Header image via Pixabay

In case you were wondering (but you probably weren’t), it’s possible to purchase a Bible that is one nanometer (nm) large—that is one billionth, or 10 to the ninth power, of a meter, the comparative size of a marble to Earth. This Bible can only be read with an electron microscope (can you imagined being hired to proofread that?). As it turns out, however, it still may not technically be the world’s smallest “book,” a title for which there is a surprisingly wide field of competitors, as it’s made from a silicon wafer.

Welcome to Turnip Town

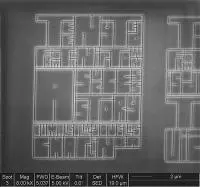

If you try to find a direct answer to the query, “What is the world’s smallest book?” you’ll quickly realize that it depends on exactly how you frame the question, and what exactly you consider a "book." The Guinness World Records website currently lists Teeny Ted from Turnip Town written by Malcolm Douglas Chaplin and published by Robert Chaplin as the smallest reproduction of a printed book, which cost $15,000 to make and is a micro-tablet book carved on pure crystalline silicon pages. The book was etched using an ion beam at Simon Fraser University in Canada and measures 70 by 100 micrometers (mm).

If you try to find a direct answer to the query, “What is the world’s smallest book?” you’ll quickly realize that it depends on exactly how you frame the question, and what exactly you consider a "book." The Guinness World Records website currently lists Teeny Ted from Turnip Town written by Malcolm Douglas Chaplin and published by Robert Chaplin as the smallest reproduction of a printed book, which cost $15,000 to make and is a micro-tablet book carved on pure crystalline silicon pages. The book was etched using an ion beam at Simon Fraser University in Canada and measures 70 by 100 micrometers (mm).

In 2016, Vladimir M. Aniskin, a so-called "micro-miniaturist" from the city of Novosibirsk, created a micro-book by hand with pages that measured 70 by 90 mm or 0.07 by 0.09 millimeters in a bid to unseat this record (it’s not fully clear if he was successful in this). Bear in mind, the terms on the Guinness website are “smallest reproduction of a printed book.”

The smallest letterpress book, on the other hand, is the Glennifer Press 1978 edition of Three Blind Mice. At 2.1 mm in height, the nursery rhyme was printed on pages of fine white paper which had been cut to size with a scalpel. Dental tweezers were employed to glue the eight leaves to the case. Old King Cole is the smallest book using offset lithography and the smallest in the Library of Congress.

A Volume the Size of a Fingernail

All right, so there’s quite a few aggressively tiny books out there. But...why? According to The Art of Small Things by John Mack, the competition to create the world’s smallest book has been pursued since at least the seventeenth century. Bloem-Hofje, a bound copy of a Dutch poem by C. van Langeby, was created in 1674 by Benedikt Smidt and, at roughly the size of a fingernail, remained the smallest book known for two centuries. The volume was "gilt-tooled on red leather and with a miniscule and finely chased gold clasp." Its original purpose was to prove how skillful its creator was, and to hopefully win him new business following a move to Amsterdam. It was unseated by a version of Galileo a Madama Cristina di Lorena, which measured only 1.9 by 1.3 cm. At the time The Art of Small Things was published, the Guinness Book of Records listed Anatoly Konenko’s printing of Anton Chekov’s Chameleon as the title holder for world’s smallest.

But Really, Why?

The Miniature Book Society acknowledges the difficulty in reading these books, stating that “craft miniature books need only satisfy the maker.“ But are there other reasons for creating a literary work on a microscopic scale, and is there a future for books and nanotechnology? The nano Bible mentioned above, for instance, functions as part of a piece of jewelry. It’s hardly a readable copy (especially since it’s in ancient Greek), but it is portable. There are a few niche reasons why one might want to confine a book to such a small scale; hiding information that is only meant to be seen by someone who knows where to look, perhaps, or for novelty. Miniature books on deportment were easy to stow around the home for quick reference. In The History of the Book in 100 Books: The Complete Story, From Egypt to e-book, authors Roderik Cave and Sara Ayad state that miniature versions of the Koran issued with a magnifying glass and metal locket were popular with Muslim soldiers who served in the Indian army during World War I. Not to mention that tiny things are just kind of fun. Who wouldn't want a library that fits in a walnut shell? If not to read, at least to tell people about at parties or on Instagram. But will nanotechnology revolutionize the publishing industry by driving sales of novels that can only be read by a scanning electron microscope? The odds seem very small.

The Miniature Book Society acknowledges the difficulty in reading these books, stating that “craft miniature books need only satisfy the maker.“ But are there other reasons for creating a literary work on a microscopic scale, and is there a future for books and nanotechnology? The nano Bible mentioned above, for instance, functions as part of a piece of jewelry. It’s hardly a readable copy (especially since it’s in ancient Greek), but it is portable. There are a few niche reasons why one might want to confine a book to such a small scale; hiding information that is only meant to be seen by someone who knows where to look, perhaps, or for novelty. Miniature books on deportment were easy to stow around the home for quick reference. In The History of the Book in 100 Books: The Complete Story, From Egypt to e-book, authors Roderik Cave and Sara Ayad state that miniature versions of the Koran issued with a magnifying glass and metal locket were popular with Muslim soldiers who served in the Indian army during World War I. Not to mention that tiny things are just kind of fun. Who wouldn't want a library that fits in a walnut shell? If not to read, at least to tell people about at parties or on Instagram. But will nanotechnology revolutionize the publishing industry by driving sales of novels that can only be read by a scanning electron microscope? The odds seem very small.

Could you see a hobby in collecting miniature books? Perhaps you’ll break a record of your own and challenge Sathar Adhoor for his Guinness record of the largest collection of over 3,000 miniature books.

Get The Art of Small Things at Amazon

Get The History of the Book in 100 Books at Bookshop or Amazon

Inserted image of Teeny Ted From Turnip Town by Simon Fraser University

Looking for Christian editing jobs? Check this article out.

About the author

Leah Dearborn is a Boston-based writer with a bachelor’s degree in journalism and a master’s degree in international relations from UMass Boston. She started writing for LitReactor in 2013 while paying her way through journalism school and hopping between bookstore jobs (R.I.P. Borders). In the years since, she’s written articles about everything from colonial poisoning plots to city council plans for using owls as pest control. If it’s a little strange, she’s probably interested.