When you write about horrible people in your fiction—whether it’s your villain or your protagonist—their portrayal can’t be one note. What I want to talk about today is how you get readers to feel strong emotions about all of your characters, but especially the dark souls, monsters, and evil entities in your stories.

Their Role As A Villain

Yes, traditionally the villain is somebody you root against, it’s somebody (or some THING) that is trying to stop your protagonist from succeeding. Or perhaps they are just a dark presence in the universe, and aren’t even paying attention to your hero. Either way, you need to think about their initial role—as spoiler. They are there to help make the internal and external conflict of your protagonist more difficult. They are trying to get in the way, they are doing bad things, they are a stain on this planet (or wherever you have your story set). You need to get us to hate them, to actively fear them, there needs to be tension, anxiety, and worry. You need to show that person (or monster) doing bad things, so that we can form a strong opinion of them. But before we can hate, we have to care.

What is the Opposite of Love?

I’ve said this before, but the opposite of love is not hate, it is apathy. It is a lack of caring at all. It is indifference. In order to hate the dark characters in your short story or novel, we first must feel something. We must care. Now, that doesn’t mean necessarily that we have to have sympathy or empathy for them (though we will talk about that in a minute, their origin story, how they were once possibly innocent). How can we do that?

I think of the Slake Moths in China Mieville’s Perdido Street Station. They are horrible creatures, based on the skeletal frame of a butterfly, but the size of baboon. Over time we will grow to hate them, but first we must see how awesome they are. Part of what drives the connection to monsters is the fascination—whether it’s a werewolf, vampire, zombie, or something else. These Slake Moths start out as colorful, vulnerable, iridescent caterpillars, and we find them endearing, complicated, their synesthesia a captivating trait. Their victims literally cannot look away from them—they are hypnotized. Like when you drive by a car accident, it is hard to avoid staring. What they do to you once they’ve captured you, these Slake Moths? Well, that’s what makes them monsters.

So the key here is that we have to be eager to learn about these bad people, even if we find them disgusting; we have to wonder how it all works, when we know we should just run in the opposite direction; we need to figure out what their appeal is, as authors, and use that to manipulate the reader.

Innocence First

Another way to get us to care about your bad guys (villain or antagonist, monster or fallen hero) is to show them before they went bad. Sure, some creatures are born with base desires—to hunt, to eat, to destroy. Maybe they will never be more complicated than that. But quite often in fiction and film, these dark entities started out as something else entirely.

Was Hitler born a madman or was he a creative, innocent child who changed because of his family, community, and personal desire? The Joker was a failed comedian, forced into a life of crime, to support his pregnant wife. Was the desire to kill always in Dexter, or was it created in the murder of his mother, and supported by his father, a cop, a way to channel his “dark passenger” in order to do something “good” with his violent tendencies?

This is how you can get people to empathize or sympathize. These people weren’t always this way. They had to do it, for some reason. And then along the way, you have the opportunity to let them redeem themselves, to change. It doesn’t always happen, sometimes the monster is just going to feed. There is no stopping a Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees, Pennywise, Satan, or Cthulhu. (Or is there?)

Shades of Gray

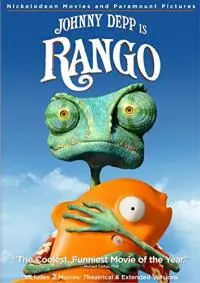

In any short story you have to have change, otherwise, you have a vignette. Typically it’s about your protagonist—their inciting incident, their internal and external conflicts, leading to a climax, resolution (change), and denouement (understanding). But this can also happen with your bad guys, your villains, your monsters. I think of the role that The Weaver played in the aforementioned Perdido Street Station; I think of how the Terminator went from evil robot to helpful friend; I think of Rattlesnake Jake at the end of Rango. Part of what makes the journey of your hero so interesting, is that there are so many opportunities to change, to do better (or worse), to save the day, or fall victim to your base desires, and selfish needs. Very few villains are entirely evil, 100% black, no room for any sort of sympathy, understanding, or change. Likewise, very few heroes are perfect, never failing, always doing the right thing, never having a moment of weakness.

In any short story you have to have change, otherwise, you have a vignette. Typically it’s about your protagonist—their inciting incident, their internal and external conflicts, leading to a climax, resolution (change), and denouement (understanding). But this can also happen with your bad guys, your villains, your monsters. I think of the role that The Weaver played in the aforementioned Perdido Street Station; I think of how the Terminator went from evil robot to helpful friend; I think of Rattlesnake Jake at the end of Rango. Part of what makes the journey of your hero so interesting, is that there are so many opportunities to change, to do better (or worse), to save the day, or fall victim to your base desires, and selfish needs. Very few villains are entirely evil, 100% black, no room for any sort of sympathy, understanding, or change. Likewise, very few heroes are perfect, never failing, always doing the right thing, never having a moment of weakness.

Where does Batman land on this black to white spectrum? What about Superman, especially the darker stories (e.g., Drunk Superman)? What about Dexter? And how is it that somehow I find Hannibal Lecter worthy of my support? Am I just fascinated by his personality, by his helping Clarice, or is there something else going on there? And we have to admit, sometimes vengeance can be rather satisfying. Isn’t that what we feel when we cheer on these characters as they save Gotham, kill the serial killers, and other (sometimes) questionable acts? Shades of gray, for sure.

In Conclusion

At the end of the day, what I’m saying here is that you need to have as much depth in your bad guys, as you do in your good guys. Your protagonist—whether they are a lovable superhero or a flawed, unlikable mercenary—is going to get your attention as an author. You’re going to go deep into their origin story, their conflicts (internal and external) and work toward the situations at hand to change, to save the world, while quieting their inner demons. But you also need to put just as much work into your villains, your antagonists, your bad guys. If you make them one note, they aren’t going to resonate, there is less chance you will truly scare us, keep us awake at night, and get under our skin. So dig deep, study the human condition (or whatever you’re creating) and get us to care, so that we can feel strong emotions, thus making the journey worthwhile.

Get Perdido Street Station at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.