets behind a book, when it comes to purchasing decisions, readers are as sensitive as Persian cats presented with a new type of kitty chow, ready to stay away in droves at the slightest hint of overselling.

They ruin careers

To most writers, getting a six figure deal is the stuff dreams are made of. When not tweeting our thoughts to an uncaring world or arguing with bigots on FB, we spend hours thinking about how wonderful we’re going to feel (and how our enemies will hate us) when we open the envelope with that big fat cheque inside it.

And there the story ends. We get the cash, we live happily ever after. Right?

Or perhaps not. Out there in the real world, ‘success’ doesn’t actually mean what we think it does (lots of friends, public esteem, suddenly improved looks). It actually means ‘pressure’. Pressure, which always arrives on your doorstep with its ugly relation ‘stress’ in tow, forms the heavily under-reported consequence of hitting it big. In this unusually honest interview, Neil Pollack describes how success pushed him into making one bad financial decision after another. Every six figure advance left him a little deeper in debt and a little more creatively played out. Read it carefully and note that when Pollack does eventually start to sell books, he does it with a publisher who offers him an advance which consists of a big, fat zero.

Which isn’t to say that writers shouldn’t get paid. Writers need to eat, just like everyone else and even if books fall under the use-value of pleasure instead of necessity, books still have the capacity to make the world wonderful. We need to pay people to produce them, but the irony is that on the other side of the big advances, stand a whole lot of authors who make less than a living wage.

So here’s a final thought and kind of a plea to those publishers who have the money to spend big. If a book’s worth publishing, it’s worth publishing well. Instead of dividing up your product into front runners and also-rans, why not devote the same care, attention and money to all the horses in your stable? It worked in the past. It could work again now.

*According to Aristotle, objects acquire ‘use-value’ to humans because they are ‘necessary, useful or pleasant in life’. Food is necessary, cars are useful, books are pleasant. The use-value of these objects can be ranked accordingly and probably has a significant bearing on how safe an investment they make.

About the author

Cath Murphy is Review Editor at LitReactor.com and cohost of the Unprintable podcast. Together with the fabulous Eve Harvey she also talks about slightly naughty stuff at the Domestic Hell blog and podcast.

Three words to describe Cath: mature, irresponsible, contradictory, unreliable...oh...that's four.