What makes a character an antihero? Certainly, he must be a protagonist who doesn’t display traditionally heroic traits, but there must be more. The reader must truly root for the character; we must be drawn to him despite ourselves. Perhaps his motivations are impure, his choices unconventional, but ultimately he must possess a certain allure that ignites our sympathy and engages our interest. The antihero is complex and unknowable, and because of that, he is fascinating in ways a pure hero or villain could never be.

Below are ten of the greatest antiheroes in literature.

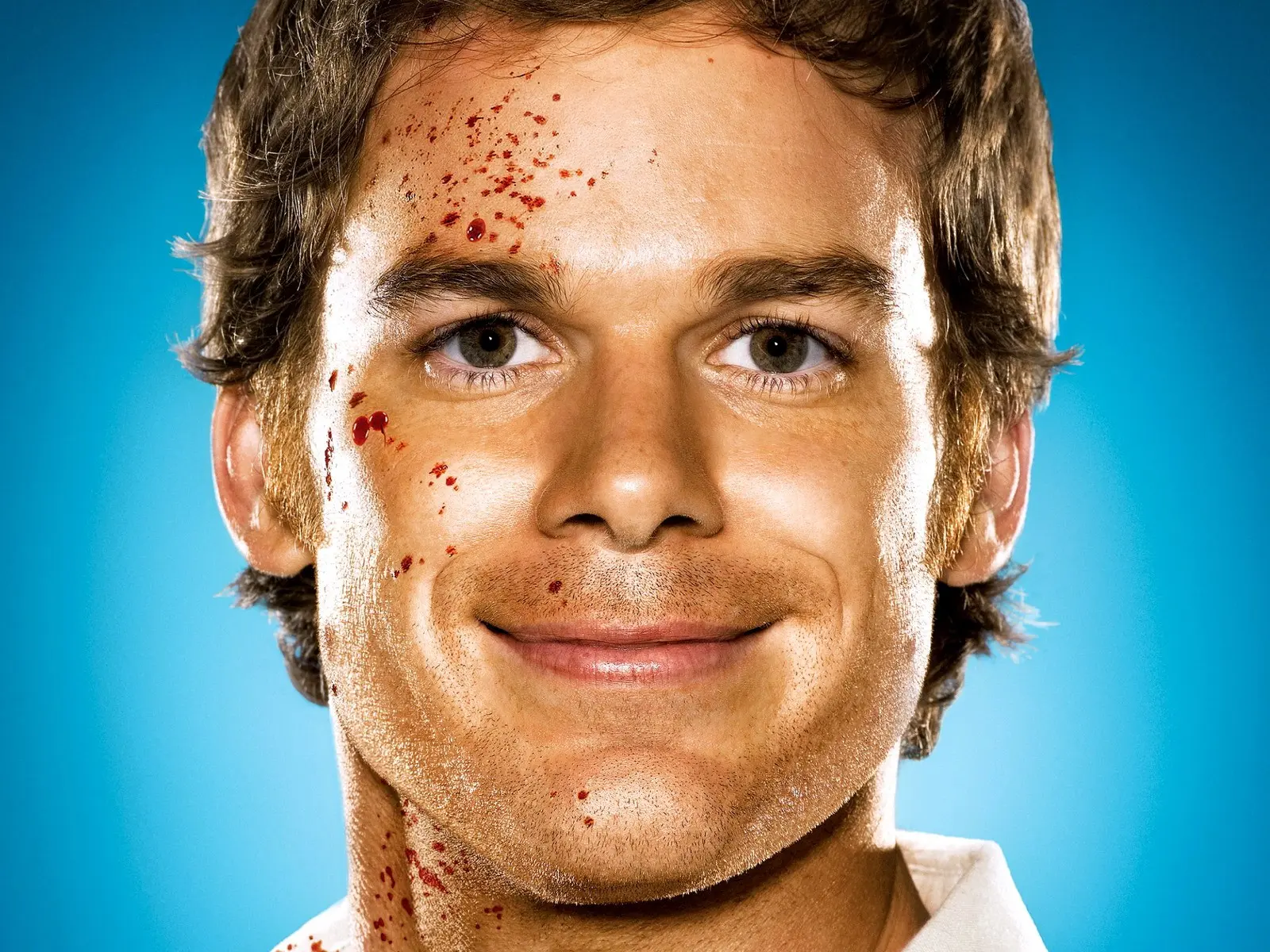

![]() 1. Dexter Morgan, Jeff Lindsay’s series beginning with 'Darkly Dreaming Dexter' (2004)

1. Dexter Morgan, Jeff Lindsay’s series beginning with 'Darkly Dreaming Dexter' (2004)

What can be more definitively antiheroic than a serial killer that the audience supports and applauds? While Lindsay’s crime novels make for somewhat insubstantial fare, he created a nuanced and enthralling character in the man who is compelled to kill, yet kills with a conscience. Try as Dexter might to convince the reader that he is without scruples, he cares deeply for those close to him and he only kills confirmed murderers who have escaped justice. He is also profoundly intelligent, working as a forensic blood splatter analyst for the Miami Police Department during the day. Dexter’s dueling purposes make him intriguing and kinetic, and the character is only served by Michael C. Hall’s charismatic and layered performance in the Showtime series Dexter.

![]() 2. Edward Rochester, Charlotte Bronte’s 'Jane Eyre' (1847)

2. Edward Rochester, Charlotte Bronte’s 'Jane Eyre' (1847)

Rochester is the gruff and enigmatic employer of the governess Jane Eyre, a bewildering character who makes detestable decisions throughout the novel. He locks his wife in the attic; he falls in love with his innocent governess and tries to trap her into bigamy; he then attempts to seduce her into licentiousness once his marriage is revealed; he lies repeatedly; he leads on a wealthy woman and allows her and Jane to believe he will propose; he is proud and will not ask for help when he needs it. When I list it all out like that, he sounds really bad. However, I believe Rochester is one of the first feminist male characters in literature. He locks his wife in the attic because she is mad and he was tricked into their marriage; he provides her with care and comfort rather than throwing her into an inhumane institution as would be well within his rights at the time. He respects Jane, admires her intelligence and talent, and he treats her as an equal. Rochester is deeply flawed, but his worst mistakes—the lying, the temptation—are due to his ardent love for Jane, and he overcomes those sins through Jane’s pure and blameless love.

![]() 3. Hannibel Lecter, Thomas Harris’ 'Hannibal' series beginning with 'Red Dragon' (1981)

3. Hannibel Lecter, Thomas Harris’ 'Hannibal' series beginning with 'Red Dragon' (1981)

Another serial killer! Lecter is an inarguably compelling character, initially making his influence known in the shadows of Red Dragon and Silence of the Lambs before embracing the spotlight as the protagonist in Hannibal. Lecter was a brilliant and successful psychiatrist before his pesky serial cannibalism landed him (sporadically) behind bars. He is engaging because he is elegant, well-mannered and ingenious. But it isn’t until his dealings with Clarice Starling in Silence of the Lambs that Lecter becomes sympathetic. His fascination with and empathy for Starling humanize Lecter, and this provides the reader with an area of common ground. We are also fascinated by Starling, and the more Lecter values Starling’s worth and wants to help her, the more hooked we are. Like Dexter, Lecter’s written character is also helped by a tremendous onscreen performance—two, actually. Brian Cox is quite good in Manhunter, but Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs and Hannibal—well, he is iconic.

![]() 4. Holden Caulfield, J.D. Salinger’s 'The Catcher In The Rye' (1951)

4. Holden Caulfield, J.D. Salinger’s 'The Catcher In The Rye' (1951)

Holden is an embittered, apathetic teenager. He’s intelligent and wants deeply to be someone of substance, someone authentic and honest. But as much as Holden detests all that is hypocritical and “phony,” like any teenager, he is a bit of a phony himself. He’s cynical and aloof, often quite mean to the people closest to him, and he spends the entire novel rebelling against the status quo for reasons that are unclear even to him. However, Holden is beloved and understood despite his many flaws. He’s a tragic character, finding himself on an inexorable journey toward adulthood (and thereby corruption) that terrifies and depresses him. We can relate to Holden because, even when he is not honest with himself, his words speak to a truth inside all of us, the part of us that remembers what it means to be a powerless, terrified and enraged teenager.

![]() 5. Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 'The Great Gatsby' (1925)

5. Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 'The Great Gatsby' (1925)

Gatsby is bright and glamorous, exuding charisma and power. But his success is built on an empire of lies; he is a bootlegger and an imposter, born the impoverished James Gatz. So much of the tragedy of the novel is due to Gatsby’s dishonesty, but we cannot blame him for his lies. His greatest sin is that he dreams big; he strives for wealth, for success, but most fervently, for the love of a woman who will never give it to him. Gatsby may be an imposter, but what he is most of all is a dreamer. And that is something the reader can understand.

![]() 6. Lady Macbeth, Shakespeare’s 'Macbeth' (~1603)

6. Lady Macbeth, Shakespeare’s 'Macbeth' (~1603)

Possibly the first antiheroine of all time, she is also the most difficult to embrace: the cold, hard Lady Macbeth. Her ambition guides her; she convinces her husband to murder the king and she is rewarded by becoming Queen of Scotland. Yet guilt haunts her, and she is never able to celebrate her achievement. She commits suicide after one of the most memorable monologues of all time: “Out, damned spot!” Lady Macbeth may be ambitious, but love for her husband and desire for his success are also behind her actions. She fears he is “too full o’ the milk of human kindness” to ever achieve power. Lady Macbeth is a challenging, complicated woman, but she is not fragile or retiring. She’s a ruthless, powerful woman who later proves to have a conscience, and that is an intriguing character, indeed.

![]() 7. Lisbeth Salander, Stieg Larsson’s 'Millennium' series beginning with 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' (2005)

7. Lisbeth Salander, Stieg Larsson’s 'Millennium' series beginning with 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' (2005)

Lisbeth is a socially inept computer hacker with few scruples and an unequivocal sense of vengeance. Lisbeth’s rules are unlike those of normal society: you rape her, she’ll rape you. You steal from her, she’ll steal from you. You piss her off, she will tase your ass. But she is brilliant and fiercely loyal; she defends those who are not as capable of defending themselves as she. Lisbeth is complex and compelling and absolutely unlike any other character in literature, but boy, she is scary.

![]() 8. Michael Corleone, Mario Puzo’s 'Godfather' series beginning with 'The Godfather' (1969)

8. Michael Corleone, Mario Puzo’s 'Godfather' series beginning with 'The Godfather' (1969)

Corleone begins his life as a man of unimpeachable integrity. He is attending Dartmouth University, intending to go into politics, steadfastly avoiding the life of crime to which he was born. But after his father, Vito, is nearly assassinated, Michael is drawn back into the family business, and he soon discovers that his criminal inheritance comes more easily to him than he ever predicted. After his father retires, Michael steps into the role of Don to the Corleones, and circumstances and greed slowly work their way into Michael’s soul, ultimately corrupting that unimpeachable integrity. We are shown every inch of Michael’s descent, and so we understand it. We regret it, but we relate to it.

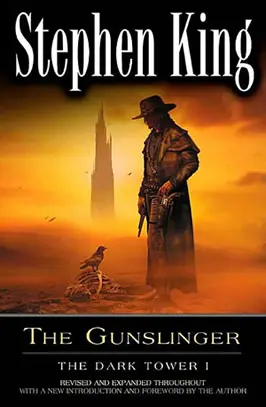

![]() 9. Roland Deschain, Stephen King’s 'The Dark Tower' series beginning with 'The Gunslinger' (1982)

9. Roland Deschain, Stephen King’s 'The Dark Tower' series beginning with 'The Gunslinger' (1982)

Roland is the hard-assed old gunslinger on a quest since time out of mind to reach the elusive Dark Tower. On this quest he betrays friend after friend. He allows loved ones to die; he kills others himself. He is cruel and cold because he must be, but once we grow to know Roland—know him as well as we know our own friends, after spending thousands of pages with him—we discover that each betrayal, each cruelty, cuts him far deeper than he will ever reveal. We forgive Roland for any breach of faith because every act of treachery is in service of his paramount quest: to save the universe. That’s pretty solid justification.

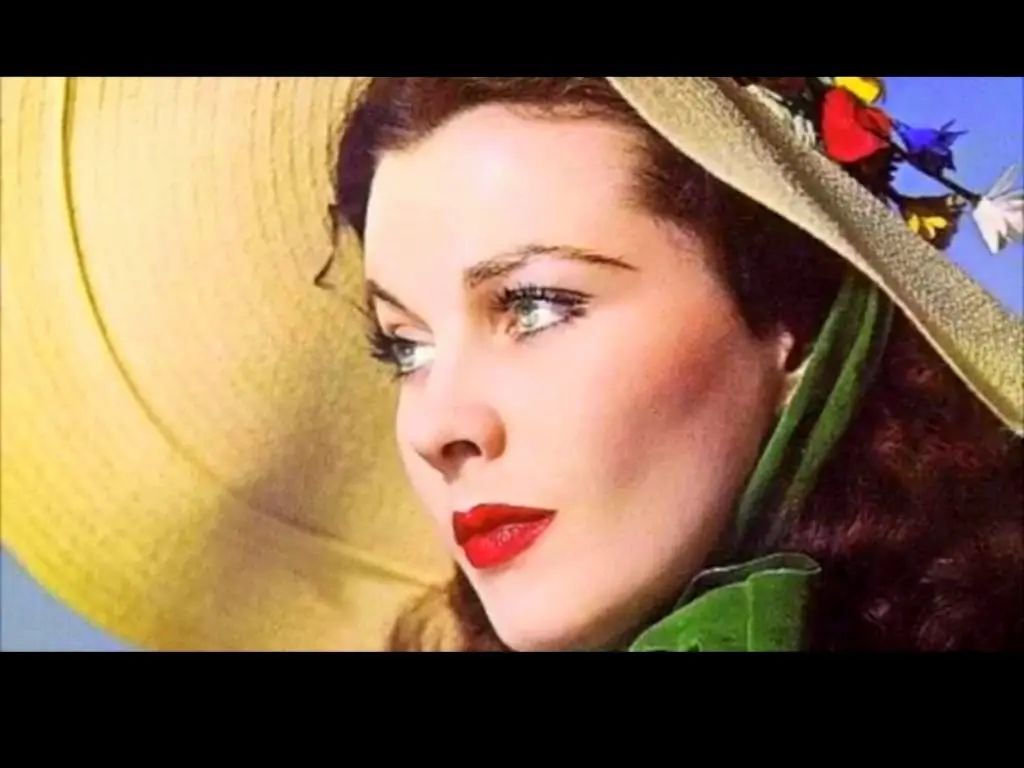

![]() 10. Scarlett O’Hara, Margaret Mitchell’s 'Gone With The Wind' (1936)

10. Scarlett O’Hara, Margaret Mitchell’s 'Gone With The Wind' (1936)

Katie Scarlett O’Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler is a petulant, self-serving antiheroine of singular status. She uses her beauty and charm as weapons, marrying again and again for jealousy, for money, for land—for every reason but love. She wears out husbands, backstabs friends and sisters, embraces carpetbaggers, hires convicts in dire working circumstances and breaks the hearts of many, many good men. But we love her for it—we love her because Scarlett does these things for one undeniable purpose: to survive. While the rest of the genteel South crumbles under the dismal weight of the Civil War, Scarlett endures. What she lacks in old Southern honor, she makes up for in strength and fiery temper, and they serve her through the lean and mean years of her life.

Writing this list struck me with the revelation that there are far too few female antiheroes in literature. More abound in comic books (Catwoman, Mystique, Black Widow), film and television (Nikita, Faith, Beatrix Kiddo), but I had trouble coming up with many antiheroines in literature. Give me your picks for antiheroes in the comments—and particularly any antiheroines I may have missed.

About the author

Meredith is a writer, editor and brewpub owner living in Houston, Texas. Her four most commonly used words are, "The book was better."

1. Dexter Morgan, Jeff Lindsay’s series beginning with 'Darkly Dreaming Dexter' (2004)

1. Dexter Morgan, Jeff Lindsay’s series beginning with 'Darkly Dreaming Dexter' (2004)

2. Edward Rochester, Charlotte Bronte’s 'Jane Eyre' (1847)

2. Edward Rochester, Charlotte Bronte’s 'Jane Eyre' (1847)

3. Hannibel Lecter, Thomas Harris’ 'Hannibal' series beginning with 'Red Dragon' (1981)

3. Hannibel Lecter, Thomas Harris’ 'Hannibal' series beginning with 'Red Dragon' (1981)

4. Holden Caulfield, J.D. Salinger’s 'The Catcher In The Rye' (1951)

4. Holden Caulfield, J.D. Salinger’s 'The Catcher In The Rye' (1951)

5. Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 'The Great Gatsby' (1925)

5. Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 'The Great Gatsby' (1925)

6. Lady Macbeth, Shakespeare’s 'Macbeth' (~1603)

6. Lady Macbeth, Shakespeare’s 'Macbeth' (~1603)

7. Lisbeth Salander, Stieg Larsson’s 'Millennium' series beginning with 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' (2005)

7. Lisbeth Salander, Stieg Larsson’s 'Millennium' series beginning with 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' (2005)

8. Michael Corleone, Mario Puzo’s 'Godfather' series beginning with 'The Godfather' (1969)

8. Michael Corleone, Mario Puzo’s 'Godfather' series beginning with 'The Godfather' (1969)

9. Roland Deschain, Stephen King’s 'The Dark Tower' series beginning with 'The Gunslinger' (1982)

9. Roland Deschain, Stephen King’s 'The Dark Tower' series beginning with 'The Gunslinger' (1982)

10. Scarlett O’Hara, Margaret Mitchell’s 'Gone With The Wind' (1936)

10. Scarlett O’Hara, Margaret Mitchell’s 'Gone With The Wind' (1936)