It’s fair to say Westworld is winning television right now. HBO’s latest gem and 2016’s best argument for reboot culture is being watched, discussed and dissected with far more fervor than expected for a show based on a 1973 film that is mostly remembered for Yul Brenner perfecting the iconic killer robot walk. But the story of an adventure park filled with lifelike robots just waiting to satisfy all of our darkest urges only gets more relevant as our technology makes immersive virtual worlds increasingly real and accessible, the premise becoming less fanciful with each passing year. Unsurprisingly, most of the coverage I’ve seen explores the influence of game design on the show, when it’s not wildly speculating about its many mysteries. No doubt Westworld is at its most fun at the intersection between the two, making the audience feel like a second player joining the party. However, the show gets pretty insightful on the writer, the act of creation, and the power of story as well.

That’s your cue to bail if you’re worried about SPOILERS.

The park and its army of artificial hosts are maintained by many different departments (QA, Behavior, Narrative) made up of the programmers, engineers and other personnel needed to keep it all running, providing a smooth experience for the guests. But just like everything in the park, nothing is simply what it appears to be. For the first half of the season, the presumably human characters we follow around on the staff all function as avatars for different kinds of writers and styles. Hotshot programmer Elsie Hughes is the young rookie writer, confident in her talent, always certain she’s the smartest one in the room. We see that she understands the hosts, or characters, better than most other humans, diagnosing behavioral problems that are misunderstood by other programmers and solving them with subtle fine-tuning. But she is also naive enough to assume that being smart is the same as being right, and even becomes enamored with one of her characters. We all like to think we’ve outgrown this bad habit, but every now and then we still struggle to cut that one perfect line or character that we really love, but just isn’t working as intended. It’s the best thing you’ve ever written, so it’s gotta fit somewhere, right? But if you tinker with your story too much just so you can squeeze your square peg into a round hole, you might end up breaking the whole thing. Sure, good characters have personalities and motives of their own, but the story should ultimately be under the writer’s control. Don’t let one of your creations, no matter how awesome, take your job.

Lee Sizemore, the effusively offensive Head of Narrative, is the shameless hack. He’s the only character on the show to be called a writer, and that word is always uttered with naked derision. Lee is the kind of writer that makes the rest of us look bad. Although, if we’re being honest, we’ve all been this guy at one point. College freshmen finishing their first fiction workshop, giggling maniacally as they type their “transgressive fiction,” nothing but vivid descriptions of every abhorrent act they had the courage to Google, convinced of their own brilliance. “Odyssey on Red River,” Sizemore’s latest narrative pitch, is a parade of groan-worthy attempts at edginess, like “self-cannibalism.” Watching Dr. Robert Ford, the park’s enigmatic creator, eviscerate Sizemore’s cheap appeals to the lowest common denominator might have been the most personally satisfying scene in the entire show. Much as we might hate to admit it, though, Lee kind of has a point. Literature is art, but it’s also entertainment. It’s great if the story can show the reader “who they could be,” but don’t get so high on pretension that you forget to have some fun. Even the most dour holocaust memoirs still have moments of levity.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is Theresa Cullen, the consummate cold and calculating professional who runs QA. She entertains no nonsense and will not tolerate Ford’s little flourishes when they interfere with park operations. When Lee Sizemore goes on one of his rants about the crimes committed against his artistic vision, Theresa punctures his ego and sends him back to work. She is the copywriter, the ruthless editor that will make you kill your darlings, that voice of reason we all know we should listen to more often. But no matter how good your editor is, it’s important to remember who’s writing the story. Your editor’s job (whether it’s another person or just a voice in your head) is to help you tell the best story you can, so listen to their advice, but like Robert Ford, you shouldn’t be afraid to stand up to them when you know you’re right. DON’T murder them, but if you have a particularly heated argument, just remember the history of literature is littered with fictional doppelgängers of editors meeting unspeakable ends.

Bernard Lowe, the head of the Programming Division, writes the code that brings Westworld to life, as well as improving and maintaining it. He is the studious academic, the literature professor or critic with a deep understanding of the craft of fiction. While he does not pen narratives or create characters himself, Bernard has mastered the techniques that make them more lifelike and believable. Whatever the creatives come up with, Bernard finds a way to improve upon it, so that each piece of the story is performing to its full potential. Given what we learn about Bernard near the end of the season, this makes even more sense. Any good writer should have more than a passing familiarity with these concepts, but it can also be helpful to have an outsider’s perspective. That’s why Dr. Ford keeps him around, despite Bernard’s unfortunate tendency to repeat himself. A fellow writer can examine your work with the dispassionate eye of a mechanic and tell you what parts aren’t working and what it will take to fix them.

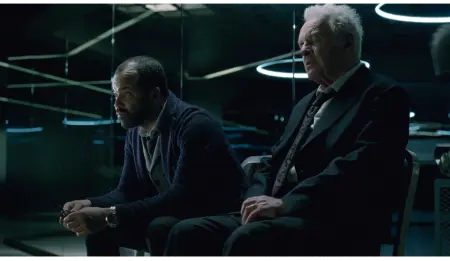

That brings us to the man himself, the charismatic and politely menacing Dr. Robert Ford. As the founder and chief visionary of the park, he enjoys unlimited creative freedom and godlike dominance over the inhabitants of Westworld, whether they be human or host. Ford is the eccentric genius we’d all like to believe we really are, the ultimate writer’s power fantasy. Everything he says sounds like it was written with a quill pen and he tells stories so enthralling that people have kept coming back for over thirty years. He creates characters so real they can pass for human and literally come to life. His intellectual property is so valuable that he can tell the Delos board to go screw itself, he’s gonna finish his story any way he pleases, and they cannot stop him. On our best days, we can feel like Dr. Ford: supremely confident and in control, impressing ourselves with our competence and command over the story. Many writers have at least one sublime scene, perfectly captured character or well-crafted world that makes them feel like a god, and keeps them writing in the hopes it can be repeated. While it’s certainly one of the perks of making up stories for a living, you don’t want to stray too far into wish fulfillment territory. The Man in Black, despite being the most dedicated player in Westworld, is bored with the transparent power fantasies of the park and bemoans the absence of a worthy adversary. Perhaps Wyatt and his band of masked raiders are Ford’s answer to him.

We have all been these writers at some point in our literary careers, and the best ones manage that miracle of balancing them all. The power struggle going on in the glass-walled boardrooms mirrors the internal struggle everyone faces when creating a new story. It’s important to remember that it isn’t a contest—you don’t want any of these voices to “win,” but to work together to create the most compelling fiction you can.

Which of Westworld's "writers" are you most like? Which do you wish you could do away with?

About the author

BH Shepherd is a writer and a DJ from Texas. He graduated from Skidmore College in 2005 with degrees in English and Demonology after writing a thesis about Doctor Doom. A hardcore sci-fi geek, noir junkie and comic book prophet, BH Shepherd has spent a lot of time studying things that don’t exist. He currently resides in Austin, where he is working on The Greatest Novel Ever.