What with the release of the film Trumbo on November 6 and the upcoming Day of the Imprisoned Writer on November 15, it's the season of persecution as far as writers are concerned. I'm not talking about self-persecution — the nasty little voices inside us who remind us that we're essentially worthless, talentless hacks. No, I'm referring to the jackboot kind of persecution — the type that involves shackles and handcuffs, judges' gavels pounding and cell doors clanking shut. The hopeless type. The kind that strikes terror in the hearts of writers living under repressive regimes. The type that's meant to keep us silent.

Here are only a few of the thousands upon thousands of writers who have paid a steep price for self-expression. They put my own complaints (The internet is slow! My editor changed a word without asking me! I can't write when the neighbor's dog is barking!) to shame.

![]() Dalton Trumbo and the “Unfriendly 10”

Dalton Trumbo and the “Unfriendly 10”

In 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) subpoenaed a number of Hollywood screenwriters, directors, actors, and others to testify about what they knew about Tinseltown’s infiltration by dastardly communists. People tend to associate HUAC with Joseph McCarthy, but McCarthy was a senator, not a member of the House. No matter. HUAC made it perfectly clear that the House could be every bit as fascistic as the Senate.

Ten writers and directors refused to cooperate with HUAC. Found to be in contempt of Congress and sent to prison, they were: Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Alvah Bessie, Edward Dmytryk, John Howard Lawson, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, Albert Maltz, Herbert Biberman, and Ring Lardner, Jr. They were the subjects of one of Billy Wilder’s most widely quoted quips: “Of the Unfriendly 10, only two had any talent; the other 8 were just unfriendly.” “Blacklist, schmacklist,” Wilder also said – “as long as they’re all working.” (To my knowledge, Wilder never publicly named the two with talent.)

Dmytryk fled to England but returned when his passport expired. After a few months of imprisonment, Dmytryk’s careerism took the place his conscience had once occupied and he ratted out his former friends. The studio bosses swiftly deemed him rehabilitated, and the producer Stanley Kramer hired him to direct The Caine Mutiny.

Trumbo and Lardner were the most successful of the non-sellouts. Before HUAC, Lardner wrote Woman of the Year for Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn as well as an uncredited rewrite of Laura. Trumbo had written Kitty Foyle and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. While blacklisted, he wrote Roman Holiday and the great Gun Crazy under assumed names. In 1960, Otto Preminger announced that Trumbo had written the script for Exodus, and Kirk Douglas went public with the news that Trumbo had written Spartacus. These revelations effectively marked the end of the blacklist era.

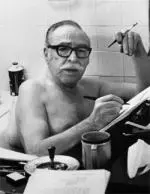

![]() Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

One of the wittiest people who ever lived — and he lived large — Oscar Wilde wrote marvelous plays (The Importance of Being Earnest, Lady Windermere’s Fan, and others), a terrific novel (The Picture of Dorian Gray), a long and famously bitter letter (De Profundis), and an epic poem (The Ballad of Reading Gaol). His torment began when the Marquess of Queensbury left a calling card for Wilde at Wilde’s gentlemen’s club; the card read, “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite.” That’s right. The fuckwad couldn’t even spell it correctly. Despite the fact that Queensbury was right — not only was Wilde in love with Queensbury’s son, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, he had also grown fond of picking up studly street boys — Wilde made the disastrous decision to sue Queensbury for libel. He apparently thought that his wit would triumph. He was quite wrong. When defense counsel asked Wilde on the stand whether or not he had ever kissed a certain youth, Wilde flippantly answered, “Oh dear, no! He was a particularly plain boy — unfortunately ugly.” From that moment on Wilde’s life was hell.

It was Bosie, not Wilde, who memorably described gay attraction as “the love that dare not speak its name.” Nowadays, when the love that once dared not speak its name just won’t shut up, it may be difficult to appreciate the depth to which Wilde sank when the name got spoken in court. He was forced to pay Queensbury’s legal costs, which left him bankrupt. He was then charged with “gross indecency” (a catch-all term that described essentially every homosexual act except butt fucking, which the word sodomy so biblically defined.) He was thrown in prison and put to hard labor. After his release he applied for a six-month religious retreat, but even the Jesuits wouldn’t have him. He moved to Paris and lived in a squalid hotel room, about which he said, “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go.” The wallpaper won; Wilde died at the age of 46. Lord Darlington in Lady Windermere’s Fan might well have been speaking for Wilde himself — and for many of us — when he declares, “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

![]() Jason Rezaian

Jason Rezaian

A reporter and Tehran bureau chief for the Washington Post, Jason Rezaian was thrown in an Iranian prison in July, 2014, on charges of espionage and writing “propaganda against the establishment,” a goal to which those of us who do not live under tyrannical religious fanatics often aspire. Rezaian has now been imprisoned for almost sixteen months. During the first nine months, the charges against him were not even made public. His trial began in May of this year and was conducted in secret. Iranian television announced the verdict last month. No big shock, the kangaroo court found him guilty.

Dana Milbank, Rezaian’s colleague at the Washington Post, describes as “baffling” the Obama Administration’s quietude on the subject. “Where was the demand that Iran immediately release Rezaian and the two or three other Americans it is effectively holding hostage?” Milbank raged. “Where was the threat of consequences if Tehran refused? How about some righteous outrage condemning Iran for locking up an American journalist for doing his job? Even if his outrage came to nothing, it would be salutary to hear the president defend the core American value of free speech.” Indeed.

Unfortunately, there's not much we can do to support Jason Rezaian. Signing an online petition is just about all there is. So do it. Now.

![]() Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Best known for her powerful, rabble-rousing speeches, Emma Goldman was also a prolific writer of books and pamphlets. A committed anarchist, Goldman made herself a continuing thorn in the American justice system’s side. After delivering a rousing speech before a crowd of 3,000 in New York City’s Union Square, Goldman was arrested, charged with “inciting to riot,” found guilty, and thrown in jail. A few years later, Leon Czolgosz — he was an anarchist, too, only he was crazy — shot President William McKinley to death and told the authorities that he had been influenced by Goldman. This did not help Goldman. Nevertheless, she rose to Czolgosz’s defense, a stance that, predictably, did not help her either. She went on to start a radical journal, Mother Earth; to become a close ally of Margaret Sanger, who coined the term “birth control” and advocated its use; to be arrested and jailed for showing a crowd how to use contraceptives; and eventually to be deported to Russia, where she had been born.

Goldman soon became disillusioned with the by-then-Soviet Russia, moved to Berlin, and wrote articles for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. These essays were then published as books under the titles My Disillusionment with Russia and the even more creative My Further Disillusionment with Russia, both of which she protested to no avail.

Later, she made no new friends when she refused to support England and France in the run up to WWII, writing, "Much as I loathe Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin and Franco, I would not support a war against them and for the democracies which, in the last analysis, are only Fascist in disguise.” She died in Toronto in 1940.

![]() Osip Mandelstam

Osip Mandelstam

One of the most horrific examples of writers who put their lives on the line for their writing, Osip Mandelstam was a Polish Jew whose family moved from Warsaw to St. Petersburg when Osip was still an infant. He published his first book of poems, The Stone, at the age of 22. In 1933, at age 42, he had the courage to read to a few friends a harsh little poem he’d written about Josef Stalin. Here are a few choice lines:

His cockroach whiskers leer

And his boot tops gleam.

Around him a rabble of thin-necked leaders—

fawning half-men for him to play with.

Six months later he and his wife, Nadezhda, were exiled to a small town in the Ural Mountains. This relocation was only the beginning of his suffering. The “Great Purge” began in 1936, and it wasn’t long before Mandelstam was arrested and charged with “counter-revolutionary activities,” convicted, and sentenced to five years at what the Soviets euphemistically called a “correction camp.” He was sent to Vladivostok, which is on the Sea of Japan near the border with Korea — in other words, as far away from Moscow as one can get and still be in Russia. He died there in 1938 at the age of 47.

Osip Mandelstam was fully rehabilitated 49 years later under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost (openness). A fat lot of good it did him. Mandelstam himself took an ironic view of his horrifying writer’s life: “Only in Russia is poetry respected; it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?”

So the next time you complain about running out of toner, or the fact that your local coffee joint makes you buy something in order to use its wi-fi, consider just how much worse things could be.

About the author

Ed Sikov is the author of 7 books about films and filmmakers, including On Sunset Boulevard:; The Life and Times of Billy Wilder; Mr. Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers; and Dark Victory: The Life of Bette Davis.

Dalton Trumbo and the “Unfriendly 10”

Dalton Trumbo and the “Unfriendly 10”

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Jason Rezaian

Jason Rezaian

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Osip Mandelstam

Osip Mandelstam