Over the years I’ve noticed that my students sometimes break their stories in strange places, so I thought I’d write up my thoughts on when, where, how, and why to insert scene breaks into your stories.

NEVER

There may actually be some instances where you don’t have a scene break, so I wanted to get that out of the way first. I’ve written many flash fiction stories—whether they were 100 words, 500 words, or 1,000 words—where I had no breaks at all. I still incorporated all of the Freytag stuff—hook, inciting incident, exposition, internal and external conflict, rising tension, climax, resolution, change, and denouement—but sometimes there wasn’t a break. I’ve also done this with longer work, whether it was the 2,000-word epistolary Lovecratian story “In His House” or the 1,501-word “Undone” that was one sentence. If your story is in one place, in one moment of time, you may be able to get away with not having a break. And that is totally okay.

WHEN THERE IS A TIME SHIFT

The easiest way to break a scene is at a shift in time. This to me is pretty much mandatory in your stories. I can’t think of a reason why you wouldn’t put a scene break here. It could be a matter of your character going to sleep, waking up in the next scene. It could be a matter of ending a plot point or important scene, and then leaping forward 100 years. It could be that you are in a moment of time in 2021 and then the next scene is a flashback to 1801, and then the following scene is back to the present in 2021. All of these sound like scene breaks to me.

WHEN THE LOCATION CHANGES

Another great place to add a scene break is when you change locations. You start the scene at home, and then drive to work, something is revealed, and as we contemplate that—the scene ends. Or it can be more of a leap, where we track the time your character spends on Mars, then Earth, then Jupiter—each break a different location.

![]() WHEN THERE IS A POV SHIFT

WHEN THERE IS A POV SHIFT

This is another easy one, IMO. Now, most short stories probably have one protagonist, and one POV, so you may not need to address that, but if you have 2-3 perspectives, if you’re weaving multiple stories here, that to me definitely requires a scene break. Most of my stories have one protagonist, but I can think of a few that had more than one, such as my Rashomon story, “Dyer,” or “The Caged Bird Sings in a Darkness of Its Own Creation.”

AT AN IMPORTANT MOMENT

This one is harder to do, but a great way to end a scene is to insert a break when we have a major plot point, lesson learned, or bit of information dropped. You create a mini cliffhanger, and then the reader wants to push forward to see what happens next. Can this moment happen with the scene continuing immediately after? Sure. But most likely when you drop this bomb, you will move on to a moment in time minutes, hours, days, or weeks later.

WHEN SKIPPING AHEAD

Quite often we have some mundane things that need to happen, but they don’t need to happen on the page. The character is going to build a dollhouse for their daughter, they’ve gathered everything they need, they are going to insert magic (or witchy items) into the building process, but it’s going to take hours, maybe days. Do we need to see all of this? Maybe, maybe not. Some, most likely. But at some point (much like that scene in Perdido Street Station, you all know the one I’m talking about, with the cables) we’re going to get sick of the gluing and painting and building. Skip forward. Don’t show us the boring drive to work. Don’t show us the meal preparation. Don’t show us the guy doing his taxes. We get it.

WHEN MAKING LISTS OR REPEATING ELEMENTS

I’ve read quite a few list stories and they all had scene breaks when they listed a new item. For those kinds of stories, you might not insert a glyph, but you may insert a new title or sub-head. I’m thinking of stories where you have many different examples of the theme, such as “The Apartment Dwellers Bestiary” by Kij Johnson or “Justice Systems in Quantum Parallel Probabilities” by Lettie Prell. In Kij’s story, each entry is a listing of a different apartment dweller, and that’s how the scenes are broken. In Lettie’s story, each example is of another justice system, and that triggers a scene break.

TO CREATE TENSION

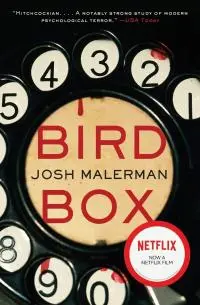

For those of you who have read Bird Box, you know how masterfully Josh Malerman broke up his chapters, shifting in time from the present, to the past, and back. Chapter breaks and scene breaks are essentially the same thing. The tension he created in dropping information, then shifting away, having something tense happen (creatures, wolves, man on the river, etc.), and then delaying its resolution by flipping over to the other timeline—brilliant. Same thing with your stories. Now obviously that’s harder to do in flash, or even in a story at 3,000 words, but if you have tension, and enough going on, with multiple scene breaks, this is a great way to increase your tension, force the reader to sit in that place for a while, and delay the resolution, or horror that comes next.

WHEN SHOULD YOU NOT INSERT A BREAK?

And then of course, we have to discuss when NOT to insert a scene break. Don’t just break a story because you’ve written a certain amount of words. If you hit 500 words and feel like it’s time to break the story, make sure you have a good reason to do that. Really, every scene break (just like every chapter of a book) should be a smaller Freytag arc. In a novel you have the arc of the book, the arc of sections (Part One, Part Two, Part Three), the arc of chapters, and the arc of scene breaks within a chapter. Do not insert a scene break where nothing major happens, and then continue with the next sentence picking up right where you left off. I’ve seen this happen way more than it should. Really, what you’re looking for is one of the previous points I’ve made, otherwise, keep going until you hit a moment where it demands a scene break.

IN CONCLUSION

When you are writing your stories, make sure that you insert scene breaks when they are needed, at the appropriate moment. Turns out you may not need one at all! But most likely you’ll have several in your short stories, triggered by one of the following moments: a time shift, a location change, a POV shift, an important revelation, a desire to skip ahead over more mundane events, when making lists or repeating elements, or to create and intensify tension. Be purposeful in your scene breaks, and it will add to the reading experience.

Get Perdido Street Station at Bookshop or Amazon

Get Bird Box at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.

WHEN THERE IS A POV SHIFT

WHEN THERE IS A POV SHIFT