Now you can say it doesn't matter what an author is like as a person, it's all about the prose they create. You can say that and I will disagree. When I read Hemingway, I carry in my mental sidebar an indelible image of the man behind the prose: tweedy, moustachioed bourbon drinker; the man who liked to fish and hunt and whose idea of relaxation was to visit a bullring and watch a couple of toros bleed to death. I like authors to fit the prose they produce. Would I want to hear that Cormac McCarthy – producer of tightly worded, brutalistic fables – is actually a party pig with a penchant for soft rock and brightly colored cocktails? (He isn’t but you get my point.) No, I wouldn’t, any more than I would wish to discover that Jodi Piccoult is actually a rocket scientist with a PhD in astrophysics.

But sadly, over the years, my cherished beliefs about authors have been blown aside by the cold winds of reality and also occasionally by Wikipedia. Here are five writers for whom the truth gave me a long moment of disappointment:

![]() Jane Austen: Slush Pile Reject

Jane Austen: Slush Pile Reject

Let me start by admitting that I'm not a huge Austen fan. Apart from a spate of enthusiasm in my teens, I've always seen her work as tarted up bodice ripper material. Elegant, eloquent, but cast in the same wish fulfillment mode as thousands of lesser imitators. Austen's heroines might be a little more feisty than the average romantic protagonist, but however much they protest, they fall for the bloke in the end.

Still, what does elevate Austen above the crowd is her wit and obvious intelligence. She was a meticulous observer of the absurdities of her day and in that respect, she's unsurpassed.

My Cherished Belief

Because Austen's smarts crackle through her writing, I honestly believed that her rise to publication glory was as smooth and inexorable as her prose. I imagined her putting pen to paper one morning and delivering the complete draft of Sense and Sensibility to an enraptured publisher, error and revision free, about two weeks later. Not for her the years spent crying over mangled sentences, wonky plots, and wooden characters that is the lot of most other novices. No. Jane would have taken to writing like Pamela Anderson to home movies: in a seamless unity of talent and passion.

The Awful Truth

Austen’s first book - Northanger Abbey – failed spectacularly to make any mark on the reading public. In fact, it was so crap it didn't even make it into print. Intended as a pisstake of the gothic melodramas which were wildly popular at the time, Austen's first work failed to hit either a satirical or a romantic target. She sold Northanger Abbey to a bookseller cum publisher in 1803 where it languished on the slush pile, unpublished, for almost ten years. And there it would probably have stayed if Austen's brother Henry hadn't bought the book back after the death of his sister and brought it out posthumously as part of a series.

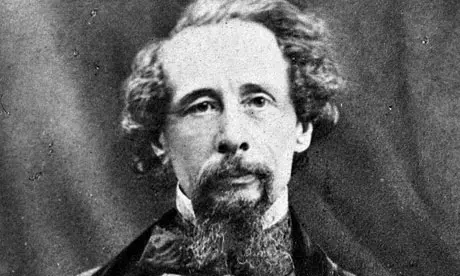

![]() Charles Dickens: Mr Nastypants

Charles Dickens: Mr Nastypants

Like Austen, Dickens was a writer so crammed with talent it practically oozed out of him like the cheese from an overfilled calzone. He wrote whole books as serialised installments, juggling plot and a huge cast of characters with the deftness of a circus act. And he was a campaigner, writing A Christmas Carol explicitly as a conscience nudger for the English middle classes. If YouTube had been around in Dickens’ day he would have had his own channel stuffed with Kony 2012 type videos exhorting people to buy rubber bracelets in support of orphan relief.

My Cherished Belief

Seduced by early exposure to his fiction, my image of Dickens owed a lot to one of his most lovingly drawn characters. Mr Fezziwig from A Christmas Carol is the epitome of the jolly paterfamilias - all mulled wine and good cheer. Eyes moist, I imagined Dickens lugging home a turkey the size of a Volkswagen for the Yuletide table, planting a kiss on his wife Catherine's cheek and tousling the heads of his applecheeked brood a la Jimmy Stewart in It's A Wonderful Life.

The Awful Truth

Far from being the perfect husband, Dickens decided in his early forties that his wife Catherine – loving, supportive and the mother of his ten children - was no longer fit for the job. Suffering a mid-life crisis straight from the pen of Updike, Dickens removed himself from the family home, sent complaining letters to all his friends about Catherine’s failings, forced them to pick his side if they wanted to stay his friend and set himself up with a younger and prettier woman. As for his children, his relationship with them was so distant that none of them had any idea that David Copperfield – famously based on his own early experiences of working in a blacking factory – was anything but fiction. Dickens had told his friends and publishers about his difficult childhood, but failed to share any of that with his own family.

![]() J D Salinger: Prolific But Mostly Crap

J D Salinger: Prolific But Mostly Crap

From the moment I first read A Catcher in the Rye I loved it with the exclusive, possessive passion the average fifteen year old reserves for what they fondly believe is a book written specially for them. For quite a long time, I actually believed Catcher was an autobiography, completely caught up in the idea that Holden, who seemed to think exactly the same way I did about the adult world and all its phoniness, couldn't be anything else but totally real (I was fifteen, catch me a break here). Who was this J D Salinger? I wondered, and why was his name on the cover of the book?

My Cherished Belief

Once I had reluctantly acknowledged that The Catcher in the Rye was fiction, I then persuaded myself (with some help from the rest of the world) that Salinger's classic wasn't only his crowning achievement, it was his sole achievement. For years I believed that Catcher was Salinger's only published work. I also believed that, in keeping with his visionary status, immediately after writing this single work of genius, Salinger had renounced the world and locked himself in a shed in which he stayed until he died, fifty years later. After all, I asked myself, isn't that what Holden would have done?

The Awful Truth

Salinger didn't stop writing after Catcher in the Rye. He just stopped writing good stuff. Apart from A Good Day for Bananafish - the story which preceded Catcher - the rest of his published work makes dreary reading. His last story, published in Salinger's preferred journal, the New Yorker, was universally panned. Even after that debacle, Salinger kept on writing every day, spending at least a couple of hours at his desk. What he produced never saw the light of day and we can only assume it was of the same quality as his later work. As for reclusiveness, Salinger certainly didn't court publicity, but equally he was no hermit. He lived openly, under his own name and made no special attempt to deter the curious. He wasn't a hermit. He wasn't anything like Holden. I bought Franny and Zooey and yet another legend bit the dust.

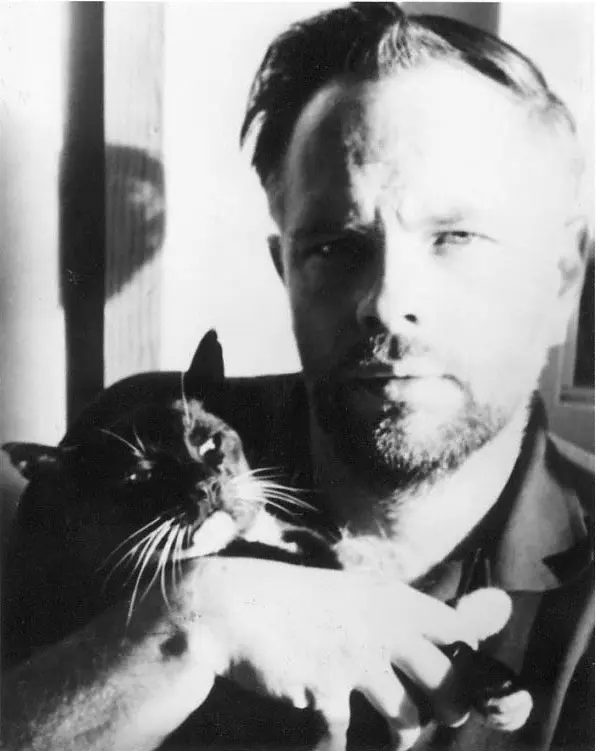

![]() Philip K Dick: Literary Wannabe

Philip K Dick: Literary Wannabe

Philip K Dick was also a prolific author, but unlike Salinger, didn't have the same concerns about exposing his work to the outside world. In a career spanning three decades, Dick published 44 novels and anywhere between 80 and 120 short stories (depending on which source you believe), all of them in the sci-fi genre.

My Cherished Belief

Exposed to the film Blade Runner at an impressionable age, like everyone else with a crush on Rutger Hauer, I scoured local libraries for copies of Dick's work, spending long hours acquainting myself with dystopian other-worlds when I should have been running after boys. As more films appeared based on Dick's work, I conceptualised the writer as a kind of High Guru of the fictional possibilities of artificial humans and memory implants. Philip K Dick, I told myself, was a man so immersed in the philosophical implications of the future that he ate, breathed and probably also shat science fiction the way Barbara Taylor Bradford does romance.

The Awful Truth

Far from being Robert Heinlein with a pulpier mien, Dick wrote sci fi strictly for the money. Not that he made much cash doing it: Dick spend his entire career a missed payment away from the repo squad and the truth is that even if he had done better at spinning a dime from his tales, he probably would have instantly grabbed the opportunity to leave the genre with the alacrity of a flea deserting the cooling body of its roadkill host. For Dick's aspiration was not to become rich, but to write literary fiction. The crushing disappointment of his life wasn't borrowing money from his more successful peers, it was that he never become the next Lawrence Durrell. It was only when all of his unsold literary novels were unceremoniously returned by his agency, that Dick finally committed himself to science fiction full time. Even then the dream didn’t die – over the years Dick repeatedly attempted to have his publishers market his books as mainstream, hoping for cross-over glory, but never with any success.

And finally…

![]() Stieg Larsson: Not Very Mysterious

Stieg Larsson: Not Very Mysterious

A journalist, well known for his crusading views but totally unheard of in the world of fiction, returns to his office one evening. In one hand a lit cigarette (he’s a hardened fifty-a-day man) in the other a take away hamburger for his dinner (he’s never met a vegetable he didn’t prefer to see in a waste disposal). He climbs the stairs because the elevator is on the fritz. He never reaches his destination. Struck down by a massive heart attack Stieg Larsson dies. He is just fifty years old.

My Cherished Belief

I don't quite know how this delusion lodged in my brain, but for quite some time, I believed that the Millennium trilogy, published after Larsson's death, was a chance discovery by his long term partner, Eva Gabrielsson. My version of events had Gabrielsson finding the manuscript tucked in a sock drawer or lurking on the back of his hard drive when she was finally ready to clear out his things. Unaware he had quietly been working away on the books in his spare time, she delivered them to a publisher friend for a verdict. The friend read them and spotted pure gold. And so the opportunity for the world to witness possibly the longest anal rape scene in movie history was born.

The Awful Truth

Sadly for my fevered imagination, a little research for another article soon put me straight. Larsson’s ambitions to break into fiction were long held and ones he had discussed repeatedly with his many contacts in the publishing world. He eventually secured a contract to write the series with the Swedish publishing company Norstedts, with a plan to produce an eventual ten installments. The reason that none of the books were published before his death (which may be the reason my addled brain came up with the 'surprise discovery' story) is that Larsson held onto the drafts until the third book was almost complete – perhaps because he conceived the story as one uninterrupted manuscript and edited them in that way.

How dull. Along with the conspiracy theories about Larsson’s death (rumors still fly that the books are lightly coated non-fiction and he was killed by a vengeful ex-Nazi), this is an addition to the Larsson legend that seems likely to persist, mainly because it’s so much more exciting than the truth. Something tells me that Larsson, conspiracy theorist par excellence, would approve of that.

And after all that sharing of how wrong I can be, I'm feeling a little sweaty and ashamed. Help me out here - tell me I'm not the only one. Did you have an image of an author which failed to live up to reality? Did you think JK Rowling was a man? Or that China Mieville's mother actually called him that? Put me out of my misery and please say you did...

About the author

Cath Murphy is Review Editor at LitReactor.com and cohost of the Unprintable podcast. Together with the fabulous Eve Harvey she also talks about slightly naughty stuff at the Domestic Hell blog and podcast.

Three words to describe Cath: mature, irresponsible, contradictory, unreliable...oh...that's four.

Jane Austen: Slush Pile Reject

Jane Austen: Slush Pile Reject

Charles Dickens: Mr Nastypants

Charles Dickens: Mr Nastypants

J D Salinger: Prolific But Mostly Crap

J D Salinger: Prolific But Mostly Crap

Philip K Dick: Literary Wannabe

Philip K Dick: Literary Wannabe

Stieg Larsson: Not Very Mysterious

Stieg Larsson: Not Very Mysterious