Hero's Journey via Wikipedia Commons, public domain

Last January, my late-onset agoraphobia took a plunge — I joined a weekly Friday night online group for outsider and transgressive authors to share and critique one another’s raw work. Having little idea what to expect, I was initially on edge; only to be warmly welcomed by some of the most sincere and humble/humbled people I’d met in some time. Once the challenging, often white-knuckling works began to be read, I knew I had found my crowd. While this group is serious about their work, they do not take themselves seriously — a cool drink of water in our culture-war wasteland where I felt I was finally able to unfurl, relax, and explore sharper angles of human nature; where style and approach could be discussed and critiqued without judging the actual content it takes to get there.

On one recent Friday night where the laughter and jovial comraderie was at a particular high, someone reflected: “Why does this group work so well, considering most members are drug addicts/alcoholics, ex/present cons, misanthropes, cancellation refugees, dating site rejects, and the struggling mentally ill?”

It was a great question, considering we could be such an immediate magnet for drama and communal decay. But without blinking, my thesis was tempered: 1.) Because you can’t really define transgressive literature —you know it when you see it — so no one is trying to outdo one another in order to represent the nebulous form and 2.) Because no one’s work is following the antiquated narrative arc of the hero’s journey.

Since there are no heroes, there are no villains in these works — no conveniently placed epiphanies, redemption nor victorious homecoming. Therefore, no one is really arguing what is wrong or right, and no one involved feels they are owed anything. It’s bolstered some daring work from writers turning themselves inside out; pieces that often haunt me for days after. Words that feel a lot like truth.

Since then, I’ve re-evaluated some of genre-fiction I’ve written for the past five years — crime, horror, and sci-fi, particularly — where I hated following the narrow-minded monomyth that’s been cursing humanity since the days of the Bible. While I’m confident in my writing, I have a theory some of my work might have been rejected in these genre venues because it doesn’t scratch that hero myth itch with editors — that generally satisfying familiar path turned omnipresent curriculum by Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth:

1. Call to adventure.

1. Call to adventure.

2. Conflict.

3. Death/rebirth/revelation

4. Transformation/Atonement

5. Return to home.

"The secret about home is that it actually doesn’t exist. Home is just a foundational state of being. You’ll spend your entire life trying, and failing, to return to it."

— Jon Lindsey, Body High

Since our culture is inundated with the unrealistic outcomes of the hero’s journey, one of its largest misinterpretations is that we tend to see our own lives as a story; as if we are still children who think we get a prize for being good.

As if the bad guys get punished for not following our script.

In fact, we see the hero’s journey most rigidly followed in the Hollywood blockbuster film. It’s the chiseled male swashbuckler whose opposition conveniently fall to their knees, a girl to fall into their arms because he walked on the proverbial hot coals. Or the empowered heroine who triumphantly dazzles the patriarchal world who previously doubted her. It brings us a quick buttered-popcorn dopamine hit that fools us into believing anything is possible, despite the fact it’s merely the same story being told to us over and over again. These tales leave us empty once we return to real life, their portrayed achievements — even as analogies — prove unattainable in reality because we aren’t able to recognize them in our daily narratives, unless we find ways to desperately shoe-horn it in there.

“I don’t think there are any rules, but I like to respect the boundaries of storytelling, put the characters before the plot. That I know to be 100% truth,” says screenwriter and recent Scripts4Change winner Anthony Todaro. “It’s not about the journey, it’s about the character’s inner voice — that lie they perceive to be truth which causes all the commotion and conflict. Otherwise, those who prescribe to a set system might be condemned to repeat mediocrity.”

Last year, I blew through every episode of Cobra Kai in a weekend, a rare instance of binge-watching for me as I usually avoid contemporary TV shows for their predictable and pandering plots. But what made the Karate Kid spin-off such compelling television was its complete subversion of the narrow hero’s journey of its original source material. The roles of hero and villain switched more times than you could count, the grey areas ever-widening until you didn’t know who to cheer for — the viewer was able to see themselves or someone they loved in some of the most repellent characters. But what made each character become the bad guy? The narrow-minded self-righteous tunnel vision and unchecked anger —the fastest way to belittle the points of our plight. This I see as one of the more blatant trip ups when we confuse the hero’s journey with our real lives.

Now, every time I return to the genre-crowds – most notably, the indie crime-fiction world – it tends to be inflamed with drama and infighting, instigated by those who shoot first and ask questions later or not at all, under the guise they are defending a standard that exists only in their heads — possibly their ill-conceived hero’s journey so insular they have made themselves judge, jury, and executioner while the rest of us are simply trying to block out the noise and write.

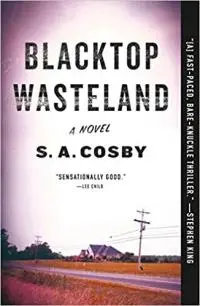

One of the biggest crime-fiction novels of last year was S.A. Cosby’s Blacktop Wasteland (Flatiron Books, 2020). The love for this Southern rural-noir was across-the-board unanimous, the way the fast cars felt propellent with the emotional drive of the story — and Cosby’s very organic rise proved the book’s vast accolades were authentic. But for me, the best part of Blacktop Wasteland is rarely mentioned at all — its perfect last line that’s a grand statement of the imperfect as a means to an end. As we rode passenger in Bug’s getaway car for 285 pages, his speedometer in the red as he left a trail of conflicted destruction behind him, his wife Kia asks: “You’re never really gonna change, are you, Bug?” The statement came out flat and listless. Some might say hopeless. Finally, he whispered, “I don’t know if I can.”

Anyone who hoped this dangling sentiment leaves room for a sequel, to see if Bug maybe can change, is missing the point. It’s a master stroke for Cosby, this line that immediately challenges the reader to take inventory of themselves, to see if they can identify with this man who’s quite possibly beyond traditional family-value redemption, and then that’s the end of the line! It left me disintegrated, yet oddly comforted that I wasn’t alone — and hopeful that others have the guts to go there.

Anyone who hoped this dangling sentiment leaves room for a sequel, to see if Bug maybe can change, is missing the point. It’s a master stroke for Cosby, this line that immediately challenges the reader to take inventory of themselves, to see if they can identify with this man who’s quite possibly beyond traditional family-value redemption, and then that’s the end of the line! It left me disintegrated, yet oddly comforted that I wasn’t alone — and hopeful that others have the guts to go there.

While I hold-fast to my penchant for redemption be damned, I blindly asked a smattering of authors what they thought of today’s relevance of the hero’s journey, to see if I could get some counterpoint. Instead, their spontaneous thoughts on the matter largely bolstered my thesis of it's increasing obsolescence.

“I’d say the hero’s journey is justified — it’s a reflection of the need for sacrifice and the need to gain growth,” says Max Thrax, author of the upcoming God Is A Killer (Close to the Bone, 2022). “But how ‘heroic’ the character is depends where you choose to stop the narrative. For example, Oedipus the King is a hero’s journey, but with a highly ironic end. Those are the ones I like the most. In noir and gangster stories there is a journey of sorts but at the end, failure is guaranteed. But the current ubiquity of hero’s journey has a lot to do with the popularity of Star Wars and post-80s Disney. It’s canned, part of a manual now.”

“If we’re gonna talk about any shortcomings of the hero’s journey, why not start with the form that subverts it — autofiction,” says Josh Sherman, writer/editor of online journal Charm Reduction. “Through recording their own lives in fiction, these authors often learn something about themselves and in turn, show readers how they might do the same. I don’t think traditional fiction, with its narrative tension and all it’s ‘craft’ elements can provide the same experience. But then there’s the question of the reader’s growth — is that why you’re reading? I’m not sure how much personal growth I get from listening to the same disco record a hundred times, but you don’t need a plot if your voice is a song.”

“Most minority narratives default to the hero’s journey of the American Dream but that coin has two sides,” says Argentinian writer Jahzeel Vasquez. “Not everyone goes to college — they moonlight as a safe way to pay bills or find themselves in unstable relationships for housing, which, according to the hero’s journey, mean they are ‘flawed’ and need to change in order to ‘get there,’ whatever that means. But these options are valid. Expecting anyone to change is going against their autonomy — this is especially true for minorities. We are plagued by stories where minorities are ‘winning,’ correcting their flaws, which in the end feels performative or at the very least, reductive.”

“I've often felt like the hero's journey doesn't capture what a woman goes through,” says Autumn Christian, author of Girl Like a Bomb (CLASH Books, 2019). “Even on a metaphorical/consciousness level it feels incomplete to me. The closest to a female ‘hero's journey’ is probably what we find in romance novels. But still, not quite. Regardless of gender you will have to ‘slay a dragon’ in order to achieve some kind of personality growth, but even the language is coded male.”

“As a template for confronting the outside world, the hero’s journey is not so realistic,” says Alec Cizak, author of Lake County Incidents/editor of Pulp Modern. “But as for the inner journey, the psychological journeys of life, I think it’s not only valid but necessary for growth and maturity. And ultimately, even in a material sense, we do end up where we began — oblivion. But we are very changed by the time life circle’s back to that lonesome beginning/end.”

Get The Power of Myth at Bookshop or Amazon

Get Blacktop Wasteland at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.