A couple of months ago I finished Erin Morgenstern’s wonderful book The Night Circus. The Night Circus is a romantic voyage through a world of urban fantasy set in the late Victorian era. In many respects, it reminds me of Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke, which is currently being made into a BBC television series. (Morgenstern herself acknowledged her love of Clarke’s book when she appeared last fall at Wordstock in Portland, Oregon.) However, Morgenstern has different sensibilities as a writer than Clarke. Clarke’s Hugo award winning book reads like an annotated work by Jane Austin. You really have to like world building and love Napoleonic era literature to be able to fully appreciate Strange and Norrell. Some critics consider it primarily a work of alternative history rather than fantasy. On the other hand, Morgenstern approached her work in a slightly different fashion. Much more a work of fantasy, Morgenstern evokes the gas lamp era as a canvas on which to play. Its history is much more in the background than the Napoleonic era’s is for Clarke.

What ties Morgenstern and Clarke together is the way in which they insist on placing their fantasy elements right smack in the middle of the every day world. This isn’t Harry Potter, in which the magical community has separated itself from the rest of society. Clarke and Morgenstern put the fantastic within our midst without it appearing out of place. It might take place in the coffee shop while you sit there reading this blog post on your iPhone. This isn’t what many readers expect and in that way it breaks the conventions of traditional fantasy storytelling. For Clarke the magic of Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is a dying art, only remembered and practiced by the few accepted in society. For Morgenstern magic is right with us every day, but we do not perceive it. No need for squads of “obliviators” here. We are just too prejudiced and unaware to perceive what is right in front of us. This break in the conventions of fantasy storytelling is what sets Morgenstern and Clarke apart from the crowd. It makes their works more interesting than if they followed more tried and true means of fantasy world building.

Morgenstern breaks storytelling conventions of another sort in her book, and, as a writer, I find this break much more fascinating. When you begin The Night Circus, you are almost immediately introduced to the central conflict of the book. However, as a reader you are not told the stakes of the conflict nor its exact scope for nearly 150 pages. This is an incredibly risky strategy for Morgenstern. The danger is that her readers will either be irritated by being kept in the dark about why they should care for the characters and their dilemma, or they might get bored because the storytelling tension feels contrived and weak. Yet one of the things which makes Morgenstern’s book so wonderful is that she succeeds in breaking the rules of how a storyteller should tell their story.

Morgenstern isn’t simply an iconoclast. She delays telling the readers of her story the stakes of the conflict for a reason. Her choice mirrors the experience of her main characters who also do not know the stakes of their “story” until many years into it. In this way breaking the conventions of storytelling exalts Morgenstern’s work rather than diminishes it.

However, her choice comes at a cost. Morgenstern must work doubly hard at other aspects of storytelling to make her gamble pay. It succeeds only because she is a master of prose. Her words are beautiful to read and enjoyable as art in themselves. Her world building is elegant and thick. This is a fantasy world I want to inhabit. She populates this world with an intriguing cast, both attractive and familiar, yet somehow inaccessible as circus performers and magicians ought to be. For many pages, Morgenstern depends on these strengths to make her work hold together when she has intentionally withheld understanding from her readers. It's like watching a great illusionist at work, and I recommend that anyone who respects the craft of writing, particularly newly minted writers, should read it.

Morgenstern’s success demonstrates one way in which a budding author can stand out from the crowd is by strategically breaking “the rules” of storytelling. However, if an author chooses this path they must work excruciatingly hard to make sure their other story elements are top-notch. In order to break the rules, an author must know why the rules exist and what they hope to accomplish when they break them.

I have said that if I could go back in time, I would seriously consider visiting George Lucas just before Star Wars came out. I would sit him down over a coke—cola, not the other kind. (I feel the need to explain because it was the ‘70s after all.) Anyway, I would sit down with George Lucas and encourage him to never mention in any media interview, book, or conversation that he was inspired by reading Joseph Campbell. If Lucas would have complied, I believe the he and I might have saved the planet from a scourge of soulless paint by number blockbusters that substitute fidelity to a formula for great storytelling.

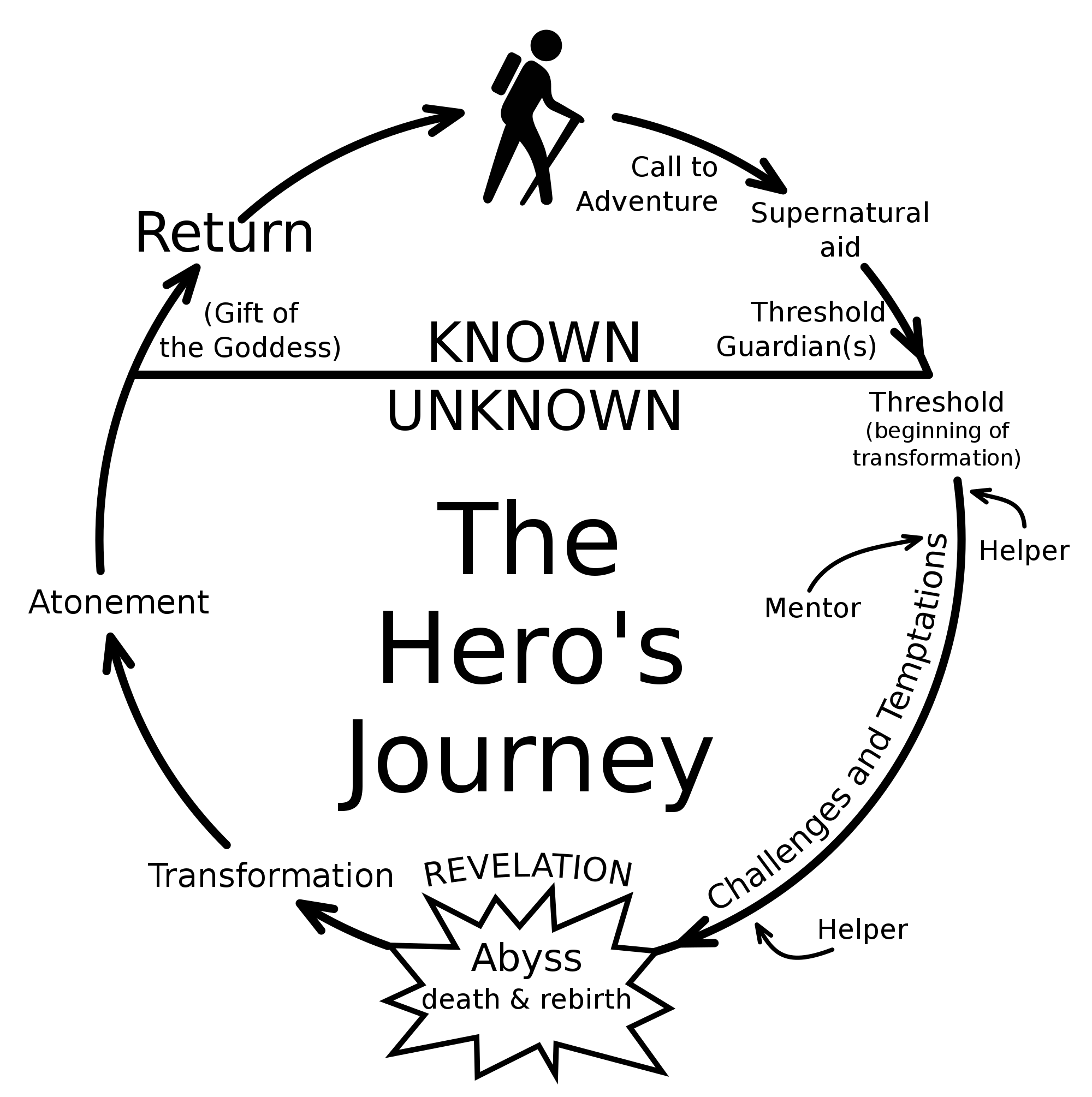

None of which is to say that Campbell and his generation of scholars didn’t nail the structural underpinnings of many stories from around the world. But I am not sure that our obsession with his model has been good for storytelling, particularly in Hollywood. For one thing, once the curtain is pulled back on the little man at the microphone the great and powerful wizard isn’t so amazing any more. For another, being too aware of Campbell and his model often leads to cookie cutter thinking about what makes a story great. All stories begin to sound exactly the same. Campbell's model can be really helpful if you see it as a loose description of the kinds of story elements many great stories often contain. However, it becomes a strait jacket if you see it as the model you must follow.

None of which is to say that Campbell and his generation of scholars didn’t nail the structural underpinnings of many stories from around the world. But I am not sure that our obsession with his model has been good for storytelling, particularly in Hollywood. For one thing, once the curtain is pulled back on the little man at the microphone the great and powerful wizard isn’t so amazing any more. For another, being too aware of Campbell and his model often leads to cookie cutter thinking about what makes a story great. All stories begin to sound exactly the same. Campbell's model can be really helpful if you see it as a loose description of the kinds of story elements many great stories often contain. However, it becomes a strait jacket if you see it as the model you must follow.

But don't tell that to the movie studios. If you intend to sell your script in Hollywood, you better learn to paint by the numbers. You don’t dare break any of the rules. Or if you do break the rules, expect someone at the studio to change your script down the line and make it more faithful to Campbell’s hero's journey model.

I think this is exactly what happened to the recent film, Oblivion, which is absolutely stunning and has a great premise and a tight, well written first act. (In my opinion these features alone make it worth viewing in the theater.) Then the Joseph Campbell zombies intervened and a story that was heading toward greatness settles down into mediocrity. Morgan Freeman’s character and the narrative it forces on Oblivion weakens the whole film. The film worked well until fidelity to the model forced a mentor and helpers down the throat of a script which should have revolved around four characters. It never recovered. It is interesting to note that visually the film also lost all of its beauty whenever Freeman’s bland character appeared on the screen. It suddenly looked like a cheaply made Mad Max film. None of which is Freeman’s fault per se. The script just didn’t give him anything to do.

Thankfully, novel writers (particularly those of the self-published variety) are not nearly as bound by fidelity to Campbell’s model. They are more free to see it as a guide rather than a rigid path, but I would also argue that this freedom is no excuse for not being familiar with it. The hero's journey can be shown to under-gird story after story through centuries of storytelling in the east and west of the world. It does seem that this type of narrative is buried deep within the human psyche and audiences respond positively when it is done well. In fact, I would almost guarantee that 95 percent of the writers reading this post could go back and clearly identify the parts of the hero's journey in their own writing. Creators ignore it to their peril.

With this in mind, a creator, especially a young creator, often has two options when they approach the hero's journey narrative. First, they can do it exceedingly well. This is part of what makes Star Wars: A New Hope such a transcendent film. It does the heroes journey narrative exceedingly well and audiences love it. True, the movie also had cutting edge special effects and cool looking space battles, both of which helped it move from ordinary to extraordinary. However, these wouldn't have seem so glorious if the structure of the story hadn't been so faithful to the hero's journey model. Audiences still crave a good hero's journey and they probably will for centuries to come.

The more interesting option for a young storyteller is to tell a story that pays homage to the hero's journey model while critiquing it or challenging its tenets in some way. Here is where the freedom of novel writing can exalt a story above the ordinary. This is the path taken by Morgenstern. In The Night Circus the protagonists are long into the “challenges and temptations” of their journey before they understand the meaning and purpose behind their “call to adventure.” In fact, understanding just what is at stake functions in the story as a “revelation.” It leads to the “abyss.”

I have met writers and other creators hell bent on trying to excise the hero's journey narrative from our literature. Often they see its tendency toward redemptive happy endings as problematic when actual lives offer at best compromise and partial transformation. Sometimes they can produce interesting work, but often their work feels as stilted and cookie cutter as any Hollywood film which dots every “i” and crosses every “t.” They declare that their story will not contain a call to adventure or any characters that help the protagonist. More often they decide that they cannot write a protagonist who is "good" so they create an anti-hero and ask the audience for no apparent reason to root for someone behaving despicably. Sometimes these stories can work. More often then not they don't. Why? Because the changes are arbitrary rather than driven by the story itself.

In order to succeed, challenges to the hero's journey model almost always need to have a story driven purpose. In Morgenstern’s interview at Wordstock she made clear that she wasn’t thinking deep thoughts when she set out to write her book. She just wanted to tell a really great story. The kind of story she wanted to read. In that story it made sense not to tell the reader what the characters didn’t already know. Her decision to challenge the model had a story driven point.

Authors may or may not also choose to compensate their readers for the irritation caused by challenging the normal path of a story. Morgenstern works hard to compensate readers for their irritation with luscious descriptions and a fantasy world that is wonderful to explore. Without such great prose and world building her story may not have worked.

On the other hand, authors do not always have to compensate readers for their irritation. For instance, I conclude my book Aetna Rising at the “abyss.” The main character drops in and the book ends with a promise that I will remove him from the “abyss” in the next book. I have had many a criticism on Amazon for that choice. Readers get mad at my ending. But as I explained to one of my critics, the choice was intentional. I left my character in despair because I wanted to challenge the notion that once a character chooses to love suddenly everything turns out good. In my life and the lives around me the choice to love someone is often only the beginning of the trouble. People don’t often live happily ever after without a lot of hard work. Stopping my story right where I did highlights this truth about life. If I had moved on and shown the rest of the journey no one would have thought twice about how painful it can be to love in their own life. They would simply remember the ending.

It remains to be seen whether or not I can pull off an ending which will make the irritation I caused my readers worth it. I know that I am trying hard to make Aetna Adrift better than Aetna Rising. So maybe I am trying to compensate my readers after all. I hope to create a case of delayed gratification. (For those of you waiting, you should know that I have been working hard and my critique group has been poring over drafts. I am expecting to have it ready by late June.)

How and why an author challenges the hero's journey model is up to them. My advice for a new author is simply to be intentional about your choices. Make sure you know the storytelling purpose behind your decisions and don’t be afraid to challenge the model. It can lead to good things.

About the author

I am a full time writer and blogger living in Vancouver, Washington. I am an author of both non-fiction and fiction, as well as a contributor to the GeekDad blog on Wired.com. I write on a wide range of topics. I am the author of two published pieces of Science Fiction and a best selling book on everyday personal finance. Currently I am working on my third story set in the Pax Imperium universe and a book on how to survive serving on an HOA or Condo Association board. When not waxing poetic on various aspects of fiscal responsibility, I tend toward the geeky.

When not poised over the keyboard, I love to spend time with my family. I am married to an angel, Jaylene, who has taught me more than anyone else about true mercy and compassion. We are the parents of three wonderful girls. As a group we like swimming at the local pool, gardening, reading aloud, playing piano, and beating each other soundly at whatever table top game is handy.