The "final girl" is a potent concept that started off in academic circles but has recently entered into the mainstream. A final girl, the main character in slasher horror movies defined by the antagonist murdering the cast in various sordid ways, ultimately confronts and defeats the killer, who is in more ways than one an uber male that stands in for the patriarchy. Usually she is a "pure" character, with the stereotype being that she is a virginal “girl scout” type. This term was coined by Carol Clover, an American professor of film studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in her 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. But what’s been little discussed is the idea of the “final boy.”

Most pinpoint an early, if not the first, final girl as Jess Bradford in 1974’s Black Christmas, but the concept wasn’t really cemented until Laurie Strode in 1978’s Halloween. The character, played by Jamie Lee Curtis, embodies the traits that Clover would codify 14 years later. Perhaps the mainstream public first became aware of these traits with 1996’s Scream, in which the character of Randy defines the so-called rules of horror movies: no sex, no drinking or drugs, and never say “I’ll be right back.”

These are mostly erroneous rules, however, as Laurie Strode smokes marijuana in Halloween (even if she doesn’t appear to be that into it), and Alice in Friday the 13th (1980) had a previous sexual relationship with camp owner Steve Christy, yet they win the day. Those rules refer more to the likes of Nancy Thompson of A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), who is in every way a morally upstanding, courageous beacon of light, and resists sex with her boyfriend Glen. But the rules were necessary in Scream, as they paint an extreme that Neve Campbell’s Sidney Prescott is able to subvert through her more progressive actions, including being sexually active onscreen.

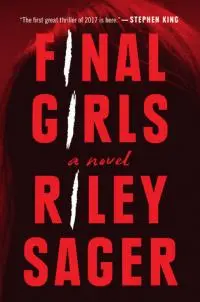

In the years that followed Scream the engagement with this concept has become even more blatant. 2006’s Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon, a mockumentary about a film crew following a slasher in training before a big night of killing, has the titular character discuss the trope, although he calls her a “survivor girl.” In 2015 two movies came out, Final Girl and The Final Girls, that both play around with this idea of a young waif unexpectedly fighting back. And if those two movies were small, little known horror movies, the term finally blew up this last July with the release of Riley Sager’s Final Girls.

The book follows three women that survived killing sprees years ago, and have been dubbed “final girls” in a bit of meta-narrative winking at the audience. In the present day they are targeted by a killer and have to team up to defend themselves. It’s an intriguing premise, as very few horror franchises deal with the aftermath for a survivor (some do, like Nancy in A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 3: The Dream Warriors and Laurie’s PTSD and alcoholism in Halloween: H20). There’s also the fascinating bit of trivia that the author used a pseudonym, as his real name is Todd Ritter.

The book follows three women that survived killing sprees years ago, and have been dubbed “final girls” in a bit of meta-narrative winking at the audience. In the present day they are targeted by a killer and have to team up to defend themselves. It’s an intriguing premise, as very few horror franchises deal with the aftermath for a survivor (some do, like Nancy in A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 3: The Dream Warriors and Laurie’s PTSD and alcoholism in Halloween: H20). There’s also the fascinating bit of trivia that the author used a pseudonym, as his real name is Todd Ritter.

This is provocative because although the conceit of final girls is taken from academia and horror movie circles, it’s very likely that Ritter was hoping to capitalize on the ubiquity of “girl” in the title of popular novels in recent years. From The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to Gone Girl to The Girl on the Train, this silly trend doesn’t look to be subsiding any time soon. And although the Millennium Trilogy, that also included The Girl Who Played with Fire and The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, was written by a man, Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl seemed to set a standard that has propelled fiction by women, about women and predominantly for women into the stratosphere. So did Ritter use a purposefully androgynous nom de guerre in hopes of hopping onto that Flynn money train? It seems likely, as many have speculated that something similar was done with J.P. Delaney’s The Girl Before, released in January of this year, with the author using his initials for the sake of ambiguity.

What’s provocative about all this is the final girls that Clover wrote about were all created and written by men, and the same is true of final boys that have sporadically appeared over the years. Take, for instance, the three most prominent final boys in horror history: Tommy Jarvis, originated in Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984); Jesse Walsh of A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge; and Tommy Doyle, who takes center stage in Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (1995). Each bucks the trends established as criteria for being a final girl and, in fact, mostly function for what they are rather than for what they’re not.

Tommy Jarvis, as first portrayed by Corey Feldman, is a 12-year-old boy. Although children are not necessarily off-limits in slasher films, in practice they tend to survive just because the killer, as written, is more interested in the nubile teens. In Tommy’s case, one would think being a child would exclude him from the requirements for death in a horror film, namely sex and drugs, but the movie goes out of its way to show that he’s titillated by naked girls. His house is next door to a cabin where the main teens are staying, and an entire scene is devoted to him peeping as one of the girls undresses in front of the window. In the end he is able to defeat Jason by essentially becoming Jason, shaving his head and applying makeup to look like the murderer when he was a little boy. The ending even suggests that Tommy has become a madman himself. The character shows up in the two sequels, a little older in each, and although he never kills anyone his behavior and relationship toward Jason Voorhees is kept consistent: he doesn’t drink but he certainly shows an interest in woman, and is never punished for it.

Jesse Walsh is a complex and rare case, and this has been well-documented in the last 32 years, of a male character struggling with their sexuality in a horror movie. Jesse is played by Mark Patton, an actor that was out at the time of filming the movie and had even already portrayed a gay character in 1982’s Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean. In Freddy’s Revenge, Jesse’s family moves into the house on Elm Street occupied by Nancy in the original movie. Immediately paranormal activities start to happen, and Jesse finds himself possessed by Freddy. And what becomes clearly very quickly is that Freddy is used in the movie as a metaphor for Jesse’s repressed homosexuality. And, ironically, the movie presents sex with his girlfriend Lisa as positive, and something circumvented by Freddy who hopes to tap into Jesse's repressed feelings.

Jump ahead a decade to Tommy Doyle in Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers. The character originated in the first movie, as a little boy that final girl Laurie is babysitting and whom she protects. By the sixth movie he is a grown man played by Paul Rudd (in one of his first screen roles) who has been investigating Michael all these years. He’s living across the street from the old Myers house, monitoring the place daily, and researching into the masked murderer’s evil. What’s fascinating is how the character, as written and performed by Rudd, is rather eccentric and even borders on being threatening himself. He’s twitchy, stalker-ish (watching Kara Strode through a telescope), for half the movie it’s left ambiguous whether or not he’s a hero or a lunatic, and even in the end when he is faced with Michael for the first time in years Rudd plays it like he’s grateful to have confirmation he’s not crazy.

What’s the main difference between the final girl and the final boy is while the final girl is in many ways the exact opposite of the killer, the final boy is in many ways a mirror of the killer. The girl is weaker and more pure, representing everything that the killer is not, while the boy is one step away from becoming the killer. In the case of Tommy Jarvis he has to become Jason in order to defeat him, while Jesse literally turns into Freddy and has to be saved from his darker tendencies by a final girl.

With that in mind, it is worth pointing out that all three of these movies have a final girl. The Final Chapter has Tommy’s sister Trish, Freddy’s Revenge has Lisa, and The Curse of Michael Myers has Kara. But unlike most slasher movies in which the final girl has to face the killer alone in the end, these three have them as co-leads, with the final boy as the protagonist. And in the case of final girls being the lead, they have a very specific arc of taking the power from the killer.

As Clover’s thesis is bluntly articulated in Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon, the final girl is “empowering herself with cock” when she rises up against the killer in the climax. This is more often than not done by robbing the killer of his power, literally taking away his phallic-shaped weapon. But in the case of final boys, it’s a slight tweak, as it’s not so much taking the killer’s power, robbing them of their machete or finger knives, but becoming like the killer.

A final girl may be pushed to the edge, bloodied and mad-eyed, but very rarely do they take on the traits of the killer. A final boy, however, as demonstrated by Tommy Jarvis, Jesse Walsh and Tommy Doyle, end up becoming like the killer. In the case of the former two the endings of their movies actually suggest, even though the intervention of the final girl temporarily stalled things, they will go on to be killers. Only Tommy Doyle gets out without being tainted, although going by the theatrical cut of Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers, he succumbs to a kind of unhinged rage that allows him to physically defeat Myers.

Perhaps more modern slasher films will offer different perspectives on both the final girl and the final boy. As new filmmakers, especially women, tackle the material the old archetypes can be shed or examined with a new perspective. But the very few examples provided paint a picture of girls emasculating men in order to defeat them, while men can only win by becoming more of a man.

Get Nightmare on Elm Street 1-7 at Amazon

Get Final Girls at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.