This week I’ll be dissecting another of my stories, “Fireflies.” It was originally published in Polluto and later online at Circa Review. It’s been a while since I did this, and I’m excited to dig into this story for a number of reasons. First, this was one of my first attempts to write magical realism. It was also one of my first attempts in recent memory to write a short story that had a positive core, a center that was built around love, romance, and nostalgia. I also wanted to try and write a story that was set in the future, but had an “old world” feeling, as an experiment. I am trying to turn this story (and “Flowers for Jessica” as well as “Playing With Fire”) into my third novel, Incarnate. And finally, because it’s a story of mine I really like, I’m curious to go back and read it again, see how it holds up. The entire story is listed below, for your convenience, but it’s not long, about 1,700 words.

Oh, I should also mention that I originally wrote this for an anthology, Machine of Death (Volume 2). So there was a certain prompt, or idea that it was based around—a slip of paper that would predict your death, and the title of the story HAD to be the cause of death (in this case, yes, fireflies). I did not get into that anthology, sadly. I hope you enjoy my thoughts on this story, as well as reading it—for the first time, or perhaps, again.

FIREFLIES

When the winds come, the hut shakes and I grab the tabletop, the heavy wood carved centuries ago, scarred and pitted by time. I wait for the roof to rip off, exposing me to some giant hand, pulling me into the sky to be punished for my sins. The beams creak and moan, and in the gaps I hear her voice. I beg her to shut up, to leave me alone, but the dull ache that wraps around my plodding heart, it trembles and hesitates, apologizes for snapping at her, my love, and asks her for forgiveness. And she gives it, freely.

The scrap of paper dances in the wooden bowl, the printed type from another time, so long ago, when machines still ruled the world. It nestles into the handful of buckeyes, their dull red orbs rolling around—a fluttering eagle feather next to the pink fleshy lining of an aging conch shell. I’ve memorized the serial number that runs along the bottom, the bent edges of the stained slip, once a shiny white stock, now a dull, faded yellow. The solitary word used to make me laugh. Isabella and I would dance in their glow, mocking the insects, asking them to take us home—to smother us in their amber. I don’t laugh about them anymore.

After the winds start up it isn’t long until the black rain beats down upon the tin roof, sheets of metal scraps stolen from ruptured airplanes that dot the island, bent and fastened by my tired, mangled hands. When the door swings open, I’m not surprised—the latch has been busted for days now, and my hope was that it would fix itself, the wood warped and swollen, praying for the doorframe to shift back to its former self. Shadows drift in from the field, lightning fracturing the night. The long grass bends, rippling in the flash of light, photos taken as her arms raise and lower, long legs extended, leaping, and I shake my head, squint my eyes shut, and beg for more time. Not tonight. I’m too fragile to handle the haunting.

And then it is quiet. She is gone, my memory of her body, her giving curves and gentle fingers fading into the night. Beyond the field lies the edge of the cliff, and beyond that is the water of a never-ending ocean, black as tar, a universe expanding, calling me to take the long swim home.

At the edges there is a history, a blur of wagons and horses, bodies piled high, the stench taking on a physical weight, splintered doors slamming shut like gunshots as the dead were taken away. She was taken away, and for nothing more than a ripe peach hanging from an abandoned tree, the orchard ripe with flies and decaying nectar. But the disease had taken hold already, whatever we called the mutation then, the plague had come home to roost, to rest—to unfold.

“Isabella,” I sigh, a wave of moonlight crossing the field, crawling over the lush grass, wandering inside the hut. I light the candles that sit in a melted pile, now that the winds have died down. The box of matches is running low, a trip to the town square near at hand.

The howling will start soon, the rabid pack of mongrels coming to sniff at the cracks of my homestead, licking at the sap that plugs the gaps, snuffling at the door, rattling the frame with their dark, wet snouts, pissing on it and moving on in a sickening mass of dark, hairy flesh. There is little time to fix the latch, but I must.

On the wall hang a few handmade instruments—bent metal and wood stained with the slick oil of my flesh. I am not a blacksmith nor am I a carpenter. These tools are about all I have. Heavy rocks work just as well and sometimes I get lucky in the wreckage, a steel beam or bar changing the way that my life staggers on. So many times I’ve frayed the flesh of my fingers just to steal a bolt or two, a handful of nuts and nails taken from the bent and empty metal birds. And to what end? In a few days when I’m drained by the sunlight that beats down on this solitary rock, the heat will push me down until I collapse in the sand on the east side of the island, seashells spilling from my hands. Or the exhaustion will leave me in the meadow, covered in tiny cuts from the sharp blades of grass that surround me, lost to time and place. The black winged beasts will descend on my homestead, pecking at the shiny objects, these diseased children of the raven and magpie. The dogs will take what is left, I don’t know why, scattering the bits of metal far and wide, the dull pieces of steel picked up by the deformed rodents that live in the caves down by the water. They mock me. But I continue. She tells me to carry on.

I take down the bastard screwdriver and malformed hammer and push at the lock that protrudes from the door, trying to straighten it out, to solidify this pitiful lock, so that the demon beasts will not get in tonight.

The wind picks up again as I crouch in the doorway, the coolness washing over my slick skin, and the grass waves back and forth, telling me to come lay down in the damp finery of their offerings, and for a moment, I stop and consider doing just that.

No. The latch.

I lick my lips and bend the piece of metal, the rusted tongue eluding my clumsy fingers, the metal in my hand slipping, running a gash through my left hand. I shove my palm into my mouth, cursing as I sup the liquid, knowing that it will surely draw them out. And at the edge of the field there is a flickering of lights, dots of yellow fading in and out—they’ve smelled the humanity that drips onto the stone porch, the slab of grey rock dotted with discs of red and I hurry to bend the metal straight.

To my left the glowing circles meander across the night sky, taking their time. They have all night to play with me and I have nowhere to go. My eyes stay on them, watching as they pulse in and out, slowly moving across the field, the cool metal in my hands finally bending. I check my work, lifting the latch up and down, my eyes drawn back to the field and to my handiwork. I step inside and close the door, their night music fading behind the dense wood. Sliding the lock in place, I tug on the brass knob and it holds, it is solid, and the shadows pour over the edge of the cliff, stretching and shrinking, eager to test my work. I rattle the knob one more time.

I sit down at the table, the old wooden chair creaking under my weight, as the panic drains out of my skin, my face falling into my open hands, muffling a sob that has been building all day.

“Oh, Isabelle,” I moan. “Help me, my love.”

I can hear them circling the house, their hot rancid breath coming out in gasps, the wet lapping of their tongues in the air, teeth clicking, snapping at each other as their hackles raise and a heavy wind pushes against the house. I don’t want to blow out the candles—they give me comfort and warmth. I’ve only just lit them with my dwindling supply of matches—but I do it anyway.

“Go away,” I yell, and they yip and bark, excited by my anger, hoping to lure me outside, wanting the confrontation—willing me to take them on tonight. I hear a clang of metal on the slab outside and creep over to look between the cracks. A body slams against the door and I fall backwards, my heart stuttering, a long bit of rusted rebar lying on the rock like a sacrifice. I smile against all logic. I grin in the darkness despite my need to piss, my stomach rolling and unfurling—they want me to take this weapon, they’re trying to even up the odds. Manipulative bastards.

Another heavy weight is flung against the door and I worry the latch will not hold. There is a sharp cry and the furry beasts move away from the front of the hut, and I hear the animals disappear behind the house. A gathering of yellow lights hovers in front of the door, and this may be my only chance tonight. I flick the metal latch up and step forward, flipping my head to the left and then the right, the wind gusting, grasses sighing, and I bend over to pick up the bar. The glowing dots gather before me and I stand upright as they fill the frame of my Isabella, just for a moment, her curves and slender legs, her long hair blowing in the darkness, and then they break apart. I take a step outside.

The fireflies head back across the grassy field, a line of yellow dots, expanding into slashes, and I follow this lost highway out into the night, a wave of peaceful inevitability washing over me, the hounds coming back around to the front, yapping at me, nipping at my feet, my knees, as they bound in and out of the grasses. I swing the bar lazily towards them, and they retreat. Moments later they are back at my side, escorting me through the lapping blades. I fling the bar out into the grass and it lands with a dull thud, the animals descending on it, confused. They sniff at the metal, something off, standing still now, and they let me continue, rotting flesh that I am—they let me go.

When the blinking lights drift out over the water and up into the sky, I follow them. She whispers in my ear, her mouth on my neck, and the tears come, the dancing lights pulling me over. Her laughter is with me and I take it, I hold it, and let it cushion me as I fall to embrace the rocks below.

DISSECTION

When the winds come, the hut shakes and I grab the tabletop, the heavy wood carved centuries ago, scarred and pitted by time. I wait for the roof to rip off, exposing me to some giant hand, pulling me into the sky to be punished for my sins. The beams creak and moan, and in the gaps I hear her voice. I beg her to shut up, to leave me alone, but the dull ache that wraps around my plodding heart, it trembles and hesitates, apologizes for snapping at her, my love, and asks her for forgiveness. And she gives it, freely.

That opening line is a decent hook. I wanted to convey a sense of time. But I was really hoping that my entire first paragraph would be my hook—and that’s okay, taking that much time. I know I always lecture authors on their narrative hook, but it can be more than just one sentence. It can be two, even up to the first paragraph, some even say the first page, the first chapter, all expanding moments, hooks that are trying to sink into your reader and grab hold. The inclusion of giant hands is on purpose, to try and create that idea of magic, mythology—the first instance of me trying to write something fantastic, surreal or magical. At the end of this paragraph I’m banking on the fact that the wind, the voice, his love—that all of those seeds I’m planting will be enough of a hook. What’s going on? Is she real or imagined? What next? If I’ve done my job right, you’ll be eager to keep reading. What do you think, how did I do here?

The scrap of paper dances in the wooden bowl, the printed type from another time, so long ago, when machines still ruled the world. It nestles into the handful of buckeyes, their dull red orbs rolling around—a fluttering eagle feather next to the pink fleshy lining of an aging conch shell. I’ve memorized the serial number that runs along the bottom, the bent edges of the stained slip, once a shiny white stock, now a dull, faded yellow. The solitary word used to make me laugh. Isabella and I would dance in their glow, mocking the insects, asking them to take us home—to smother us in their amber. I don’t laugh about them anymore.

This is my prompt from that contest—the slip of paper, the machine of death. What I wanted to do was immediately follow that technology with nature, the buckeyes, eagle feather, and conch shell. Then back to the serial number, the technology, and more allusions to time. My first clue about what is to come (besides the title) is when I mention the “solitary word” and how it made them laugh, these lovers, the idea that a firefly would be his demise. Her name, Isabella, is uttered for the first time. I use the words “smother” and “mocking” on purpose. Normally you wouldn’t imagine a firefly as an ominous insect, but I wanted to hint at that early on. He then says that he doesn’t “laugh about them anymore,” further hinting at something dark.

Side note: this is personal, but I wanted to mention this. My wife and I had a miscarriage once, after our twins were born, several years later, one of those pregnancies that surprise you. She was on the pill. Neither of us were prepared, and it was a strange time. Once we got over the shock, we embraced the idea of starting over again, back to diapers, a third child when we had only prepared for two. It had taken me a few weeks to get to that place. My wife knew it was going to be a girl. We were going to call her Isabella. Then she miscarried. You may have noticed I’ve used that name a few times in my stories. It’s my way of honoring that memory, that baby, and to remind myself to not question and mourn change, but to embrace it, or suffer the consequences. It’s a heavy weight that rests on my heart, but one that I try to own, by turning my loss into his loss, that of his lover, Isabella.

After the winds start up it isn’t long until the black rain beats down upon the tin roof, sheets of metal scraps stolen from ruptured airplanes that dot the island, bent and fastened by my tired, mangled hands. When the door swings open, I’m not surprised—the latch has been busted for days now, and my hope was that it would fix itself, the wood warped and swollen, praying for the doorframe to shift back to its former self. Shadows drift in from the field, lightning fracturing the night. The long grass bends, rippling in the flash of light, photos taken as her arms raise and lower, long legs extended, leaping, and I shake my head, squint my eyes shut, and beg for more time. Not tonight. I’m too fragile to handle the haunting.

With the plane we get civilization, but something lost, a downed airplane. We get his handiwork, the idea that he built this hut by himself, with his bare hands. The words “warped” and “swollen” hint at something more, assigning human traits to inanimate objects. We see a hint of Isabella here in the flashes of light, his fragile state—a haunting. This is all going towards atmosphere. It also hints at his conflict (remember how I always talk about conflict and resolution) where he wants his wife, but feels haunted, something is not right—how can he resolve this?

And then it is quiet. She is gone, my memory of her body, her giving curves and gentle fingers fading into the night. Beyond the field lies the edge of the cliff, and beyond that is the water of a never-ending ocean, black as tar, a universe expanding, calling me to take the long swim home.

There is just a bit of sex here with her curves and fingers, but more importantly, here, and in the previous paragraph, I’m painting a picture of the land—hut, tall grass, and then the edge of a cliff, and beyond that water. You can (hopefully) see all of that. The “long swim home” is a reference to death, to his thoughts of a possible suicide, the first time we really see how desperate he is.

At the edges there is a history, a blur of wagons and horses, bodies piled high, the stench taking on a physical weight, splintered doors slamming shut like gunshots as the dead were taken away. She was taken away, and for nothing more than a ripe peach hanging from an abandoned tree, the orchard ripe with flies and decaying nectar. But the disease had taken hold already, whatever we called the mutation then, the plague had come home to roost, to rest—to unfold.

“Isabella,” I sigh, a wave of moonlight crossing the field, crawling over the lush grass, wandering inside the hut. I light the candles that sit in a melted pile, now that the winds have died down. The box of matches is running low, a trip to the town square near at hand.

This was an important moment to me. Here we read about how the world fell apart, how his Isabella died. I wanted that mixture of a simple life (wagons, horses) paired with something more current (mutation, the technology we know existed, the machines) as well as a hint of nature, and magic (the peach). Obviously, fruits in trees that hurt or kill you, those are references to the Garden of Eden, to Adam and Eve. I mention the lack of supplies, his matches, and a trip into town, so you can see what his life is like, his rituals, what he does to stay alive. I want you by now to feel a little sorry for him, his loss, and to see that he is trying to stay alive—he hasn’t given up yet. Do you care yet? Do you feel sympathy, empathy?

The howling will start soon, the rabid pack of mongrels coming to sniff at the cracks of my homestead, licking at the sap that plugs the gaps, snuffling at the door, rattling the frame with their dark, wet snouts, pissing on it and moving on in a sickening mass of dark, hairy flesh. There is little time to fix the latch, but I must.

I knew I wanted wolves in this story. They are mythological, they are similar to dogs so they aren’t inherently evil, and they also represent danger in so many fairy tales and fables. I wanted that sense of story, of history. It was important that I show them, their physical attributes, sniffing and licking, the way they mark their territory by pissing on it, so you can picture them, the way they move and act. The plugs of sap again show how his world is now, how he makes things. And it ends with fixing that latch—the first real push for tension. The wolves are coming, and he has to fix that latch.

On the wall hang a few handmade instruments—bent metal and wood stained with the slick oil of my flesh. I am not a blacksmith nor am I a carpenter. These tools are about all I have. Heavy rocks work just as well and sometimes I get lucky in the wreckage, a steel beam or bar changing the way that my life staggers on. So many times I’ve frayed the flesh of my fingers just to steal a bolt or two, a handful of nuts and nails taken from the bent and empty metal birds. And to what end? In a few days when I’m drained by the sunlight that beats down on this solitary rock, the heat will push me down until I collapse in the sand on the east side of the island, seashells spilling from my hands. Or the exhaustion will leave me in the meadow, covered in tiny cuts from the sharp blades of grass that surround me, lost to time and place. The black winged beasts will descend on my homestead, pecking at the shiny objects, these diseased children of the raven and magpie. The dogs will take what is left, I don’t know why, scattering the bits of metal far and wide, the dull pieces of steel picked up by the deformed rodents that live in the caves down by the water. They mock me. But I continue. She tells me to carry on.

I really wanted to unpack this hut, show you how he lived, the simplicity of his life, the ways he has to fight to survive. How can you hate somebody that makes tools out of scraps? Again I show you how his days unfold—rummaging for scraps in the daylight, flaying his fingers, just for a bolt or piece of metal. I expand the island to include the beach—did you know it was an island or just that there was water near? Not sure if I did that well enough. Even though I used the word in the third paragraph, did that sink in? Does it matter? In the end it does, because he can’t run away. He is trapped. Even the grass blades cut at him—I’m now repeating the idea that this island may be hostile. It ends with the plea from Isabella to “carry on.” She doesn’t want him to join her, to kill himself. So, is she haunting him or protecting him? We aren’t sure.

I take down the bastard screwdriver and malformed hammer and push at the lock that protrudes from the door, trying to straighten it out, to solidify this pitiful lock, so that the demon beasts will not get in tonight.

The wind picks up again as I crouch in the doorway, the coolness washing over my slick skin, and the grass waves back and forth, telling me to come lay down in the damp finery of their offerings, and for a moment, I stop and consider doing just that.

No. The latch.

I lick my lips and bend the piece of metal, the rusted tongue eluding my clumsy fingers, the metal in my hand slipping, running a gash through my left hand. I shove my palm into my mouth, cursing as I sup the liquid, knowing that it will surely draw them out. And at the edge of the field there is a flickering of lights, dots of yellow fading in and out—they’ve smelled the humanity that drips onto the stone porch, the slab of grey rock dotted with discs of red and I hurry to bend the metal straight.

Here is where I start to pump up the tension. I want things to unfold, for time to pass quickly to show him rushing, struggling to fix that damn latch. So how do I slow him down, handicap him? He runs the screwdriver into his hand. But the blood draws out the creatures of the island—the flickering lights, and the wolves, as drops of blood fall to the stone.

To my left the glowing circles meander across the night sky, taking their time. They have all night to play with me and I have nowhere to go. My eyes stay on them, watching as they pulse in and out, slowly moving across the field, the cool metal in my hands finally bending. I check my work, lifting the latch up and down, my eyes drawn back to the field and to my handiwork. I step inside and close the door, their night music fading behind the dense wood. Sliding the lock in place, I tug on the brass knob and it holds, it is solid, and the shadows pour over the edge of the cliff, stretching and shrinking, eager to test my work. I rattle the knob one more time.

I sit down at the table, the old wooden chair creaking under my weight, as the panic drains out of my skin, my face falling into my open hands, muffling a sob that has been building all day.

“Oh, Isabelle,” I moan. “Help me, my love.”

The first paragraph here is hopefully making you, the reader, very tense. The lights are moving, as the shadows pour over the edge of the cliff, the wolves. He sits down, but still afraid. I mean, how strong IS that latch, after all? He has drawn the lights, the wolves to him, not what he meant to do.

I can hear them circling the house, their hot rancid breath coming out in gasps, the wet lapping of their tongues in the air, teeth clicking, snapping at each other as their hackles raise and a heavy wind pushes against the house. I don’t want to blow out the candles—they give me comfort and warmth. I’ve only just lit them with my dwindling supply of matches—but I do it anyway.

“Go away,” I yell, and they yip and bark, excited by my anger, hoping to lure me outside, wanting the confrontation—willing me to take them on tonight. I hear a clang of metal on the slab outside and creep over to look between the cracks. A body slams against the door and I fall backwards, my heart stuttering, a long bit of rusted rebar lying on the rock like a sacrifice. I smile against all logic. I grin in the darkness despite my need to piss, my stomach rolling and unfurling—they want me to take this weapon, they’re trying to even up the odds. Manipulative bastards.

Another heavy weight is flung against the door and I worry the latch will not hold. There is a sharp cry and the furry beasts move away from the front of the hut, and I hear the animals disappear behind the house. A gathering of yellow lights hovers in front of the door, and this may be my only chance tonight. I flick the metal latch up and step forward, flipping my head to the left and then the right, the wind gusting, grasses sighing, and I bend over to pick up the bar. The glowing dots gather before me and I stand upright as they fill the frame of my Isabella, just for a moment, her curves and slender legs, her long hair blowing in the darkness, and then they break apart. I take a step outside.

Here is where we see how good his work is—will it hold up? I wanted as many details about the wolves as I could imagine—teeth clacking, hot breath. And then he blows out the candle, sending himself into the darkness. What a frightening idea, yeah? Who would have that courage? I take a chance that you’ll allow me to see through the door, to see the piece of rebar, that you’ll believe he knows what they’ve dropped—either by the sound of it, or maybe the idea that this happens all the time, the wolves trying to lure him out. He can see bits of the wolves and lights between the cracks in the wood, and like in many horror movies, I make him step outside. The fireflies form the shape of his dead love, and he follows them. I’m hoping here you are upset, that you are worried he will get torn to shreds.

The fireflies head back across the grassy field, a line of yellow dots, expanding into slashes, and I follow this lost highway out into the night, a wave of peaceful inevitability washing over me, the hounds coming back around to the front, yapping at me, nipping at my feet, my knees, as they bound in and out of the grasses. I swing the bar lazily towards them, and they retreat. Moments later they are back at my side, escorting me through the lapping blades. I fling the bar out into the grass and it lands with a dull thud, the animals descending on it, confused. They sniff at the metal, something off, standing still now, and they let me continue, rotting flesh that I am—they let me go.

He is in a trance of sorts here, as the wolves come back around the house. What do you expect to happen? Will they bite him—chew him up? Did you expect them to drop back and merely escort him forward? What is happening? They let the rotten flesh go.

When the blinking lights drift out over the water and up into the sky, I follow them. She whispers in my ear, her mouth on my neck, and the tears come, the dancing lights pulling me over. Her laughter is with me and I take it, I hold it, and let it cushion me as I fall to embrace the rocks below.

By now I hope you are involved, that you care, and the entire story should wash over you. What did I promise you from the beginning—love, hope, surrender? In the first paragraph I mention that these great hands might punish him for his sins, and that his love has forgiven him. His conflict was in not wanting to surrender, to kill himself, and yet, he wants to be with his Isabella. So he follows her off the cliff, follows the lights, as he feels her mouth on his neck, her whispers in his ear as she laughs. He embraces the rocks, a gesture of love, wanting to be close to something, that word choice is on purpose. And in the end, they are together. Whether she was innocent or tainted, that’s up to you to decide.

CONCLUSION

I know this was a long column, so if you’re still with me, thank you. I hope that you got some insight not only into my thought process, the way I write, the structure and content, but also got some ideas about how to make your writing better, to be more aware of what you are creating as you are writing it, how to start it off right, to maintain tension, and to end it with power and authority. What do you think? Where did I screw up in this story? Did it work for you? Did I miss any opportunities? Could you see this expanding into a novel? What if he woke up the next day, still alive, how would that change everything? Keep writing, and evolving, and I hope you had at least one epiphany while reading this column. Onward and upward!

TO SEND A QUESTION TO RICHARD, drop him a line at Richard@litreactor.com. Who knows, it could be his next column.

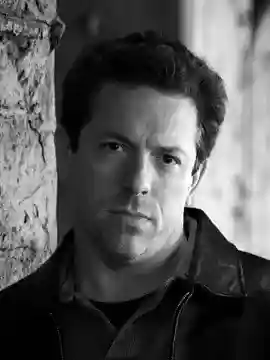

About the author

Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of seven books: three novels—Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), as well as Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); three short story collections—Staring into the Abyss (Kraken Press), Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press), and Tribulations (Cemetery Dance); and one novella in The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). With over 140 stories published, his credits include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice), Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker winner), PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous, Chiral Mad (numbers 2-4), and Shivers VI (with Stephen King and Peter Straub). He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year six times. He was also the editor of four anthologies: The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker, Shirley Jackson, and Thriller awards. In his spare time he is a columnist at Lit Reactor and Editor-in-Chief at Gamut Magazine. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.