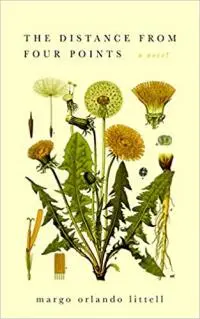

Photo courtesy of the author

In 2013, when I attended a prestigious writing conference, my workshop instructor’s reaction to my pages was a resounding “meh.” Not one to mince words, he told me the chapter I’d submitted wasn’t going anywhere—indeed, was going around in circles—and that the journey I’d imagined for my protagonist wasn’t an interesting journey at all. I had about a hundred pages of this novel back at home, and I came away from the conference convinced I should burn the whole manuscript. (I didn’t burn it. But I haven’t looked at it since.)

Instead of trying to rethink the plot or dive deeper into my characters, I decided instead to write something brand-new—something with a propulsive, commercial story. I’d always trafficked in quiet, character-driven fiction, and I took this unsuccessful workshop as a sign that it was time to shift course. I’d write something exciting, something page-turning, something with a lot of external conflict. There would be a shocking death. Ruthless antagonists. Deviant nuns. I’d set it in a small town—my preferred literary setting—but it would have a plot.

And so began the first iteration of what would ultimately become my novel The Distance from Four Points. The deviant nuns were my favorite part—they conspired to kidnap a teenager’s newborn, and one faked a pregnancy. A prosthetic pregnancy stomach called a Moonbump was involved. They weren’t the main characters, but they played a crucial role, even as the story otherwise began shifting. I let them run free. They were the craziest thing on the page. They popped up here and there, sometimes offering bits of wisdom, sometimes changing characters’ trajectories, sometimes providing a little macabre humor. The plot hinged on their machinations, and the silicon pregnant stomach. Because of them, I believed I had the plot-driven novel I’d been aiming for.

Meanwhile, the rest of the novel simmered. Robin, my protagonist, who loses her cushy suburban life and is forced back to her Appalachian hometown of Four Points, was changing her fundamental beliefs about home, friendship, and regret. Cindy, her BFF—a foul-mouthed secondary character who ran away with the novel after the very first scene I drafted her in—was wrestling with unexpected possibilities for redemption. The landlords making Four Points life difficult were fighting desperately for the status quo, their livelihoods at risk in a town hell-bent on transformation.

Meanwhile, the rest of the novel simmered. Robin, my protagonist, who loses her cushy suburban life and is forced back to her Appalachian hometown of Four Points, was changing her fundamental beliefs about home, friendship, and regret. Cindy, her BFF—a foul-mouthed secondary character who ran away with the novel after the very first scene I drafted her in—was wrestling with unexpected possibilities for redemption. The landlords making Four Points life difficult were fighting desperately for the status quo, their livelihoods at risk in a town hell-bent on transformation.

None of this had anything whatsoever to do with falsely pregnant nuns.

And yet: because the nuns were there, I felt able to play fast and loose with story and pacing. It was fun to write this way, nothing out of bounds; there was no limit but my imagination. I finished an entire draft. I revised extensively, the nuns still front and center.

Two years later, I went to another workshop, where the novel was warmly received. But during our discussion, my instructor waved her hand dismissively and said, “Of course, the nuns have to go.”

Of course. For the first time, I saw it clearly: they were part of a different story. I’d needed them to get over the seriousness of the literary, character-driven writing that had been suffocating me. I’d needed to write something a little strange, a little silly, a little fun—and, in doing so, I found my way to something real. The characters operating in the nuns’ shadow had found their voices, and it was time to clear the path for them.

So I killed my darlings. I rewrote the novel, leaving out the nuns. They’d been a kind of scaffolding, but it turns out my characters could support themselves as they navigated through their mistakes and reformations.

The nuns slinked into my DELETED SCENES file, and what emerged in their wake was a community in which Robin’s story could unfold. The nuns had been part of that community, but so were others who influenced Robin’s life more directly. There was Cindy, who ends up being a tenant in one of Robin’s apartments. There was Vincent, an old flame of Robin’s who threatens to pull her back into the darkest period of her life. There was Steph, a friend from Robin’s suburban life, who breaches the divide between Four Points and the rest of the world and shows Robin a new way to live. For many drafts, these characters had kept a low profile, simply responding to the nuns, moving about quietly beneath the dramatic surface of the story. Little did I know that they were the current sweeping Robin along.

No one journeys alone. Not in real life, and not in fiction. Focusing too intently on one character creates an insular echo chamber in which no real forward movement can happen, which I realized with my unsuccessful workshop piece. I set out to write a novel with both action and reaction, contemplation and collaboration, dreaming and doing. I overshot the mark with the nuns, but the intention was right.

This is not to say that every novel needs a clamoring supporting cast. For every Ducks, Newburyport, in which the unnamed narrator playfully free-associates for a thousand pages, there’s an Olive Kitteridge, whose title character comes to life not only in her own pivotal moments but through the demands made of her in other people’s stories. What links all types of novels, however, is a kind of opposition that fuels the paragraphs and pages. There may not be a grand deception on the magnitude of a Moonbump-wearing nun, but there is always an energetic foil that whittles an ordinary, static life into one of compelling evolution.

Every time I begin a new work, I face the risk of treading water, and over the years I’ve come to accept that this is what my early drafts are for. Sometimes the most pivotal characters need to be conjured and coddled into the story, under the shadow of misstarts and dead-end plotlines. They can be skittish, these characters. I’ve learned to welcome them in, even the ones who show up too early and stay too late. They’ll go, eventually, and the ones left behind will finally be able to sit down, relax, and really talk.

Buy The Distance From Four Points from Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Margo Orlando Littell grew up in a coal-mining town in southwestern Pennsylvania. She is the author of the Appalachian novels The Distance from Four Points and Each Vagabond by Name, which won the University of New Orleans Publishing Lab Prize and an IPPY Gold Medal. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in The New Guard, Embark: A Literary Journal for Novelists, Compose, Monkeybicycle, Real Pants, the Beloit Fiction Journal, and other places. She edits interviews for Newfound Journal, writes book reviews for the City Book Review, and lives in northern New Jersey.