My last column dealt with George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, and why I thought it was important. One of the reasons that series hit so close to the mark for me was that after growing up with a voracious appetite for epic fantasy in the vein of Lord of the Rings, I eventually grew tired of it. I didn’t feel like large, sprawling fantasies in medieval European settings were offering me anything new, anything I hadn’t seen in slightly different forms elsewhere. The last epic fantasy I remember being impressed by before A Song of Ice and Fire was Tad Williams’s Memory, Sorrow and Thorn series, which eventually helped to inspire Martin’s own take on the genre.

That epic fantasy fatigue is why I understand when people say they aren’t into fantasy. Too often those derivative epic fantasies come to represent the whole genre, and that makes it seem stale. I’m not saying that writers don’t make their versions unique, but the tale of the farmboy who becomes king amidst an epic battle between Good and Evil has been done to death. Which is why I like to suggest that people look to fantasy settings outside those traditional epic-fantasy worlds.

For the purposes of this discussion I’m looking primarily at secondary worlds, worlds created wholly by the author and therefore not our Earth. Fantasy is rife with secondary worlds, and some of the most famous are worlds like Middle Earth, Narnia, Oz, Earthsea. But I’d like to shine the spotlight on some non-medieval settings (or in the last case, a non-traditional medieval setting). In all of the following examples, the setting is as much a part of the book as the characters and plot. In a sense, all of these locations are characters.

Ambergris

Ambergris is the setting of three of Jeff VanderMeer’s books -- City of Saints and Madmen, Shriek: An Afterword, and Finch. Like most of the settings on this list, Ambergris is a city, though it is part of a larger fictional world. Unlike the medieval worlds mentioned above, Ambergris at the time of the first stories seems to come from a technological era more similar to say the 17th or maybe early 18th century. For me Ambergris always had a kind of European feel, but a post-colonial Europe. Some of the images evoke a Paris or Italy, but you can sense the influence of the equivalent of the Middle-East or Asia hovering on the edge.

Many of VanderMeer’s stories veer into horror and I’d contend that part of that is because the city, with all its dark and weird happenings, can often remind us of the world in which we live.

Ambergris is as filled with the mysterious, the odd, and the grotesque as a carnival. Mushrooms and other fungi feature heavily in the Ambergris stories, and that sense of richness, that sense of bloom and decay seems to color the whole city. In fact, there’s almost an odor of the sickly sweet about the whole place when you’re reading about it. And, like other kinds of mushrooms, it can sometimes verge on the dreamlike or surreal.

The city might be savage, stray dogs might share the streets with grimy urchins whose blank eyes reflected the knowledge that they might soon be covered over, blinded forever, by the same two pennies just begged from some gentleman, and no one in the fuming, fulminous boulevards of trade might know who actually ran Ambergris—or, if anyone ran it at all, but, like a renegade clock, it ran on and wound itself heedless, empowered by the insane weight of its own inertia, the weight of its own citizenry. - "Dradin, In Love," City of Saints and Madmen

The most fantastic element of the city, aside from the general sense of weirdness that seems to pervade it, has to be the presence of the mysterious Gray Caps, a mushroom-like people who were the original inhabitants of Ambergris. Their presence and their agenda are explored throughout the stories and they embody much of the mystery and darkness of the fiction.

What helps Ambergris to truly live is that unlike some other fictional cities, it actually changes over time. I once heard VanderMeer remark that real cities change tremendously over time and that fictional cities should, too. The span between the first Ambergris story and the last is 200 years and change is evident in that time frame, not just in architecture, but in technology. The technology level of the early stories seems almost Victorian whereas in Shriek: An Afterword there are cars and firearms. By the time of Finch, Ambergris technology has moved into the equivalent of our mid-20th century. Like any other character, the city grows and changes.

Ultimately, though, what makes Ambergris work, even more than the strange fungal weapons of Shriek or the Festival of the Freshwater Squid, is the fact that it reflects real cities, that it is recognizable to us, even if it’s fantasy. Many of VanderMeer’s stories veer into horror and I’d contend that part of that is because the city, with all its dark and weird happenings, can often remind us of the world in which we live.

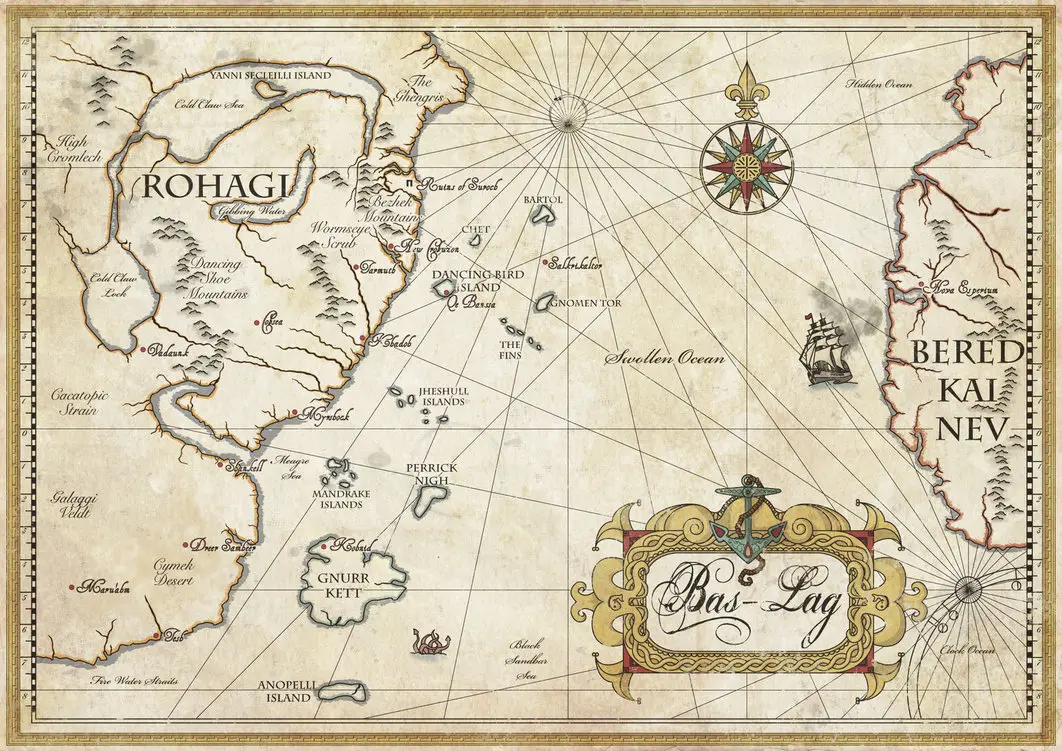

Bas-Lag

China Mieville’s Bas-Lag appears in three of his novels - Perdido Street Station, The Scar, and Iron Council. You know you’re in for an original world when you open the pages of Perdido Street Station, which takes place in the city-state of New Crobuzon. Instead of the stereotypical elves and dwarves, New Crobuzon is populated by Cactacae (humanoid cacti), Garuda (bird people), Vodyanoi (a froglike aquatic people), and the Khepri (humanoids with scarab beetles for heads) in addition to common humans. There is magic, of course, these being fantasy books, but there is also science. Using a kind of steampunk level of technology, Mieville includes primitive robots as well as Remade, people who have been altered, some merged with machines. And then, of course, there are the Weavers, spider-like creatures who can exist between many dimensions and sometimes interfere in the course of events. And these are just some of the races and creatures that Mieville introduces over the course of the three books, not to mention technology and magic. Like Ambergris, the setting evolves over time.

Photo credit: ~JenJenRobot, from Deviantart

Also like Ambergris, Bas-Lag, and specifically New Crobuzon, seems to overflow with the dark and the weird. Mieville’s creation is full of the grotesque and the beautiful, often side by side, sometimes in the same individual. Female Khepri, for example, have the bodies of human females, though their heads, as mentioned, are scarab beetles. They also can create wondrous works of art by excreting from their scarab parts.

“The city reeked. But today was market day down in Aspic Hole, and the pungent slick of dung-smell and rot that rolled over New Crobuzon was, in these streets, for these hours, improved with paprika and fresh tomato, hot oil and fish and cinnamon, cured meat, banana and onion.” - Perdido Street Station

New Crobuzon is gritty and urban with effluvium from smoke stacks spat out into the air, and massive, looming structures like the titular Perdido Street Station. The city is run by a corrupt and sometimes brutal government, and yet criminals, artists, spies and junkies eke out a living in its cracks and crevices. When some writers play it safe by sticking to the familiar, Mieville goes all out in painting and populating Bas-Lag, and while many of his creations are inspired by real world mythology, he makes all of these elements his own.

The City and the City

I place another of Mieville’s creations on this list precisely because of its difference in style and scope from Bas-Lag. Besźel and Ul Qoma are fictional cities existing ostensibly in our own world in the novel, The City and the City. Even for fantasy, they are fascinating creations. Both cities occupy the same space, but overlap in some areas. Denizens from one can see into the other and vice versa except that laws exist to prevent this. As a result, citizens must “unsee” the other city. If this careful arrangement is violated, a breach occurs and an organization, suitably shady, called Breach must deal with it. Upon this compelling framework, Mieville constructs a murder mystery that ends up involving both cities and Inspector Tyador Borlu, originally of Besźel, must cross into Ul Qoma to investigate.

With a hard start, I realized that she was not on GunterStrász at all, and that I should not have seen her. Immediately and flustered I looked away, and she did the same, with the same speed... When after some seconds I looked back up, unnoticing the old woman stepping heavily away, I looked carefully instead of at her in her foreign street at the facades of the nearby and local GunterStrász.

Unlike Bas-Lag which is a cornucopia of ideas and elements, Besźel and Ul Qoma are more subtle creations, more restrained but no less powerful. Though they exist on the fringes of Europe in the novel, they are original, each with their own sense of culture, their own languages, their own realities. Besźel, for example, is a declining city with its best years behind it while Ul Qoma seems to be on the way up, scoring the best trade agreements. In some ways, creating believable fictional cities in our own world is harder than a secondary world and yet Mieville pulls it off, imbuing each city with authenticity.

In some ways, creating believable fictional cities in our own world is harder than a secondary world and yet Mieville pulls it off, imbuing each city with authenticity.

Yet what really makes these cities truly powerful is that they reflect our own world back at us. Like the denizens of Besźel and Ul Qoma, we often learn to unsee things in the world around us, and framing these things in fiction can often highlight them. So the kind of blindness we have as part of one society looking out at another, the unseeing that we do in our daily lives, becomes clear as we read about it in Mieville’s fictional cities.

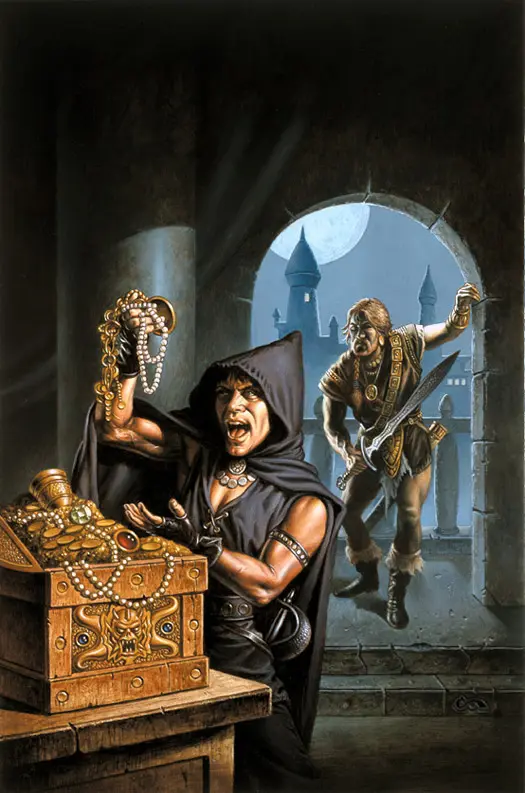

Lankhmar

I would be remiss in listing non-tradtional settings if I didn’t mention Lankhmar, one of my favorite fictional settings of all time. While technically medieval in era and technology, Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar, the setting for the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories, was one of the first such fantasy series to shift its attention from the country to the city and to alter the scope of the stories from the fight between Good and Evil to the fight of two rogues to get by. Part of the allure of such sword and sorcery tales was moving the focus to the characters and making the ultimate struggle a more personal one.

Unlike the love of the pastoral that Tolkien showed in Lord of the Rings or that Lewis had in the Narnia books, Leiber filled Lankhmar with smoky bars and seedy back alleys. Like some of the other cities mentioned previously, it’s filled with characters who would be seen as villainous in any heroic fantasy -- thieves, crime lords, beggars, corrupt priests, shady mages, and so on. Even the heroes of Leiber’s Lankhmar tales, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, are often little more than thieves who hire themselves out for coin.

Like most of the other cities on the list, though, Lankhmar is overflowing with strange delights and mysterious dangers. Though a city with taverns and a Thieves Guild may now seem commonplace to anyone who has ever played D&D, the elements of Leiber’s stories still drip with originality whether it be the undercity populated with sentient rats or Fafhrd’s turn as a servant of the god Issek of the Jug. And while Lankhmar has a largely European feel to it, with its temples and bazaars it shows influences of both Middle-Eastern and Asian cultures as well.

In fact, while Lankhmar is the setting of many of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser’s stories, it’s just part of Nehwon, the larger world, which, too, contains strange, wondrous delights like the Cold Waste, Fafhrd’s birthplace, where snakes are furred and hot-blooded. Or the hut of the wizard, Sheelba of the Eyeless Face, which crawls around on posts, not unlike the hut of Baba Yaga. Even better, it doesn’t take itself seriously and indeed many of the Nehwon stories have humorous elements.

"Sundered from us by gulfs of time and stranger dimensions dreams the ancient world of Nehwon with its towers and skulls and jewels, its swords and sorceries. Nehwon's known realms crowd about the Inner Sea: northward the green-forested fierce Land of the Eight Cities, eastward the steppe-dwelling Mingol horsemen and the desert where caravans creep from the rich Eastern Lands and the River Tilth. But southward, linked to the desert only by the Sinking Land and further warded by the Great Dike and the Mountains of Hunger, are the rich grain fields and walled cities of Lankhmar, eldest and chiefest of Nehwon's lands. Dominating the Land of Lankhmar and crouching at the silty mouth of the River Hlal in a secure corner between the grain fields, the Great Salt Marsh, and the Inner Sea is the massive-walled and mazy-alleyed metropolis of Lankhmar, thick with thieves and shaven priests, lean-framed magicians and fat-bellied merchants - Lankhmar the Imperishable, the City of the Black Toga." —From "Induction" by Fritz Lieber

Dhamsawaat (from Throne of the Crescent Moon)

Of course there’s nothing wrong with epic fantasy worlds with swords and magic. Some writers are tackling non-traditional settings in their epic fantasies. Saladin Ahmed has created a pseudo-Arabian medieval world for his debut novel, Throne of the Crescent Moon, which mostly takes place in the fictional city of Dhamsawaat. Throne is influenced highly by sword and sorcery such as the aforementioned Lankhmar, but has a very distinct middle-eastern feel.

Instead of the usual knights or wizards or thieves, the heroes of Ahmed’s book are a veteran ghul hunter named Doctor Adoulla Makhslood and his dervish sidekick, Raseed bas Raseed. Later they hook up with Zamia, a young woman from a desert tribe who can turn into a lion. Together they fight ghuls, which are a bit like zombies, but not quite, raised by evil sorcerers to do their bidding. Ahmed's heroes are products of the world he's created, fresh and exciting but with a touch of the familiar to pull us in.

His friend was right about one thing: Adoulla was, praise God, alive and back home—back in the Jewel of Abassen, the city with the best tea in the world. Alone again at the long stone table, he sat and sipped and watched early morning Dhamsawaat come to life and roll by. A thick necked cobbler walked past, two long poles strung with shoes over his shoulder. A woman from Rughal-ba strode by, a bouquet in her hands, and the long trail of her veil flapping behind. A lanky young man with a large book in his arms and patches in his kaftan moved idly eastward.

Ahmed brings Dhamsawaat to life, detailing its sounds and scents, even going so far as to describe the foods that Adoulla eats in such a way that my mouth waters every time I read the passages. Dhamsawaat may seem like the Baghdad of the Arabian Nights, but Ahmed makes the city his own and populates it with a cast of characters that includes the Falcon Prince, a revolutionary, and Miri, Adoulla’s beloved who runs a brothel. I had the pleasure of reading this while in manuscript form and I was excited to see something that felt so fresh and different in the field of epic fantasy.

Further books in the series will focus on djinn and the version, in this world, of the Crusades, only from the Arabian perspective. I'm looking forward to seeing where this series goes and looking forward to more Arabian-influenced elements.

What are your favorite non-traditional fantasy settings? What attracts you as exciting and fresh? Or, if you are an epic fantasy fan, feel free to point out in the comments examples that avoid the well-worn ground mentioned above. I'd love to hear from you.

About the author

Rajan Khanna is a fiction writer, blogger, reviewer and narrator. His first novel, Falling Sky, a post-apocalyptic adventure with airships, is due to be released in October 2014. His short fiction has appeared in Lightspeed Magazine, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and several anthologies. His articles and reviews have appeared at Tor.com and LitReactor.com and his podcast narrations can be heard at Podcastle, Escape Pod, PseudoPod, Beneath Ceaseless Skies and Lightspeed Magazine. Rajan lives in New York where he's a member of the Altered Fluid writing group. His personal website is www.rajankhanna.com and he tweets, @rajanyk.