Original photo public domain, via Wikipedia

Here is a beautiful coincidence: my eBook version of Ayn Rand's lectures on The Art of Fiction has a typo that tells you everything you could wish to know about what makes a poor writer. See if you can spot it:

Literature is an art form which uses language as its toot.

Language as flatulence. Literature that relies on a lot of hot air being blown in all directions.

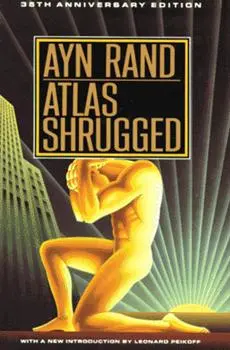

Ayn Rand is the author of Atlas Shrugged, one of the most embarrassing novels to be caught reading. She also gave us The Fountainhead, the most elaborate apology for fascism ever written. While I am indifferent to Atlas Shrugged (it is Objectively Bad), I have a fondness for The Fountainhead because it's so sweetly unaware of what it represents. That's my disclaimer. I'm not a fan of Ayn Rand's novels, and her politics equate to pissing in public because I goddamn built this street in the first place, plebs.

But Ayn Rand does have something to teach us. Let's focus on the first two chapters of The Art of Fiction. Look at this passage:

I can give the reason for every word and every punctuation mark in Atlas Shrugged — and there are 645,000 words in it by the printer's count. I did not have to calculate it all consciously when I was writing. But what I did was follow a conscious intention in relation to the novel's theme and to every element involved in that theme. I was conscious of my purpose throughout the job — the general purpose of the novel and the particular purpose of every chapter, paragraph, and sentence.

Forget the stupidity of that opening remark — that she can tell you why every punctuation mark is where it is in her big, big book. If you take that seriously, you also have to believe her masterpiece assertion that "In regard to precision of language, I think I myself am the best writer today" — and believing that, well, that would cause the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland to blow up because you can't just rearrange the universe however you want to, Ayn. The value of that passage comes from the confidence she shows when she discusses her novel. It's a bad book. It's not as bad as certain people pretend, but it's not a good book by any stretch of the mind. But Ayn Rand defends it, and believes in it unconditionally. She's a hero to herself, and a complete monster to everyone else — and millions of people buy her books even today, lured in by the myth she created.

Forget the stupidity of that opening remark — that she can tell you why every punctuation mark is where it is in her big, big book. If you take that seriously, you also have to believe her masterpiece assertion that "In regard to precision of language, I think I myself am the best writer today" — and believing that, well, that would cause the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland to blow up because you can't just rearrange the universe however you want to, Ayn. The value of that passage comes from the confidence she shows when she discusses her novel. It's a bad book. It's not as bad as certain people pretend, but it's not a good book by any stretch of the mind. But Ayn Rand defends it, and believes in it unconditionally. She's a hero to herself, and a complete monster to everyone else — and millions of people buy her books even today, lured in by the myth she created.

I'm convinced, irrationally and in an entirely non-Objectivist way, that in talking about anything by Ayn Rand you stand to gain a good deal, intellectually. Almost every single one of her oracular pronouncements is a problem. Ayn Rand herself is still a problem. She said things, and she said them so cruelly and unsubtly that it's difficult not to laugh, think, vomit and grow all at once. If you want an education in how to talk about the craft of writing, you can't afford not to pay attention to Rand. Her intelligence was wasted on her "art", but the nonsense she said in justification of that "art" will irritate and rouse to passion even a Zen monk:

The "nonobjective" is that which is dependent only on the individual subject, not on any standard of outside reality, and which is therefore incommunicable to others. (…) The best-known example of a nonobjective writer is Gertrude Stein, who combines words into sentences without any grammatical structure or meaning. She is still to some extent laughed at, but people are laughing rather respectfully… (…) A writer who is not laughed at, but taught in universities as something very serious, is James Joyce. He is worse than Gertrude Stein; going all the way to the ultimate in nonobjective writing, he uses words from different languages, makes up some words of his own, and calls that literature.

I'll refrain from making any wisecracks about Ayn Rand's dismissal of Stein and Joyce, because by the logic she establishes in that first sentence, her conclusion is hard to argue with. If "nonobjective" writing is writing that focuses on the individual and makes no consistent reference to the Outside, then sure, Joyce and Stein are difficult grapes for someone like Rand to digest. But the idea that something "incommunicable to others" would be without merit is a troubling one. I think, in fact, it's an impossible idea for me: an idea that just makes no sense at all, and the senselessness itself is probably incommunicable to others. Rand treats language as a potentially pure and transparent medium through which we can say exactly what we want to say. I take issue with that, but I'm a little ant compared to the hardcore theorists of the 1960s and 1970s who also took issue with it. If language really does have that potential for crystalline clarity and unfailing precision, then maybe we should consider writing "objectively" after all.

But even our daily experience shows otherwise. I can hear the sentence "Thanks a lot" in a way entirely opposed to yours, if you're saying it sarcastically and I'm not clued in to the sarcasm. In Rand's world, perhaps, the context (the objective reality being described) would make it clear whether you're saying "Thanks a lot" sarcastically or not. Fair enough. But objective reality is not as easily defined as Rand pretends. If it were, maybe we'd already agree with her in the first place. Whatever you make of these seeds of a debate, it's worth thinking through Rand's propositions. They're not neutral, and they're not meant to win her any friends. That means they are difficult to ignore. James Joyce used language in an exceptionally elastic and "unrealistic" way, but in so doing he showed us just how much more you can do with language than Rand admits. You can turn language into a musical instrument, a scythe, a guillotine. For Rand, language, and in particular the language that makes "literature", should be used only as a scalpel. I assume she would have us read Atlas Shrugged as a model of conciseness. I find the prose of that novel extremely tedious and uninspiring — not the kind of style that would have made me want to be a writer in my teens, in any case.

But to be fair to Rand, the language in Atlas Shrugged, in its exceptional banality, is clear, accessible, and mostly concise, if you read it uncritically. It's boring, but it does convey Rand's clinical and unemotional mind quite accurately. It's a weird irony, but the stylistic ponderousness of Atlas Shrugged is indeed a reflection of reality: Ayn Rand's reality, the Objective External World to which she was so fond of referring. If there's a problem here, it's that "reality" is a difficult thing to define, and the only reality shown in Atlas Shrugged is Rand's reality, the world as she saw and tried to shape it. In other words, in the couple of weeks it can take you to read Atlas Shrugged, you're stuck ignoring the prose and trying to make sense of the "ideas" themselves. One point for Rand: her language, her prose, is so ignorable that you really do have to focus on the world it's trying to evoke.

Rand didn't mean "toot" but "tool": Literature is an art form which uses language as its tool. The problem with this is that there is an emphasis on the word tool, but no elaboration whatever on what art should be. We understand, from reading on, that using language as a means in itself is a no-no, but that's when a difficulty emerges. If literature is an art form using language as a tool — what is it using this tool for? What is it building? Rand made her literary career out of telling us epic stories about very simple but unpopular ideas: Man has a duty to himself first, and so on. But is that what art is, to Rand at least? Is art an expression of certain ideals — ideals that transcend the medium by which they are expressed? If that's the case, I have no doubt many will agree with her. Many others will not. When we read a page of gorgeous, intricate prose, we are admiring the tool as much as the ideal: we're looking at the "how" as well as the "what". We feel — at least I do — that when the sentences go so well together that they form a few paragraphs of brilliance, we're seeing art manifest itself. It's not always about the rational underpinnings of the content. It's not always about using the hammer of language to build a cathedral to Mankind; sometimes we just want to see someone swing the hammer gracefully.

My book isn't even out yet and already I can't convincingly pretend I'm able to explain why I picked the words I did. And it's not a 645,000 word book. For Ayn Rand to suggest that Atlas Shrugged can be broken down to the level of punctuation is literally incredible: I do not believe it. It smacks of boasting, of course, but more crucially, it makes me think of factories, of cogs and wheels, of construction without artistic license. It suggests rigor but not vigor. The mundanity of her prose, the barely detectable development of her characters, the 60-page philosophical rant towards the end: all these things suggest that Rand was not actually interested in being an artist. The reason she gives us such a useless definition of literature is that she doesn't give a damn about literature.

Yet The Art of Fiction collects, without irony, her lectures on how to go about creating works of art with words. That's the mystery, and the greatness, of the whole thing. She definitely developed opinions on what art should be doing, but they contradict just about everything that makes literature important for most readers. Going through these lectures with a critical eye is a wonderfully frustrating experience. I disagree and get angry the entire way through, but the disagreement and the anger are educational.

It's like vegetables when you're a kid: even if they're raw and nobody really cares if you eat them, you should still taste them. You'll figure out why you like the cooked ones better.

About the author

Phil Jourdan is a writer, musician and distinctly unenlightened person. He is structural editor at Angry Robot, and a co-founder of Repeater Books and Litreactor. He splits his time between the UK and Argentina.