Post-Mortem: As much a book review as an autopsy is a eulogy. A breakdown of the mechanics of a book and the reasons why it should be read by the writers among us.

Whether it’s a book or a body, what lies in front of you can be taken at face value. You can say “Yup, that’s a dead body” and move on. You can read a book, and say “Yup, that was a good book” and move on. And that is fine, for some - on a cursory level, that may be all you want. But when you really open a book up, so to speak, you see all the little clues that bring additional layers of understanding to what lies before you, just like with a body.

So this isn’t really going to be a book review any more than an autopsy is a eulogy. In this column, we are going to dissect a book with some specific criteria in mind:

• Why this book is worth the read

• Why this book is worth the read to a writer

• What works and doesn’t work in the book

• What should be considered or avoided in this book as it may pertain to your own writing

The book that’s on the slab today is one of my all-time favorites, and it is a book that never fails to spark debate among its readers: Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves.

HoL initially gained popularity for its unique use of formatting, typesetting, codes, and the broad interpretations people have taken away from their own reading(s). It has been described as a book of horror, a love story, a satire, and an unholy mess. There is some truth to all of these. But before we get into opinion, let’s take a look at some of the mechanics of HoL.

Nesting doll of a story

The book is entitled House of Leaves (what is a book if not a literal house of leaves/pages?), a story written by Johnny Truant, taken from a manuscript he found that belonged to the now deceased Zampanò, who wrote it as a treatment/diatribe/thesis on a film shot by Will Navidson about a rather unusual house on Ash Tree Lane. When you read this you think: mess. But when you look at what Cunningham did with The Hours (three narratives) or what Charlie Kaufman did with Adaptation (three narratives), you begin to see the benefits of this style of writing. 1) The action never tires or stretches on too long with one character. 2) There is a relationship between them that you remain tethered to in the back of your mind as you read any one passage. Which brings me to:

The rule of threes

HoL has three stories within it, each with their own protag, and each story contains three individuals/relationships. The benefit here is pretty obvious: while you get good conflict with two characters, you get even greater conflict and the possibility of additional outcomes with three. But beware, three is the magic number. If you go on some Pynchon-esque character creation spree, you run the risk of losing the focus of the story and the reader.

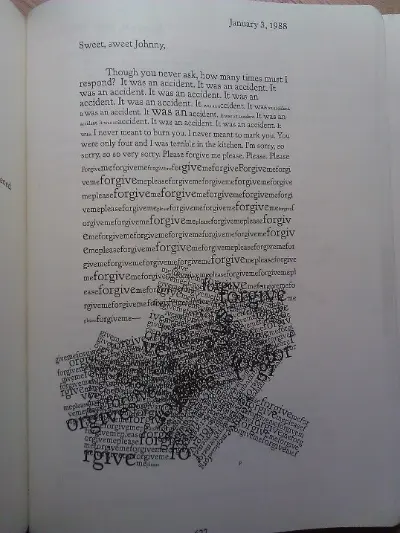

!['House of Leaves']() Fontalicious

Fontalicious

Why font matters: By now it’s pretty much common knowledge that Johnny’s narrative is written in Courier font, the Editors are in Bookman, and Zampanò is in Times. So in a small and subtle way, the font choice informs the reader of the roles of the various voices. Plus, the font shift does help in keeping the narrative overlap in check. And personally, when you’re aping a scholarly work, the more the fonts shift, the more credible it looks.

Formatting

MZD flew himself up to NYC to personally oversee the formatting of HoL, as it was uncertain whether or not his strict formatting would be adhered to, or if the publisher could even pull it off, as this kind of formatting was unheard of in the industry. Can it get a bit overwhelming at times? Sure. But who doesn’t secretly enjoy reading what was supposed to be redacted? It’s the font equivalent of looking through the mini blinds. And the use of whitespace can inform the reader in ways that the narrative cannot, and in ways that interact with the narrative without overtly informing the reader from within the narrative. So, there’s that.

Footnotes

The footnotes, for the most part, serve to inform in small ways, as footnotes do. The notable exception being the shift in narrative from Zampanò's record to Johnny’s. Instead of using the boring page break or dissective mini-chapters, MZD allows for complete and utter shifts in POV and narrative by way of footnote – a clever trick that keeps the reader engaged; we typically take a mental pause at a page break, a larger, more reflective one at a chapter heading. By keeping the multiple threads going at speed, the reading sensation is a unique one, and the action remains bound tight, the plotlines running together as Spanbauer’s horses.

Codes

Do they add overall meaning to the narrative? Not to a great degree. But do they add to the reader’s experience? I’d argue yes. Without giving away too much, the section entitled The Whalestoe Letters has one very informative code. But is the many little touches- some merely playful, like the inclusion of the author’s name, some quizzical, like the check mark on page 97- that serve as bait for another reading of the book.

Poking fun at academia

If we take what we know about MZD and apply it to our reading of HoL, we understand his disdain for academia. This is more a personal agenda from MZD, but it also translates to some nice hidden meanings, and if you enter the book forearmed with that information, you get some interesting riffs on Clara English (who spoke of her rape), Thumper, and all the gendered genres Johnny Truant has hooked up with throughout the narrative.

Then there is the entire library of fake publications (so numerous as to have populated a Wikipedia page by themselves).

And of course, the Appendix that makes up about a third of the book’s final page count (also populated with fictitious entries). All under the guise of a scholarly, critical work.

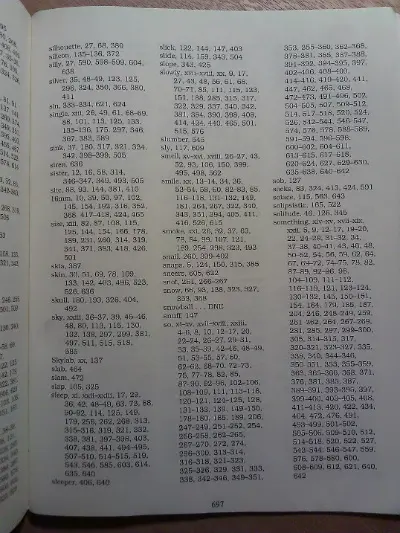

!['House of Leaves']() Index

Index

The air of nonfiction to a novel is always a good thing. The impact goes way up. Why do you think so many people have been busted for taking exaggerated license with their memoirs? Why do you think the publishing industry has leaned to this with self-spawning genres such as “narrative non-fiction?” But when looked at from the opposite end, a novel that injects relative fact into the mix – as most novels are prone to do (again see The Hours)- this is a Good Thing.

House in blue

In an interview MZD stated that this was to evoke the idea of "house" as an effect – the color is the exact shade of chroma-key blue that was used in “blue screens”. There are numerous debates as to the meaning of this, but I think the imagery is pretty self-explanatory.

Why this books aggravates (instrument versus cd)

This is non-linear literature. Well, not as nonlinear as his follow-up Only Revolutions. HoL still remains somewhat attached to a conventional storyline/plot arc. But with the nested nature of the three narratives, and the opening flashback “introduction” letter actually being the end (or is it?), this book can be confusing, especially if (and you should) one attempts to take in all the footnotes and quotes and little bits of literary flotsam that are scattered across the pages of this book. Too, some find the formatting a bit overt. Some people just don’t like being forced to turn a book sideways. Some people get uncomfortable when the text gets too condensed, or is written in red with a strikeout running through entire paragraphs, or when the text takes the shape of a minotaur.

In an interview, MZD defended his mechanics by stating that his books “aren’t cd players, they’re instruments” which is a superb metaphor for his writing. Today, when you want to hear a song, you just press “play”. But a book like HoL requires a bit more patience of the reader, if the reader is to extract the real reward of reading. We all know about the reader/writer contract, but with this book, you have a multi-page contract, in triplicate, that you need to initial several times. But the payoffs can go so much further than in a typical book, a typical story.

The story itself

So far we’ve focused on the mechanical nature of the book, but what of the story, stripped of formatting and fonts and layout?

Well, at the core of it all you have a very interesting premise, one the requires a degree of suspension of reality from the reader. Specifically, the fact that something as static as a house is now shifting and changing. Not just with a ¼” here or there, but as we learn, with a five and a half minute hallway, and even larger expanses that cannot be bridged by echo or light. We also learn that these changes and shifts are dependent upon the people who enter the house – as if the rooms and halls are tailored to the traveler. Of course, within the dynamic of this struggle, i.e. Will’s desire to explore and quantify/rectify this strangeness in his home, is a love story. A love story between Will and Karen, and a loss story between Will and Delial.

Now wrap that up in the solitary sadness of Zampanò, the real architect of the entire mess, and you have the age old story of the tortured writer, blind no less in the tradition of Borges. Wrap that further still in the story of Johnny Truant, who wrestles with love, his past, and the compass-free existence he bounces around in.

Three stories of loss and love, bound by a common, albeit very unusual house on Ash Tree Lane. These rather conventional conventions of fiction are then further cocooned in hours of extra reading. But the extra reading, the fictitious entries serve the narrative: they enlighten the murkier areas of the relationships between Will and Karen, Johnny and Pelafina, Zampanò and history, even MZD and his father.

They say there is nothing new under the sun. They even said this in 2000 when HoL debuted, a novel on its 35th printing as of the time of this writing. And while the cores of this book are rather time tested, the best way HoL informs the writer, in my opinion, is that you can always take the existing and twist it. Reshape it. Much as modern art has done by taking seemingly ordinary objects and assigning new meaning to them. HoL takes tried and true themes and assigns them new meaning, not just with mere craft and superb writing, but with new takes on the mechanics of reading, the use of font, and the weaving together of multiple threads for the greater good of the whole.

P.S.

A good place to start if you want to tear into the mind behind this book, the impetus that impelled said mind, and all things HoL, would be to start with an interview, which conveniently, I happened to conduct awhile back at ChuckPalahniuk.net.

And if you think you can get lost in the book, try spending some months among the official forum.

Get House of Leaves at Bookshop or Amazon

Get Only Revolutions at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Just another ink-stained wretch who writes on the subject of wine, with the occasional literary luminary interview thrown in.