If you think the only hook to your story or novel is the first line, then boy do I have some news for you. In order to engage the reader you need to hook them not just once, but as many times as you can, so there is no way they can escape. How do you do that? It starts with the title, and then expands to the first line, the first paragraph, the first page, the first scene, and the first chapter (if writing a novel). Let’s get into this, so we can figure out how best to hook YOUR readers, no matter what genre or style you might have.

The Title

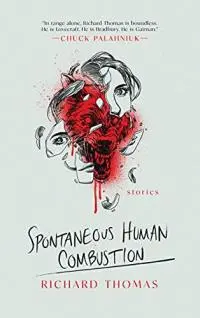

That’s right, it all starts with the title. And yes, I’m quite aware that my first three novels were titled Transubstantiate, Disintegration, and Breaker. (At least it wasn’t It.) But my short story collections were a bit more interesting—Herniated Roots, Staring Into the Abyss, Tribulations, and Spontaneous Human Combustion (out on 2/22/22 with Turner Publishing). Let me unpack these titles a little bit before I move onto short stories

- Transubstantiate–a fancy word for change, that also has religious connotations. At least the word is a little strange, not used all the time in everyday conversations.

- Disintegration–everything in this book is falling apart, with our unnamed protagonist. So the theme of disintegration runs through the book.

- Breaker—he is a fighter, so he breaks people, but it’s also about breaking the cycle of abuse. Is a serial killer born or made? That’s the question I’m asking.

- Herniated Roots—this comes from a title of one of the stories in the collection, and it’s a compelling visual, IMO. It implies violence, and weirdness.

- Staring Into the Abyss—part of a Nietzsche quote, which talks about how you shouldn’t battle with monsters, “lest ye become a monster, for when you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back into you.” This hints at the themes of this collection really well, I think.

- Spontaneous Human Combustion—the tricky part here is that I’m not so much talking about the combustion part, the fire, but the human combustion, what it means to be less (or more) than human, what happens when we lose our humanity.

And as far as my short story titles, what are some of my favorites? I have a few:

- “The Caged Bird Sings in a Darkness of Its Own Creation”—this story is so weird, but I like the idea of a creature building its own prison, a cage made out of darkness, so this really sets the tone early. Maya Angelou’s autobiography was called I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which may have been part of the inspiration for this title.

- I also went through a phase where I had several titles that came from the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows—“Hiraeth,” “Nodus Tollens,” and “Saudade.” I don’t know if people went and looked these words up, but if they did, they definitely got a bit more information about what was coming. Hiraeth means “a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return, a home which never was; the nostalgia, the yearning, the grief for the lost places of your past.” Quite a lot, right? Of course, if people don’t look these words up or don’t know what they mean, I guess that I do lose out. But that’s the risk you take.

- “In His House” is a direct reference to a Lovecraftian phrase, “In his house at R’lyeh dead Cthulhu waits dreaming.”

So you can see how the title is supposed to hint at what’s coming without giving it all away. It’s the tip of the spear, shoved into the tip of the iceberg. It’s the very first thing people read—so have fun with it, be clever, and see where it might go.

The First Line

This is where most people think the story or novel starts. And it really is pretty important. You can look at Fahrenheit 451, with “It was a pleasure to burn,” or Stephen King’s first book in The Dark Tower series, The Gunslinger, which begins, “The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.” This line, the first line, should set the tone, hint at the internal and external conflicts, and help to create a sense of urgency and stakes. Look at your stories and novels, hell, pick up your favorite short story or collection or novel and see how the experts do it. It’s definitely something you have to work on, it takes practice, and not everyone is good at it. I’ll list a few of mine below:

- “When the red sea of rage washes over me, I picture a house on a hill, far away from the rest of the world, a band of oak trees around it, full of greenery, a singular whisper of smoke drifting up into the sky—a place where nobody will get hurt.” (Sets the tone and vibe.) From “Battle Not With Monsters.”

- “Rebecca hated her father for what he’d done, refusing to help him dig the grave, arms crossed, tears running down her face, the body under the tarp no longer Grandpa, no more secret conversations when they were alone, just the two of them now—her father the killer, her father and his constant worries, her father convinced that the old man had finally fallen sick.” (Long sentence, right? A lot going on here.) From “Little Red Wagon.”

- “If you drive north, away from the city and bright lights, up toward the cornfields, and then on beyond into the darkness of the forests that thicken as it grows colder, you will find some semblance of a man living in a dilapidated house at the end of a long, gravel road.” (This hints at a lot.) From “The Keeper of the Light.”

- “The first sensation I feel when I come to is a thrumming in my legs, so I must be alive.” (A short one! And waking up, how bold.) From “Open Waters.”

The First Paragraph

Some of you may be paragraph hookers (yes, that’s a thing), and that’s okay, because while the title and first line are important, the first two hooks, the supporting paragraph can either be the hook or it can expand upon the first line to build out your story. Whatever you put in the first paragraph, it better be important. By showing this to us, you are SAYING that it’s important, “Hey, look here, this is first, this is crucial.” So make sure that’s true. Here are a couple of my paragraph hooks—openings that may have a good first line, but really are trying to grab you with what the first couple of lines set up here.

- “I’ve been trying to find myself for what seems my whole life. Now, a dark fate has found me instead. I’ve summoned something; drawn its gaze down upon me. This is how the suffering begins.” (Good first line, then the dark fate, then something summoned, and finally the suffering. I’m trying to hook you in several ways.) From “Nodus Tollens.”

- “In the process of losing my mind, the rest of the world has fallen away. A cloud hangs over the monotone house, the grass growing longer, the litter outside caught in the wild blades of fading green, as the shadows inside play games with me. I used to resist them, tried to shine a light into the corners of the living room, the drapes—the long hallways that never seemed to end. I used to scream at them, crying as I fell to my knees, begging to be left alone. When I walk by the bedroom now, the door closed, a cold wave pushing out from under the gaps, nipping at my ankles, I moan quietly under my breath as a shadow flickers at the doorframe. I do not open it, not now.” (Right away we establish that the protagonist is not mentally stable. So everything that follows has to be questioned—the house, the shadows, the wave of coldness, flickering images, and the element of time, NOT NOW. This should set up the tone and atmosphere, as well as hint at what’s coming.) From “Surrender.”

- “Darkness spilled over the land. Ten locks were fastened, turned, and keyed as fast as his ruddy hands could move. If you fell asleep with the pale sunshine drifting down on your face, you could wake up in a room full of strange men with a gun in your mouth. He shook the door handle several times, satisfied that it was indeed locked.” (This hints at a bigger story, paranoia, and fear.) From my first professional sale, “Stillness.”

The First Page

What you do with the first page of your story or novel is crucial to keeping your reader’s attention. You have hooked us with the title, first line, and first paragraph, and now you must go deeper. You want to further establish both the internal and external conflicts, you want to build this world you have created (especially if it’s entirely made up, like in fantasy), you want to set things in motion, show us how this is all part of the inciting incident (that moment in time after which things will never be the same). You need to start increasing the tension, show us the stakes and sense of urgency that belies this opening. You need to go deeper into the setting, so you can ground this narrative, while showing your main character/s, using sensory detail to enhance the mood. Whatever threads you started, you need to continue.

![]() The First Scene

The First Scene

Now, your short story may not even have more than one scene. My tale, “Undone,” is 1,501 words, and it’s one sentence, so there are no scene breaks. But I assume that most of your stories will have multiples scenes—maybe as few as three, or as many as ten—it’s really up to you; it depends on the genre and voice of your story. And if you are writing a novel, maybe you will only have chapters, so there might not be any scene breaks within each chapter, but then again, maybe there will. My current novel in progress is entitled Incarnate, and there are three acts, with each act consisting of six chapters, and each chapter has about three or four scene breaks (typically), adding up to about 4,000 words per chapter. But what you want to think about with the first scene is all of the Freytag stuff you’re doing on a larger scale with the entire story (or novel). You want to hook us, set this up, address the conflicts, and then increase the tension, building to a smaller climax, where something needs to change and/or be revealed, keeping the pages turning, as we set up the next scene. It’s not easy.

The First Chapter

For those working on a book, each chapter is an organized collection of elements, that’s why it’s a chapter. Maybe it’s a long drive out into the country to visit a haunted house—one chapter. Maybe it’s the origin story of a monstrous beast—one chapter. Maybe it’s showing how your protagonist does his thing—magic, or ritual, or dark act—unpacked in great detail over several thousand words. Maybe your journey is across the country, and each chapter is a day. Maybe it’s a shifting POV, your novel having several different main characters, each with their own story and perspective. However you organize it, you want to hook us, build it up, and then end each chapter with a BANG. I can’t think of a better example for the ins and outs of chapters than Josh Malerman’s Bird Box. He is the master of transition, revealing secrets at the end of each chapter, dropping bombs, and then shifting over to the alternate timeline, as we wait to see how these two narratives will come crashing together in the end.

In Conclusion

So when it comes to your story, or novel, find a way to connect your title, your first line (grabbing us from the jump), as you expand your key elements across the first paragraph, those elements essential to the narrative. No red herrings here! And then across the first page, build out your world, ground your story, show us your character/s, and help us to create the atmosphere of your genre and tale. Continue that all the way through your first scene, and if you have a book, the first chapter. With stories, it’s crucial to grab us and never let go, knowing you may only have 5,000 words to tell your story (or less). For books, understand that agents and presses quite often are looking only at the first few pages—maybe ten, maybe fifty—and trying to decide if they want to keep reading, or sign you. They are looking for reasons to say yes, but they are also looking for reasons to say no. Don’t let them find that negative response—hook them with every trick and emotion and compelling image you can find—and then never let them go. Your workshop cohorts, your peers, your readers, an agent, and a press—they all want to be hooked, so make sure it’s a big, nasty multi-pronged bastard that plunges deep into their flesh.

Get Spontaneous Human Combustion at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.

The First Scene

The First Scene