If you stick with the writing game long enough, someone may ask you to take a shot at characters and worlds invented by someone else. It could be a Star Wars story, or the next chapter in a novel some writer friends are passing around for fun. Snatching the proverbial baton from someone else can present some (fun) challenges unique to writing—and it’s potentially overwhelming if you’re not careful.

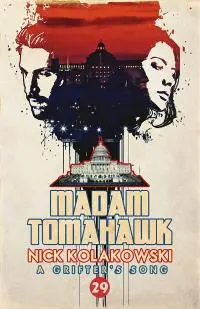

Last year, I was approached to write the next novella in the long-running “A Grifter’s Song” series for Down & Out Books. Each of the 29 (and counting) “episodes” follows Sam and Rachel, a pair of grifters who drift across the nation in search of lucrative scores. As you might expect from a crime-fiction series, they regularly run into trouble, including marks who’re deadlier than they appear, mobsters determined to take their heads, and garden-variety criminals looking to pull a double cross.

The series, which was created by Frank Zafiro, has attracted a diverse slate of writers over the years, including Hilary Davidson, Paul Garth, S.A. Cosby, Holly West, Eric Beetner, and Eryk Pruitt. Each of these writers brought their unique voice to the endeavor, but every episode also follows a core set of rules set from the very beginning, which leads to the first point: with anything like this, you need a series bible (also known as a story bible).

A series bible is a document (for some projects, it might even be a book) detailing all the relevant characters, story arcs, relationships, and much more. Some may describe what the writer can (and can’t) do with the material; with “A Grifter’s Song,” for instance, we couldn’t kill the leads, and we couldn’t do anything physically radical (like chopping off a hand). Whether you’re starting a series on your own or joining someone else’s long-running project in mid-stream, a series bible is essential. Don’t begin without one.

A series bible is a document (for some projects, it might even be a book) detailing all the relevant characters, story arcs, relationships, and much more. Some may describe what the writer can (and can’t) do with the material; with “A Grifter’s Song,” for instance, we couldn’t kill the leads, and we couldn’t do anything physically radical (like chopping off a hand). Whether you’re starting a series on your own or joining someone else’s long-running project in mid-stream, a series bible is essential. Don’t begin without one.

If you’re writing the next installment in a series or universe, it’s also important to read as many of the previous episodes/entries/books as possible, even if you only have a limited timeframe. Sure, you could get away with just reading the series bible—but you’ll miss all the universe’s nuances, which means you’ll miss the opportunity to weave in series-specific elements and easter eggs that will truly make the piece sing.

Getting the tone right is another challenge, one that can hinge on the “rigidity” of the underlying property. Every writer of James Bond novels after Ian Fleming’s death (I’m thinking of John Gardner, Raymond Benson, Anthony Horowitz, and others) has faced the unenviable task of incorporating the elements that fans expect (the megalomaniac villain, etc.) while freshening things up as much as they can. With the worst entries, you can sense the ghost of Fleming lurking just beneath the surface, contorting the narrative and voice into something the author doesn’t really want it to be.

But other writers carry it off—V. Castro’s recent Aliens: Vasquez has all the cinematic xenomorph action you’d expect, but it’s also a shining example of her unique voice, woven through with the same themes she’s tackled in her other, non-“Alien” books.

Fortunately, I had quite a bit of leeway with Madam Tomahawk, my contribution to “A Grifter’s Song.” I’d already written a series about grifters on the run (“Love & Bullets”), and so one of my main goals was making sure Sam and Rachel didn’t sound and act too much like Bill and Fiona, the wisecracking anti-heroes I’d created for my previous books. I also wanted to set a novel in Washington DC, where I grew up, but stay far away from Capitol Hill and the White House—funkier neighborhoods like Adams Morgan seemed a better fit for these grifters.

Did I succeed? That’s up to you. But if you ever get the chance to contribute to a series or shared universe, make sure you have the background materials you need, and that you’re comfortable meshing with everything that’s come before. It’s a real melding of the minds—potentially frustrating, sure, but also exhilarating.

Get Madam Tomahawk at Amazon

About the author

Nick Kolakowski is the author of the noir thrillers Boise Longpig Hunting Club and A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps. He's also an editor for Shotgun Honey, a site devoted to flash-crime fiction, and host of the Noir on the Radio podcast. His short work has appeared in Thuglit, Mystery Tribune, Spinetingler, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, and various anthologies. He lives and writes in New York City, and has zero desire to move to a stereotypical writer's cabin in the middle of nowhere.