Most people know Walter Mosley, who turns 71 years old this week, from his detective novels, including the famous Easy Rawlins series which began with Devil in a Blue Dress. But Mosley is much more than a mystery writer. He’s written sci-fi, essays, and literary fiction, though none of that is as well-known as his mystery work.

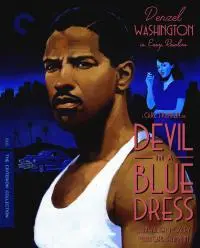

Like most other people, I always associated Mosley with sleuths and thrillers, and the film of Devil in A Blue Dress starring Denzel Washington. Since I’m not a huge mystery reader, I didn’t think to explore Mosley’s writing, but then I heard someone speak on a trilogy of his books about an ex-con that apparently had superb renderings of natural spoken language. That kind of thing intrigues me more than a whodunit, so I picked up the books.

Having ripped through them this past fall, let me tell you that these books need to be more widely read. There’s so much in them for avid readers, and for writers as well.

The trilogy centers on Socrates Fortlow, an ex-con guilty of rape and double murder who’s trying to make his way in the Watts neighborhood of LA. Through the books, Fortlow creates connections in his community, tries to make an honest living, never denies his guilt, and consistently explores what it means to live a good and righteous life.

The first two books, Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned and Walkin’ The Dog, are collections of interconnected short stories. The third, The Right Mistake, is called a novel, but I’d say it’s another collection. What’s more important than the books’ structures is Mosley’s ability to render natural spoken English, and how he uses it to produce effects, especially empathy.

Anyone who’s written knows that getting natural English across on the page is difficult. It doesn’t seem like it should be since we speak and hear this language every day, but talking and writing are, of course, very different things. Young writers I’ve seen lean too heavily on tricks like phonetic spelling (“wanna” instead of “want to”) or italics to show emphasis. Those approaches aren’t incorrect, but they’re not the most effective ones either.

Mosley’s writing is a masterclass in utilizing syntax and context to show everyday English, with just a sprinkling of those other techniques when they’re truly necessary.

You could pick a page at random in any of these three books and find a good example of natural English spoken by one or more of the characters. Here are a few I like, just to illustrate the point:

“Shit. Cops could come in here an’ blow my head off too, but you think I should kiss they ass?”

That’s from Always Outnumbered. There’s a small bit of phonetic dialect, yes, but most of the way Mosley renders his natural English is with syntax. Compared to, shall we say for lack of a better term, the King’s English (I don’t like the term “standard English” since I don’t think such a thing actually exists), Mosley shows how everyday English speakers sometimes drop articles and possessives. He’s clearly representing an African American syntax, and doing so in a way that allows readers to fall into it, to hear it as they read. Some people might think phonetic spellings would be a clearer guide, but in fact it’s syntax that does the job.

Here’s another example, this from Walkin’ The Dog:

“I never bled for nobody didn’t bleed for me.”

Again, the natural English is clear to the readers through the use of syntax. In this case Mosely uses only the arrangements and choices of words to gain this effect, and I don’t think there’s anyone out there who won’t read it just the way he wants them to.

While the first two books are excellent portrayals of natural English, especially the English of urban African American communities, it’s in the third installment, The Right Mistake, that Mosley makes further use of natural language, and to even greater effect.

Here’s an example that’s a little subtler, but no less effective.

“You smoke?” Socrates asked.

“I have one every day,” the small man said, looking up, smiling. “Benson and Hedges. My wife tells me it will kill me and I tell her that she will kill me with her worries.”

The small man in question is Chaim Zetel, an older, Jewish character who befriends Socrates Fortlow. There’s lots of interesting ground to explore here, especially since Mosley is half black and half Jewish, but I’ll stick to the language.

The small man in question is Chaim Zetel, an older, Jewish character who befriends Socrates Fortlow. There’s lots of interesting ground to explore here, especially since Mosley is half black and half Jewish, but I’ll stick to the language.

The Right Mistake shows Mosley’s range of representing the different types of everyday English. He’s excellent as ever when it comes to types of African American English, but Zetel shows more of the author’s skill. The simple lack of contractions helps to show the character’s age, and the straight-forward word choices shows that he’s a down to earth person. The syntax, of course, shows that he has a different background than Socrates Fortlow, which is the point.

The way Walter Mosley writes his characters’ English is not only technically masterful, it helps to evoke empathy in the reader. This is especially true in The Right Mistake where part of the story involves Socrates Fortlow getting possession of a small house which he uses to host various meetings, including what comes to be known as the Thinkers’ Club. The Thinkers are people of different races, economic status, and religions, and Mosley lets us connect with them in part through the different English they bring to their meetings.

There's plenty of research showing that exposure to foreign languages helps develop empathy in a person. While understanding a different vernacular isn’t the same as learning a foreign language, the principle seems to hold. Understanding the nuances of how people communicate aids with a deep comprehension of the people themselves.

In The Right Mistake, the readers and characters go on the same journey—listening to different people speak the same language in their own ways, and developing deeper understandings of one another in the process.

These books, especially the third one, felt almost Pollyanna-like when I read them in 2022. The Right Mistakecame out in 2008, a time of less polarization and disagreement-for-sport than we experience now. Something like The Thinkers’ Club felt more possible back then.

But fifteen years later, though the world has changed, Mosley’s idea remains valid.

Everyday language is a way to understand different kinds of people. Diving in to those differences is vital. I’m not saying it’s going to solve all the country’s ills, but it’s a good first step to understanding the people who probably live a stone’s throw from you. And Mosely, the master, shows us the way.

Get Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned at Bookshop or Amazon

Get Walkin’ The Dog at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Right Mistake at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Joshua Isard is the author of a novel, Conquistador of the Useless (Cinco Puntos Press), and his stories have appeared in numerous journals including The Broadkill Review, New Pop Lit, and Cleaver. He studied at Temple University, The University of Edinburgh, and University College London.

Joshua directs Arcadia University’s MFA Program in Creative Writing, and lives in the Philadelphia area with his wife, two children, and two cats.