Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.

—Rudine Sims Bishop, "Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors" from Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom. vol. 6, no. 3. Summer 1990

For writers and other creators of fictional worlds, 2017 and beyond needs to be about crafting characters and fictions that don't support or excuse or ignore colonialism, marginalization, and other forms of oppression. That means creating inclusive fiction that reflects of the diversity of the world we all live in. Representation is key to good writing. This is true whether you're a novelist, a playwright, or a screenwriter; whether you work in television, in game development, or new media. All narrative has the power to impact culture and individuals in a positive way or a negative one. It's up to creators to choose.

Writers often run into difficulties when attempting to represent people from identities very different from their own. It's not an easy skill to learn, and creators are often afraid of getting it wrong. That fear is a valid one, but representation is so important—too important to ignore. This is why I teach classes on Writing the Other alongside Nisi Shawl, co-author of the foundational book on the subject. We start our classes with this topic, relying heavily on the anthologies Invisible and Invisible 2, collections of personal essays on representation edited by Jim C. Hines.

Why Is Representation Important?

For readers and viewers, seeing themselves represented on the page or screen can open up to them what's possible. For some, it's a lifeline.

...at the time, I needed to see those multitudes of reactions. At the time, I needed an idea of what might happen when I came out... I needed to know that coming out – after years of silence – was an option. I needed to be told it wouldn’t kill my family or my friends and that there would be people who loved me at the end of that day.

—Joie Young, "Options" Invisible

This is particularly important for writers who create media for young people. If kids and teens feel excluded, alone, or like there is no one with their same or similar headspace, fiction can show them that this isn't true.

When I was younger, reading about shy and introverted characters helped me feel like I wasn’t the only shy, introverted person alive in the world, and like those traits were just personality differences, not flaws I had to fix. I have every reason to believe that, if I’d had the chance to read more books about non-binary characters as a teen or young adult, I could have understood and accepted my gender identity many years ago.

—Morgan Dambergs, "Non-binary and Not Represented" Invisible

Seeing oneself reflected in fiction, even if partially, is important for people from marginalized communities and identities. It's also important for people who align with the dominant paradigm as well. It allows them to see and understand that people who aren't like them exist outside of narrow stereotypes and also outside of the confines of their own narrow understanding.

One of the arguments against being more representative or inclusive in fiction is that authors and creators are including non-white, non-male, non-straight, non-able-bodied, etc. characters in settings where they don't belong. See anger over the casting of Angel Coulby in the role of Guinevere in BBC's Merlin, or pushback to the very idea that Marvel's Agent Carter needed to step up its diversity, or discussions of how Disney's Frozen could have been more inclusive, but wasn't. There is always someone ready to place restrictions or boundaries on creators due to genre, time period, or location, but they're often based not on what is actually possible, but what people think is possible based on faulty information, lack of representative examples, or just plain bigotry. Writers should reject these restrictions.

Because accepting these poorly supported boundaries results in what author Justina Ireland calls An Apartheid of the Imagination:

In all of my reading and book devouring, not once did I read a book that featured a black girl or woman. There were no black girls slipping into fantastical worlds and saving prophesied kings. There were no dark-skinned girls facing down their serial killer boyfriends or black women falling in love with their millionaire bosses…

Magic, love, and heart-stopping action just didn’t happen for black girls. We didn’t exist in those spaces, in those books. It was an apartheid of a different kind, a literary genocide for black women, and by extension, an apartheid of the imagination. By reading those books, I began to believe that those things also didn’t and couldn’t exist for me.

Reject the idea that you can't include a type of character in your fiction and instead, like author Anne Lyle, work on finding ways that you can.

Just don't fall into the trap of thinking that any representation should be welcomed by groups who lack it.

Bad Representation: Like Water In The Desert

When readers and scholars from multiple Native American Nations spoke out about the many problems with J. K. Rowling's Magic in North America stories, one of the comebacks I saw often from angry fans was: You should be glad she included you at all!

This is a common argument, and one that should be ignored.

It is true that if you never or rarely see yourself in fiction or other media, any representation that matches you, even a little, can feel welcome at first. It's like coming across water in the desert after a day without it. Doesn't matter how foul or gross looking the water is, you're gonna drink it if you're dying of thirst.

In retrospect it’s incredibly offensive, and even at the time it wasn’t very funny. But at the time I thought to myself, ah! This is what I am!

—Susan Jane Bigelow, "Clicking" Invisible

The problem with accepting bad representation as the norm or as desirable going forward is that it leads to more bad representation, more stereotypes, more offensive caricatures. And that has a negative psychological effect on the people represented.

Scholar and activist Debbie Reese introduced me to this study: Of Warrior Chiefs and Indian Princesses: The Psychological Consequences of American Indian Mascots. You can read it in full at the link, but here's the takeaway: The study measured Native American students' self-esteem, community worth, and their sense of achievement-related possibilities before and then after being exposed to common American Indian stereotypical images such as Pocahontas and sports mascots like Chief Wahoo and Chief Illinwek. Before, their self esteem, etc. was high. The study found that after exposure to these images and stereotypes, the students felt less good about themselves, their communities, and their future. On the other side, the self-esteem, etc. of white, Western children exposed to the same images went up.

Bad representation has a direct negative effect on the groups being represented.

It also affects how gatekeepers judge a piece of media. If an editor, producer, or lead developer is convinced that characters from an identity group must act or be a certain way in order to be realistic, and those ways of being are reinforced by stereotypical representation, then they force those ideas onto writers. All Native Americans must struggle with alcoholism! All young Black men must come from a broken home and be in or attracted to gangs! All women must have a desire to be mothers and must be devastated to discover that they can't bear children! All trans people must be unhappy and self-loathing unless and until they can medically transition and pass as cisgender!

Writers can combat this by working toward including nuanced and realistic representation in their own work whenever possible and resisting the pressure to change it. Arm yourself with knowledge on the subject, find experts to back you up, get your agent or your team to back you up. It's not going to be easy. But it's crucial for you to hold firm about not allowing someone else, no matter how powerful they seem, to introduce harmful stereotypes into your work because they lack understanding.

Representation Needs Change Over Time

There's an aspect of the Water In The Desert discussion of representation that I address with our students when they ask: But What If I Get It Wrong?

Here's an uncomfortable truth: You're Going To Get It Wrong, Sometimes. Even if you try your best. No one is perfect, this work is not the work of a month or a year or, for some, a decade. It's ongoing, and sometimes the needs of the people you're representing are going to change around you.

A famous case to study: Neil Gaiman's Sandman: A Game Of You.

If you're not familiar with this graphic novel, I suggest you read this plot summary on Wikipedia.

The collected comics were first published in 1991 and 1992, and at that time there was a dearth of transgender people in media anywhere. A Game of You features one as a main character: Wanda. Many trans people, especially ones who first read the comic in the 90s, love Wanda. Many trans people think the character and the story are steeped in transmisogyny and transphobia.

There are many examinations and criticisms of the story on the Internet. The one I point my students to is by author Imogen Binnie. The essay is long, very detailed, and contains too many good points to quote faithfully here. Binnie starts by pointing out that, up to this point, there have already been eight trans women mentioned or shown in the Sandman series, all of whom were dead. Wanda is the first full-fledged trans character with lines. Despite this being groundbreaking by admission, Binnie still finds Wanda "a boring caricature of a trans woman" whose freakishness is often highlighted in opposition to the "normative cis[gender] femininity" of most of the other major characters.

In the course of the story, Wanda is denied access to the quest her friends embark on because the Moon (which represents anti-trans Dianic Paganism) won't allow her to walk on the Moon's Road because "she's a man." While her cis women friends are off on their adventure, a hurricane destroys their apartment building and Wanda dies. (This is a very, very brief summary that doesn't do any of the story justice, so please do read the summary and Binnie's essay in full.)

After this, Wanda's best friend Barbara tells us:

"I dream of Wanda. Only she’s perfect… And when I say perfect, I mean perfect. Drop-dead gorgeous. There’s nothing camp about her, nothing artificial. And she looks happy."

Binnie's commentary dissects the takeaway as:

See, Wanda is happy because now that she is dead, she looks cis. Again: not only does this reinforce cissupremecist beauty standards, but what does this say to a trans person who’s reading this: you will look pretty when you’re dead, but since you’re alive right now, … that must suck for you?

It breaks my heart to re-read this because this was my favorite scene in the whole series when I was younger. I felt SO FUCKED UP when I read it. It was SO BEAUTIFUL, she finally got to be pretty, she finally didn’t have to be trans any more, she got to wear a pretty pink princess dress (like Barbie!) and wear subtle makeup and her big red hair didn’t look absurd, it looked natural!

Imogen is far from the only person to point out these aspects of the story and characterization as a problem. There are also very staunch defenders of this story and Wanda in specific. The two I'm going to quote are close friends of Neil Gaiman. This might make you think their views are too biased to be useful in this context—in this case, not so.

When creating the character of Wanda, Gaiman did all the things Nisi and I and dozens of other people who encourage authors to write the Other to do: Talk to people from the group you're trying to represent. Understand their struggles and concerns and what they want to see in characters that represent some part of them. Show these people your work and get their honest feedback.

Cheryl Morgan and Roz Kaveney, trans authors, editors, and activists, are among the loudest voices who consistently defend Wanda and Gaiman's portrayal of her against criticism, both unwarranted and thoughtful. These quotes are from a discussion on the subject from Facebook (no link for privacy, included by permission):

Roz Kaveney:

Neil's portrait of Wanda in A GAME OF YOU drew extensively on the experiences of various trans women - it's of its time, the early 90s and is open to criticism some twenty years later. It was ground-breaking - Wanda was one of the first major trans characters in popular culture - and it was not ill-informed. ...The claim that Neil is in any way transphobic is an insult to all the close trans friends he had long before he became a star.

In response to the essay linked above:

I am not discounting Imogen's reading, just saying that it doesn't invalidate other readings by other trans women.

Cheryl Morgan added:

I can totally see where Imogen is coming from. The story is not an easy thing to read, especially if you are a trans woman. Where I might disagree is in labeling the story transphobic. It is very much a story about transphobia. It has TERFS, it has religious fundamentalists, it has horrible parents. Inevitably it is very triggery. … By the way, the reason that Roz and I are so protective of Neil is that he has been a loyal and supportive friend to both of us for many decades, when many other people we might have expected to rely on have been far less accepting of our trans status.

From everything I've read and heard on this subject, it seems clear to me that Gaiman tried to create a character that honored and represented his trans friends. And yet, for some trans people, the character still comes off as harmful.

Gaiman has been asked about Wanda many times. He answered one of his critics on Tumblr by saying:

If I were writing it today, rather than in 1989, when there weren’t any Trans characters in comics, it would be a different story, I have no doubt. But that was the story I wrote in 1989.

What comes off as good, or good enough, will sometimes depend on where the culture is at the moment. The first representation can be exhilarating, as Binnie points out. That doesn't mean it will always be good enough, or even celebrated forever. And it's not entirely in your control as the creator. You may go years, decades with people from the identity group you're representing who think the portrayal is on point, even a needed lifeline, and then later find other people from that group saying your character is harmful and doing the opposite of what you wanted. Sometimes that will be because the culture has changed for the better.

How do you avoid this?

What To Avoid, What To Strive For

I'll say again: You're Going To Get It Wrong, Sometimes. Be prepared for that. However, there are things to watch out for that could help future-proof your characters.

The Perpetual Victim

Avoid only including marginalized characters who are victims or only exist to be victimized.

Even if they are done well (such as by Guy Davis in his old Baker Street comics), it seems like victimisation is inevitable. Murder, assault, being outcast, etc. are all common situations applied to trans* characters... and even if they survive the story it’s often not without some sort of violent conflict.

—Katie, "Gender in Genre" Invisible

It's easy for writers to fall into this because many marginalized people in the real world do suffer from oppression. You shouldn't ignore that, but you also shouldn't make that the only way you include them as characters in your work. People are complex, live complex lives, and experience awesomeness as well as pain. If the only narratives you can imagine for marginalized characters focus on the pain, then you're not going deep enough.

Characters in Isolation

When creating characters from under-represented groups, remember that they shouldn't be the only person from that identity in the work. The majority of characters don't spring fully-formed from the head of Zeus. That person had to come from somewhere. They have People. A family, a community, a group they've forged themselves. They also weren't the only person to arise from that culture, group, or family. If your inclination is to make any marginalized character isolated, interrogate that inclination. Ask why.

This is not only more realistic, it will also give you more wiggle room when it comes to reader reactions to these characters. When discussing this essay with Cheryl Morgan, she pointed out that: "...if you put a representative of a minority group in a story, then readers who come from that minority group will probably identify strongly with that character. And if bad things happen to that character, even if that's entirely justified within the story, those readers will feel that as an attack on them. Neither you, nor any other reader who is not part of that group, will read the story in the same way, because it isn't so personal for you."

You don't have to make every character from a particular identity a prominent one to combat this problem. However, if you have a limited cast to work with, remember that, like people, characters aren't only one thing. A trans person is not only their gender or gender presentation, they have a race or ethnicity, may be abled or disabled, hold religious beliefs, and can come from a variety of class backgrounds, like any other type of person. Including multiple transgender characters in one work doesn't mean only including people from the exact same background and experience.

Villains and Saints

Another trope to avoid is only including marginalized characters as villains. This is explored in depth in "Evil Albino Trope is Evil" by Nalini Haynes:

The evil albino trope is lazy writing, creating a sense of ‘other’ by victimising a small minority group. The evil albino trope alienates albinos… Reinforcing perceptions of incompetence and evil-ness in this people group is discrimination and victimisation.

Not that all minority/marginalized characters must be the ultimate paragons of good—that's also a problem. As we tell our students: reject the binary. The answer is rarely either/or. It's more complex.

If you're going to make the marginalized character the antagonist or even evil, take care to ensure they are not the only person of that identity prominent in your work. Again, avoid characters in isolation.

I See (Only) Dead People

Avoid killing all the people who represent marginalized or minority identities in your work of fiction. That doesn't mean some can't die, but if all the characters who aren't the white, cisgender, able-bodied hero types die, that represents a problem. Wanda was the tenth trans person to die by the end of Sandman #5; none of the trans people mentioned or shown up to that point got to live. Wanda's death may have been narratively apt or even necessary, that doesn't mean it should or will only be viewed on its own.

Marginalized characters often die while characters that hew closer to the dominant paradigm (white, cisgender, able-bodied, heterosexual, or male) go on. Consider very carefully when you make this choice as a creator.

That's a bunch about what you shouldn't do, here's some of what you should do.

Educate Yourself

Whenever possible, learn about the stereotypes and tropes already present in media about the groups you're trying to represent. TVTropes is an excellent place to start if you are at the very beginning of your search, just don't let that be where you stop. Find articles, essays, blog posts, social media threads where media critics and activists dissect books, TV shows, and movies with characters from the groups you're learning about. Look at the mistakes others have made, understand why people in the group see them as mistakes, then don't make the same ones yourself.

Create Complex Characters

That may sound simple and obvious. It is. It's just not always easy when the characters are very different from you. It requires empathy, understanding, willingness to do hard work, to examine yourself as deeply as you examine others, and sometimes a good deal of research. It's not impossible.

If you want some guidance on how to start, we have a whole section of Resources on the Writing The Other website, many of them free. You'll find links to books, online essays, and videos that go into the topic. You'll also find our classes, which range from courses that offer a foundation in writing inclusive fiction to master classes on writing characters from specific identity groups. We also have a class coming up here at LitReactor on Description, Dialect, and Dialogue. If you take one of our classes, you also get the opportunity to join our community of alumni made up of talented, generous writers dedicated to gaining greater skills in this area and helping others do so as well.

There is all kinds of help out there beyond our website for making sure that the fiction you create can serve as a mirror as well as a sliding glass door. Find it, utilize it, and always strive to do better.

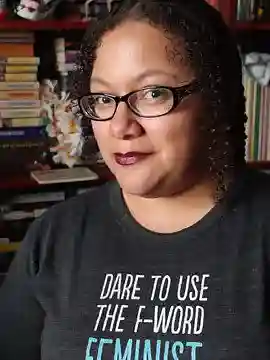

About the author

K. Tempest Bradford is a speculative fiction writer, media critic, reviewer, and podcaster. Tempest’s fiction has appeared in award-winning magazines (Strange Horizons and Electric Velocipede) and best-selling anthologies (Diverse Energies, Federations, In the Shadow of the Towers); her essays and criticism have appeared on io9, NPR, Tor.com, Chicks Dig Time Lords, Chicks Unravel Time, and The Usual Path to Publication. She volunteers for a number of non-profit organizations, served as a juror for the 2008 James Tiptree Jr. Award, organized fundraising auctions and salons for the Interstitial Arts Foundation, and raised funds for Clarion West, her writing workshop alma mater. Currently, she serves on the board of the Carl Brandon Society, an organization dedicated to increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the production of and audience for speculative fiction.