I write it. I read it. I even have the lady balls (and grocery bills) to try and teach it. But what is It? Can you know It? Can you see It? And once seen, can It ever be unseen? Unknown?

It can be heartbreaking, as in Richard Thomas’s “Dance, Darling,” about twin holocaust survivors joined at the heart. Or It can be fantastical, as in Damien Angelica Walters’ new novel, Paper Tigers, about a broken bird of a girl who flies into a haunted photograph album so she can be whole again. Maybe. Or laced with surreal dread, as in Scott Nicolay’s “Eyes Exchange Bank,” a Ligotti-esqe journey to nightmare town. Or monstrous as in Livia Llewellyn’s “Engine of Desire.” Or all of the above like Stephen Graham Jones’s “Little Lambs,” about a haunted penitentiary that moves, imprisoning the watchers in the watch. All these stories instill a kind of terror in the reader, but the kind of terror where the fever dream is not so much to defeat It, as to see It, touch It. Make It stick. Because without It, what are we?

Weird horror has always had a tendency to gush, or dribble, to crawl or bubble from between the gaps of dark fiction, producing overlooked and uncatagorizable stories, the haunted, heartbreaking nature of which eludes definition. If horror suggests, within some margin of doubt that the monster is real, does The Weird take it just one step further and confirm to us that it is the margin itself, that penumbra of doubt that is the very destiny of our own homesick, lovesick soul?

Fucked if I know. So I decided to ask.

1. If the source of the terror in conventional horror is the monster—within or without—what do you think is different about weird horror? As a monster, should I be worried about this renaissance of the weird?

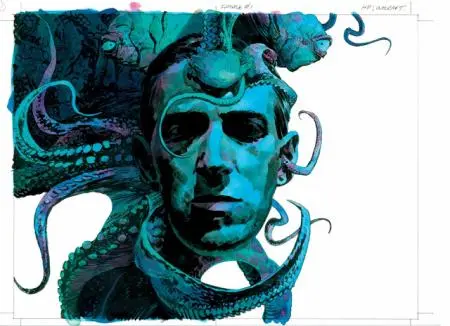

Stephen Graham Jones: I think weird fiction comes from uncertainty. As in, we don't know the scope or shape or depth of this reality we inhabit. But weird fiction, it's pulling back a curtain at the way back of the stage, and it's looking into that darkness . That, as it usually turns out, chittering darkness. That populated darkness. That hungry place. Look into a shadow long enough, you'll see a face, and then you'll judge what body should go with that face, and what story could produce a thing like that, and then you're in that story with it. You can drop the corner of that curtain down, scuttle back into the light, but the image is still in your head. The knowledge is still there, sending tentacles out inside your head. So, yeah, I do think monsters still play a part. Just, it's more like the basic monstrousness of existence. And how little we might finally matter in it all. It does come down to what's going to bite you and eat you, sure. But weird fiction also wonders Why is this happening?

Livia Llewellyn: I think the source of fear in a weird tale is when a protagonist in a “normal” (for them) situation and environment encounters something that is not part of their normal routine and/or world and/or world view. And I don’t necessarily mean a human protagonist—the question appears to assume that a monster might have no place in weird fiction, but who’s to say that a monster might not, in the course of its regular routines and life, happen upon a situation or place that would thrust them into their version of what's weird? That’s the beauty of “weird”—it’s not confined to the human experience. Cats get weirded out by cucumbers, apparently, and dogs can get weirded out by just about any kind of discomforting or unusual situation. I’m pretty certain I’ve weirded out my fair share of insects in my day. Weird is a particular state of being that combines the known with the unknown, and anything alive or undead can find themselves experiencing it.

Scott Nicolay: Monsters, Horror, and The Weird are all separate floating blobs in the multidimensional Venn diagram of literary darkness. I believe The Weird is something older and more profound than mere horror, although any human experience of The Weird is almost inherently horrific. Monsters crawl in and out of both horror and The Weird, but they too exist ultimately in their own protogonic state. The true monster is both singular and signatory, a showing forth, a sign, the progeny of some rupture in the fabric of reality.

The Weird derives from our attempt to grapple with an unreliable reality through the hooks and nets of literature, and the true monster signals the breakdown at some level of consensus reality, whether our shared understanding of the laws of physics or simply our place in the food chain, so the monster is often the horrific’s vector into The Weird. All three exist independently however, just as much as they often intersect, sometimes perfectly, as in John Carpenter’s The Thing, or “The Dunwich Horror.” The Weird Tale does not require a monster, but monsters are certainly at home in The Weird. And I do like to look at monsters.

Richard Thomas: I think it’s partly the fear of the unknown. You get a lot of that in Lovecraft, and with weird fiction, it’s usually something that is not the expected horror, but something outside the realm of traditional fear. It’s not the werewolf or vampire, but maybe a totally different mythology. It can be the same fear, what’s under the bed, but the reveal is usually stranger, more unexpected, more bizarre.

Damien Angelica Walters: I know many people have very concrete ideas of what weird fiction is versus horror. Say, tentacles versus werewolves. To me, weird fiction is about the strange in the everyday. A door in an apartment building leads elsewhere; a spectral figure appears; people say or do the unexpected and surreal. With horror, there's usually an explanation—the monster is hungry, the house is buried on a cemetery, the spectral figure is a murder victim's ghost—but with weird fiction, there's no concrete explanation. The strangeness simply is. But I know, too, that there are plenty of exceptions.

2. On a scale of 1 to 10, how scary does weird horror have to be, or would you agree with Caitlin R. Kiernan, that it’s complicated. That if horror is an emotion, no one emotion can, or should categorize weird fiction?

SGJ: I think any weird fiction story that doesn't at least try to fundamentally unsettle you, maybe even disturb you, then . . . I don't know. Maybe it's just, then, bad weird fiction? I don't want to kick stories and novels out of the clubhouse or anything. But, what I consider good weird fiction, it chews at whatever I've tethered myself to this world with. Too, that's what I like from anything I read, no matter the genre. If it doesn't change me, make me question things, then it's just ratifying what I already know. And I don't really need stories for that. Stories are meant to undermine. Weird fiction especially.

LL: Weird doesn’t have to be scary at all, or it can be unbelievably frightening—and I don’t think a scale is useful to measure “weirdness.” It really depends on the story and the storyteller. A number of Lovecraft’s stories are extremely weird, but in this day and age not considered truly scary. The movie “Beetlejuice” is weird, but not scary. You can walk down the streets of Manhattan and see a pantsless man wearing a rubber chicken head and think “okay, that’s weird” and not be scared at all—a bit unsettled maybe, but not scared! Weird is not horror, nor should its presence imply horror—it’s a style and/or a series of ideas or a particular setting that isn’t quite realistic in nature, that’s not considered “normal.” Horror and the attempt to scare a reader can be a part of that, or not.

SN: Given that I don’t see The Weird as a subset of horror but rather something more profound and entirely a priori to human experience, I don’t think it has to be anything at all. I believe it is inherently disturbing and often horrific, but it can be awesome in other ways, as in Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy, when Control encounters the doorway into Area X: “He didn’t expect it to be beautiful. It was beautiful.” An encounter with The Weird is more lasting than the effects of a horror film jump scare. Critic S.J. Bagley and others have spoken of a “literature of unsettlement,” and I think that arrow points a little closer to the truth. The scares can come anywhere along the scale, but they dig deeper and last longer when they’re weird.

RT: It’s complicated. 7? It doesn’t have to be scary, although I think two essential, defining components of it are terror (fear, anticipation, tension) and horror (disgust, shock, violence). It can be unsettling, or strange, it can be the acceptance of fate, or the revelation of something entirely different. There is quiet horror and so I imagine there can be quiet weird as well. Weird doesn’t have to be horrific at all, of course, it can be wondrous, and surreal, and even magical.

DAW: I don't know that scary is the word I'd use. I'd go with unsettling. But I've also read weird fiction that isn't even unsettling, just odd. So I'm in agreement with CRK.

3. Many of the readers of this article will be students of the craft. How important is setting, atmosphere, and style in your weird tales and can you offer any tips about how to keep horror weird?

SGJ: For me, weird fiction works best when we first get a few pages that establish the baseline 'normal.' A few pages that introduce both the character and the world, such that I can identify with the character and recognize this world as my world. That's how this story's going to disturb me. It's going to show me that what I thought was normal is, with a slightly closer inspection, actually pretty wicked and mean. This is also how horror starts. Where The Weird and horror diverge, though, it's that horror's kind of conservative, in that it's always fighting tooth and nail to get back to the normal, it always wants to do whatever it has to to re-establish the status quo, the good old days before this intrusion of wrongness. Weird fiction, it's more about, now I've seen how it really is, existence. That dark, vast underbelly. Can I now go back to just being a mite between the scales? Is there any way I can forget about this? Weird fiction doesn't want to change things back to how they were. The characters in weird fiction, when they survive, they just want to forget, please. Horror fights the bear, and wins or loses. The weird has to live in a world where there's bears everywhere, now. And they're watching you.

SGJ: For me, weird fiction works best when we first get a few pages that establish the baseline 'normal.' A few pages that introduce both the character and the world, such that I can identify with the character and recognize this world as my world. That's how this story's going to disturb me. It's going to show me that what I thought was normal is, with a slightly closer inspection, actually pretty wicked and mean. This is also how horror starts. Where The Weird and horror diverge, though, it's that horror's kind of conservative, in that it's always fighting tooth and nail to get back to the normal, it always wants to do whatever it has to to re-establish the status quo, the good old days before this intrusion of wrongness. Weird fiction, it's more about, now I've seen how it really is, existence. That dark, vast underbelly. Can I now go back to just being a mite between the scales? Is there any way I can forget about this? Weird fiction doesn't want to change things back to how they were. The characters in weird fiction, when they survive, they just want to forget, please. Horror fights the bear, and wins or loses. The weird has to live in a world where there's bears everywhere, now. And they're watching you.

LL: I think atmosphere and setting is paramount in a weird tale, because so much of the emotion of “weirdness” is derived from something being not-ordinary or “off” in the world of the protagonist. It’s important to therefore create that world through description, detail, senses, culture, routines, as much as possible in order to show how the weirdness comes to inhabit or infect or change it. I think probably the biggest danger in writing that type of tale, however, is keeping it consistent throughout the entire story. I know that in my writing, as I get closer to the end, I tend to rush the words and drop a lot of the details and world-building that shapes the first half of the story. I get sloppy—it’s a common mistake. I think once a writer has finished their piece, it’s important to go back and make sure they haven’t neglected the atmosphere and details in the last half of the story (or novel) for the sake of wrapping up the plot. Weird isn’t an emotion, it’s a condition or changing condition that the protagonist reacts to (physically, intellectually, and emotionally), and as the writer it’s vital for me to make sure that the reader is fully immersed in and fully believes the reality of the world and subsequently the reality of the weirdness that pierces that particular world.

SN: In my personal rubric for writing The Weird, I ascribe primary importance to both place and atmosphere: “Place is essential. Setting must be as well-developed as any other element of the tale” and “Atmosphere must be as well-developed as any other element of the tale.”

I don’t believe in any hard and fast rules for approaching The Weird through fiction, but these elements are essentials in the path which interests me at present. I employ real locations as much as possible and scout them whenever I can. I know I am not alone in this. Barron, Kiernan, and VanderMeer all have done it. Blackwood, Klein, and Lovecraft did it. Mary Shelley did it, as my friend Selena Chambers so sublimely proved by retracing her steps—and her monster’s.

Dread is the default setting for atmosphere in The Weird. Bring it, ratchet it up, maintain it. I don’t agree with Lovecraft on much, but he did understand what makes a story weird, which is why he identified Blackwood’s “The Willows” as the ur-Weird Tale—and why he ripped off its atmosphere-before-plot intro technique for two of his best stories: “The Dunwich Horror” and “The Colour Out of Space.”

If you really want to go to school for building atmospheric dread, study William Hope Hodgson, who could sustain it at lengths and levels Lovecraft never dreamed of. Hodgson’s novels The Night Land, The Boats of the Glen Carrig, and The House on the Borderland are unsurpassed masterpieces of long-game dread. See also Jean Ray’s Malpertuis, or his brilliant novellas “La Ruelle ténébreuse” and “Le Psautier de Mayence” (both are done justice in Lowell Bair’s translations, which appear in the VanderMeers' phone book of an antho, The Weird)

RT: I think it’s very important. It’s another crucial part of horror in general, so if you’re going to go weird (surreal, strange, unexpected, absurd) you better ground it in some sort of base reality before you take it someplace different. Or, if you’re going to start it someplace weird, from the first sentence, do the work to establish that world, so that it makes sense, and is believable, in all of its strangeness and disorientation. Weird fiction works especially with sensory depth and a layered setting, I think.

4. Some writers have suggested that motivation, or lack of it, is key to weird horror, that unlike more conventional horror, part of the source of the disturbance, is the undecidability of what a character wants. Would you agree that an inexpressible emotional logic is the engine driving weird horror/fantasy and where does your work fit in?

SGJ: Your character of course has to want something, has to be willing to trade it all in for that something. Story happens when there's obstacles to achieving that desire. Plot comes from the decisions and resultant actions the character makes, working towards that goal. Just basic story mechanics. With weird fiction, though, man, nine out of ten times, what gets the character in trouble is their own stupid curiosity, right? They open the book, they look behind the shelf, they walk into the dark part of the woods, whatever. Which, we can call that mysterious, why they do it, but, to me, the reason they do it, it's simply that they're human. They're expressing the trait that's discovered us fire, and the wheel, and projectile weapons, and everything since: curiosity. We're a species that looks under rocks, when it would have been perfectly fine for us to keep on walking by. But sometimes that instinct, it burns us. Sometimes our human curiosity, it brings us face to face with a vastness we can't begin to comprehend. That's kind of the magic of weird fiction, I think. It's using our saving, maybe defining trait against us. In order to survive, we have to stop being human, basically. We have to cash out what we are in hopes of some version of what we used to be just walking on by that rock, into the future. Which is a bad trade. But, looking under that rock, it's no guarantee of happiness either.

SGJ: Your character of course has to want something, has to be willing to trade it all in for that something. Story happens when there's obstacles to achieving that desire. Plot comes from the decisions and resultant actions the character makes, working towards that goal. Just basic story mechanics. With weird fiction, though, man, nine out of ten times, what gets the character in trouble is their own stupid curiosity, right? They open the book, they look behind the shelf, they walk into the dark part of the woods, whatever. Which, we can call that mysterious, why they do it, but, to me, the reason they do it, it's simply that they're human. They're expressing the trait that's discovered us fire, and the wheel, and projectile weapons, and everything since: curiosity. We're a species that looks under rocks, when it would have been perfectly fine for us to keep on walking by. But sometimes that instinct, it burns us. Sometimes our human curiosity, it brings us face to face with a vastness we can't begin to comprehend. That's kind of the magic of weird fiction, I think. It's using our saving, maybe defining trait against us. In order to survive, we have to stop being human, basically. We have to cash out what we are in hopes of some version of what we used to be just walking on by that rock, into the future. Which is a bad trade. But, looking under that rock, it's no guarantee of happiness either.

LL: It’s entirely possible to have a stupendously weird story where people know what their world is about and can acknowledge the weird and different circumstances that have entered it and go about trying to solve it with minimal waffling and journaling—see China Mieville’s novel Perdido Street Station for an entire novel about strange humans and creatures in a strange city trying to battle weirdness with (for their world) logical magic and science, but while also dealing with their own very ordinary problems and relationships and circumstances. Weirdness may happen, but sometimes you still have to stop and eat a sandwich and pay some bills. If there’s any hesitation in the face of weirdness, it’s a natural reaction—fight or flight, most likely—but it’s not necessary to make hesitation the entire character arc or plot. That only really worked in “Hamlet,” and even then only as a ruse while he plotted retribution and revenge.

BTW, I have no idea where my work fits in with any of these definitions of weird. My characters tend to confront something weird, and then embrace it or fight it by becoming even more weird and monstrous than the thing they’re fighting. I don’t know what that means—but I think authors (and all artists in general) shouldn’t be the ones trying to assign a place within specific genres and traditions for their creation. That’s best left to readers and reviewers and academics.

SN: I must not have been at that con because I have never encountered this suggestion before. The question depends on several preconditions, none of which I subscribe to in full. That said, I think characterization is as important to good Weird Fiction as are atmosphere and setting, and that awareness is an essential difference between the authors of the Farnsworth Wright era Weird Tales Circle and key figures of the current Weird Renaissance. Look at contemporary writers such as Nathan Ballingrud, Livia Llewellyn, Usman Tanveer Malik, Robert Levy, or Alistair Rennie for a few quick and excellent examples.

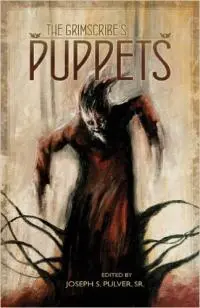

Laird Barron pointed out a few years back that almost every Ligotti story has the same protagonist: a white male in his twenties or thirties, overeducated, underemployed, and usually unattached. And that guy has been around since Poe. My story “Eyes Exchange Bank” in Joe Pulver’s Ligotti tribute anthology The Grimscribe’s Puppets was an attempt to explore what that guy would be like as a real person, based on experiences I remembered from back in the Eighties when I was that guy.

I have found you can drive a story through atmosphere and character, rather than directly through plot. Plot is always artificial, while atmosphere and character are organic. Plot will arise naturally from those elements if allowed time to develop, which is why the novella is often an ideal form for The Weird.

RT: I think there is always a sense of discovery, yes. There is that unknown. With classic horror the results are often expected right? It’s a demon, a ghost, a werewolf, a zombie, a vampire. With The Weird, it’s rarely what you are anticipating—it’s much worse, much stranger, so it’s hard to react, as a character. There is no silver bullet, no wooden stake. It’s something beyond comprehension.

I also agree that in weird fiction the motivation, the emotion, can be more visceral, but that can also be there in your standard horror story, other speculative fiction. What New-Weird and Neo-Noir may have in common, the genre-bending and hybrid fiction that I’m most interested in reading and writing these days, is that it takes the standard narrative to new places—different monsters, different storylines and plots, different settings, and different conflicts. I think that’s true of a lot of contemporary dark fiction.

I don’t know how much of my work would be classified as weird. I do a lot of horror, yes, and neo-noir, as well as fantasy and science fiction, but quite often my writing is some blend of those genres, plus maybe some transgressive, and/or magical realism. I’m sure there is some of my work that may fall into The Weird category. I wrote a story called “White Picket Fences” (Shadows Over Main Street) that was, for most of the story, a 1950s Lovecraftian horror story, fairly traditional, but at the end the great unknown, the cosmic horror unfurls with some fairly strange and horrific results. Maybe “Flowers for Jessica” (Weird Fiction Review, see it’s right there in the title) which chronicles a woman dying of a broken heart then slowing coming back to life. Those might qualify.

DAW: I'm not even sure that my work does fit, to be honest. My focus in stories is typically an emotional core. I've joked more than once that I like it when my work makes people cry, but it isn't really a joke at all.

5. Okay, finally. Story. What is one of the most unsettling weird stories you’ve read recently, and what was it about the story itself that stuck?

SGJ: Talking just stories, that'd be from Karen Runge's "Seven Sins." Just all of them, but probably most sticky in my head is the mom-son one. I forget the title. But, don't read that one if you want to keep on being happy. Also, Brian Evenson's "Click" from A Collapse of Horses got under my skin in a not-great, pretty wonderful way. Third—let's pretend you gave me three slots to fill?—I just finally, years after the rest of the world, got around to David Foster Wallace's "Good Old Neon" from, I think, Oblivion. I stopped reading his stories at Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, as I thought that was kind of a cutesy collection. With Oblivion, though, it looks like he was back in top form. That "Good Old Neon" story, I doubt anyone else would categorize it as weird. But it has fundamentally unmoored me, and kind of infected me. In the best way. I wouldn't trade having read it. And neither am I sure I want it in my head. If that's not weird, then sign me up for whatever it is.

LL: I recently read the Korean novella The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith. It is one of the most spectacular and disturbing works of weird fiction I’ve encountered in a long time, and I can’t recommend it enough. I’m not going to spoil it, I’m only going to say that it starts out as a very ordinary story about a middle-aged woman who decides, against the wishes of her husband and family, to become a vegetarian. There are no demons or gods or monsters. It’s not supernatural. It takes place in the “real” world with “normal” people, who make ordinary choices and then: WEIRD SHIT happens.

SN: I don’t read near as enough as I want to anymore, and I don’t even come close to keeping up with all the great weird fiction coming out. That said, “The Fisher Queen,” by Alyssa Wong. I interviewed her recently for my podcast, The Outer Dark. Or “Scarecrow” by Alyssa Wong. Or “Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers,” by Alyssa Wong. Anything by Alyssa Wong. Alyssa Wong is a monster. There are lots of great monsters out there right now. It’s a great time to be weird.

RT: Oh, man, that’s tough. The one that popped into my head was “The Familiars” which I reprinted in The New Black. I discovered it in The Weird, edited by Jeff and Ann VanderMeer. It’s written by Micaela Morrissette, and is about a boy with a childhood friend that turns out to be something else entirely, the thing under the bed turning out to be pretty strange and horrific. I’ll go with that one. It’s very unsettling, and yet, touching as well. I like that mix of sweet and sour. Felt the same way about “Father, Son, Holy Rabbit” by Stephen Graham Jones, and “Windeye” by Brian Evenson, and “Wilderness” by Letitia Trent.

DAW: I recently reread "Wilderness" by Letitia Trent. What stuck for me is the setting. I don't want to give anything away, but it's about someone in a very ordinary place and then things become not quite so ordinary.

About the author

J.S. Breukelaar is the Shirley Jackson Award nominated author of Collision: Stories, and a finalist for the Aurealis, Ladies of Horror Fiction (LOHF), and Australian Shadows Awards. Her previous novels are Aletheia (an Aurealis Award nominee), and American Monster (Wonderland Award Finalist). She has published stories, poems and essays in publications such as Black Static, Gamut, Unnerving, Lightspeed, Fantasy Magazine, Lamplight, Juked, and others including Women Writing the Weird, Tiny Nightmares and Years Best Horror and Fantasy, 2019. Her new novel, The Bridge, will be released in early 2021, as well as Turning of the Seasons, a collaborative flash fiction collection with Sebastien Doubinsky. A columnist and regular instructor of Weird Writing at LitReactor.com, she has a PhD in Creative Writing and Film studies and lives in Sydney, Australia where she teaches at the University of Western Sydney, and in the University of Sydney extension programs. You can also find her at www.thelivingsuitcase.com and twitter.com/jsbreukelaar.