Quite often in my classes, and my own studies, the way I teach, the way I learn and grow is from studying stories that I think are amazing. Whether it’s a genre I like or a particular style or just the fine execution of story with a powerful voice, if a story gets a high rating from me (say in the 8-10/10 range) then I revisit it, study it closer, and try to see what it can do for MY writing. It might have great setting, an original plot or story, a unique twist on a classic monster or trope, or a lyrical voice that proves to be immersive. There are so many reasons that a story can stand out to me. But what about the stories that we deem “bad,” what can we learn from them? Let’s dig in and find out.

What Is A Bad Story?

So there are two different types of “bad stories” that I’m going to talk about today. The first is a story that we might deem bad due to the writing—cliched plot, lack of setting, characters we don’t care about, no resolution or change—whatever we determine to be essential in a reading experience. This can vary, but most teachers, editors, and writers will say that there are certain elements that must (or should) be present. I look at Freytag, and that includes the title, the narrative hook, the inciting incident, exposition, internal and external conflict, rising tension, leading to a climax, resolution, change, and denouement. You can play with these elements, you can break the rules, but quite often I find that when a story doesn’t do what most educators say are mandatory, the story often fails.

The second kind of bad story isn’t really a bad story at all, it’s just a bad story for US, for me, for you—in any given moment. So keep that in mind as we’re talking. You might hate a certain genre entirely, or not like particularly violent or graphic horror. You might only like psychological tales, with an intellectual element, or something that has humor. So these stories are tales that we just don’t like due to personal taste. For your own growth as a writer, eliminating genres, certain authors, certain stories because they don’t work for you doesn’t mean they are technically bad, poorly written, or without merit—they just don’t work for YOU—in this moment, or maybe ever. And that’s okay! Make a list of authors that don’t work for you, and move on to voices that do. Don’t feel like you have to read an author because they are successful, or widely taught, or in a great magazine (or anthology). If you don’t like them, just read something else. It’s okay! Honest.

Diagnosis

So when you read a story and it doesn’t work, do you ever slow down and ask yourself why? This is what I want you to do. It’s what I do with the stories I read for pleasure that I like or love, and it’s what I do for the stories I teach in my classes—the ones I think are special. It’s just as important to try to figure out why that story didn’t work for you, and then to see if that has a relationship to your own writing. Here are some things to consider.

-

GENRE—if you find that you just don’t like splatterpunk, or really violent fiction, and think that it’s low-brow, or weak to rely on a gross-outs, or death to create a false emotion or impact, then feel free to avoid those genres (and sub-genres). These are probably going to be genres that you don’t want to write, either.

-

LENGTH—For some readers there may be a certain length that doesn’t work for them—such as flash fiction, or really long short stories (say 7,500 words or more) or maybe even novelettes, or novellas. Figure out what works for you. If flash just doesn’t do it for you, not enough meat on the bone, then pass on it, and probably don’t write it. Same for really long, slow, deep, layered, epic stories. If that sweet spot for you is 5,000 then you may want to avoid the longer stories. (Not to be confused with novels, as that is a whole other ball of wax.)

-

TROPES AND CLICHES—If you read a story that seems very familiar, if the dialogue is cliché, if the plot and tropes they use don’t do anything new for you, then you might be bored with such a tale. Now, maybe an exceptional author can take all of those common, expected elements and make it special through the lyrical passages, the poetry of their voice. Sure, that can happen. But what does this teach us? That most of the time we want to push hard to be original, different, unique, weird, and unexpected. Maybe you can take that werewolf or vampire or zombie trope and use that to access the narrative, as a comfortable way into the story, but you better do something more with it than the dozens of stories we’ve seen already. Tread new ground. Add what only you can add. Cliched stories will push you to do more with your own work. And that’s always a good thing.

-

DIALOGUE—Man, I really hate a story that has bad dialogue. What might that look like? The characters may say things that are dull, redundant, boring, and expected. The conversation may not match the character, their education, their job, and history across this story. There may be a lack of dialogue tags so we aren’t sure who is speaking. There may be really long passages of ONLY dialogue, with no setting, action, character, or sensory details. These can all be the kiss of death for me. So, what do I do with my dialogue? First, I don’t have a lot of it. And when people do speak, it’s usually important—revealing plot, or character, or setting. I also read my dialogue out loud, to make sure I’m not doing anything weird—do I stumble over words, do I find myself using a character’s name when I would never do that in real life, or not nearly as often? If you’re laughing at the dialogue or rolling your eyes (when you shouldn't be) then that may be an issue.

-

BAD OPENING—I’m sure you’ve read a story and wondered where the hell it was going, or even who the character was (man or woman, boy or girl, tree or demon), the lack of setting, the abstract opening, the confusion keeping you from being invested. The title is your first hook, and the first line is the second. Where does the initial paragraph go? You don’t need to spill all of the beans in the first 50 words, but if we aren’t sure of the genre, or the character, or any of the plot, or even where and when this is happening, you may lose your reader. Many bad stories don’t hook, and they don’t start close to the inciting incident (the moment in time after which things will never be the same). Your opening is not random, it is purposeful, and it is very important.

- BAD ENDING—Similarly, what does a bad ending look like? Well, it’s going to be too fast, too short. It’s not going to deal with the external or internal conflict—one, or both, did not get resolved. And by having no change, the reader will probably be unhappy, dissatisfied. Why did we read this if nothing was going to happen or change? Some experimental fiction can reside in only the sensation and emotion and abstract, but it is hard to pull off, IMO. Was the ending something you saw coming a mile away? Did you forget to add any sort of denouement—that epiphany and understanding of what has just happened to you, as the protagonist? Then this may come up short. You can have an open-ended story, you can be ambiguous, and the change can be as little as something like acceptance, or the desire to not change—but usually you need to address your hooks, your conflicts, the thing that you promised the audience, the expectation (subverted or not) fulfilled. I’ve said this in my classes, but if you went to McDonald’s to get a burger, and they gave you the wrong burger, you’d be upset, but it’s close. If you got a veggie burger, again, close, but not the meal you ordered. If you received a fish sandwich, you’d probably be upset. And if you got a hammer, you’d probably mutter curse words under your breath and lose your temper.

A Checklist

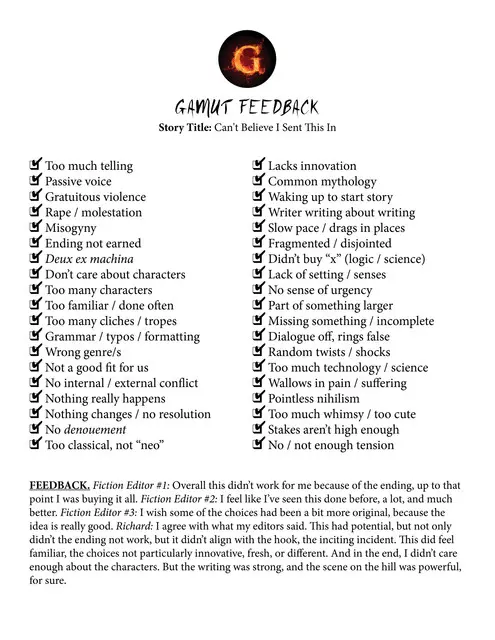

When I ran Gamut, we had a checklist that we were going to use to give feedback to authors that asked for it. In the end, the industry didn’t like us charging a small fee to do that, and so we didn’t set that up, but I do have that checklist right here, and I’m going to show it to you. These are the reasons that we might pass on a story that didn’t work for us. (The feedback is all fictional, this is not an actual story, or feedback we sent out.) Every publication is different, but this is a long list of things that you might want to look for in your own writing, so that you can avoid turning in a bad story. Best of luck!

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.