LURID: vivid in shocking detail; sensational, horrible in savagery or violence, or, a guide to the merits of the kind of Bad Books you never want your co-workers to know you're reading.

Today marks the anniversary of the first publication in book form of Joseph Conrad’s novella, Heart of Darkness. This seafarer’s yarn about a journey up the Congo River in the 1890s was – as is usually the way – received with indifference by the public at the time, but has achieved classic status since. A century on, it regularly appears on ‘Best 100…’ lists, praised for its psychological depth, and as a visceral exposé of the damage wrought by colonialism.

Despite its brevity, this slim tome manages to be simultaneously epic, ambiguous, and highly controversial. The enigmatic villain at the center of Heart of Darkness, Kurtz, has been acclaimed as one of literature’s greatest monsters. The book has been adapted into movies, stage and radio plays and an opera. The story of Marlow’s odyssey upriver to meet the infamous Kurtz is echoed in novels by John Le Carré, V.S. Naipaul and Graham Greene, poetry by T.S. Eliot, and provides a referential framework for non-fiction by Nick Davies, Michaela Wrong and Sven Linqvist. With a student-friendly word count of less than 40,000 words, it has become a curriculum staple, the subject of a million awkward student essays.

Unfocused undergraduates struggling with Conrad’s labyrinthine sentences aren’t the only ones who hate on Heart of Darkness, however. In a 1964 interview with Playboy, Vladimir Nabokov dismissed Conrad as a writer “of books for boys”, and declared:

...I cannot abide Conrad’s souvenir-shop style, bottled ships and shell necklaces of romanticism clichés. In neither of those two writers can I find anything that I would care to have written myself. In mentality and emotion, they are hopelessly juvenile.[1]

Chinua Achebe was the book’s most vocal opponent, and his best-known work, Things Fall Apart, is a biting response. He called it “offensive and deplorable” and railing, in lectures, articles and in conversation, against Conrad, the “thoroughgoing racist”. He resented, above all, the depiction of Africa as the fabled ‘Dark Continent’, as:

…a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognizable humanity, into which the wandering European enters at his peril. Can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind?[2]

In some ways, it is indeed difficult to read Heart of Darkness in these postcolonial times. Yet it is possible to see beyond Conrad’s unthinking use of the n-word to his raw depiction of the evil that men do to a narrative authenticity that is still cutting edge. The ultimate unlikable protagonist, Marlow, is no great white savior of benevolent colonial myth: he’s a profit and thrill-seeking seaman, not a missionary. He observes, he feels inward distaste, but he makes no attempt to save anyone’s soul, not the Africans’, not his own, not Kurtz’s.

His experiences in country are framed as a story within a story, a technique necessary to give the reader at least some protective distance from the narrator’s gut-wrenching first person travails. A quintet of old friends wait on board the Nellie (“a cruising yawl”) for the tide to turn at the mouth of the River Thames, so they may make the return voyage to London. While they wait, Marlow, a former sea captain, tells a tale about the time he turned “fresh-water sailor”, piloting a steamer to “the farthest point of navigation and the culminating point of my experience.”

As Marlow recounts atrocity after abomination after outrage, his companions, also men who have “followed the sea” as their vocation, sit in respectful silence. They have undoubtedly profited from the same trade winds that took Marlow to the innermost reaches of the jungle, so perhaps they share some of the burden of his guilt? Beyond their reverent circle sits the landlocked reader, struggling to decide which of Marlow’s lurid narrative twirls are concoction, and which are straight-up reportage.

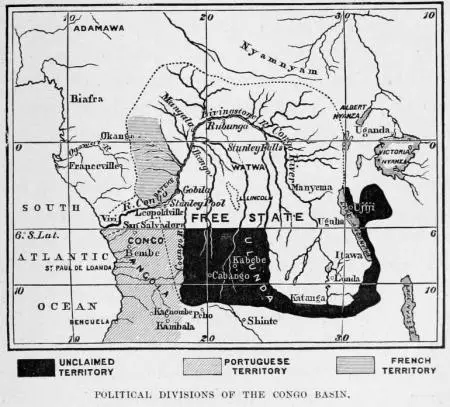

Therein lies the real horror of Heart of Darkness: it can be categorized under True Crime. In writing it, Conrad drew heavily on his personal experiences of a decade earlier, on the SS Roi des Belges, as she made her cautious way upstream from Kinshasa to Stanley Falls (Kisangani). Aged 33, Conrad was an experienced seaman, but he was repulsed by what he termed the “sordid instincts” of the ivory traders, and the devastation wrought on the people and the land in the name of profit. He wrote in a letter home “Everything here is repellent to me.”

‘To tear treasure out of the bowels of the land was their desire…’

Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost (1998) corroborates the depravity and corruption Conrad sailed into. King Leopold II of Belgium was the greediest of European monarchs, joining the scramble for African riches with sadistic gusto. He hired Welsh explorer, Henry Morton Stanley (he of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” fame) to claim the ‘Congo Free State’ as a colony – not for Belgium, but as his personal treasure chest.

Leopold never set foot in the region himself. Instead, he hired a small army of sociopaths, European-bred officials who would stop at nothing to strip the area of its natural ivory and rubber resources, and sat back, enjoying the gushing revenue stream. While his officials massacred ten million Africans in the name of plunder, Leopold lavished much of his profits on his mistress, Caroline Lacroix, a French prostitute who first caught his eye when she was sixteen – and he was 65. He spent so much of his ill-gotten gains on mansions, finery and travel with an entourage for his youthful paramour that the scandalized press dubbed her la reine du Congo.

‘Exterminate All The Brutes!’

While Leopold focused solely on the bottom line in Belgium, his officers in the field ran amok. At the time, Leopold, as part of his massive European PR campaign, described his employees as “all-powerful protectors” or “benevolent teachers” working selflessly towards the greater good (“the work of material and moral regeneration”). Hochschild identifies several real-life Kurtzes; men who, freed from European oversight, indulged in extreme barbarism without fear of penalty.

One of the candidates for Kurtzhood was Leon Rom, a Belgian soldier who, in his search for adventure, found himself in the right place at the right time. He arrived in the Congo in 1886, became district commissioner at Matadi, and then took charge of the murderous Force Publique, the Leopold-sponsored militia gangs who policed the forced labor system, and were responsible for making sure that villages met their — often outrageous — quotas for rubber and ivory. Those who did not supply enough rubber to feed Leopold’s greed were shot dead. The Belgian king gave his Force Publique bullets, but, so they didn’t squander them on hunting for food, demanded severed hands as proof they had been shot in his service.

In order to fill a basket of severed hands, soldiers dismembered the living. In order to placate soldiers and meet quotas, neighboring villagers would attack each other and top up their inadequate rubber offering to the king with limbs.

…The baskets of severed hands, set down at the feet of the European post commanders, became the symbol of the Congo Free State. ...The collection of hands became an end in itself. Force Publique soldiers brought them to the stations in place of rubber; they even went out to harvest them instead of rubber... They became a sort of currency. They came to be used to make up for shortfalls in rubber quotas, to replace... the people who were demanded for the forced labour gangs; and the Force Publique soldiers were paid their bonuses on the basis of how many hands they collected.

— Peter Forbath, The River Congo: The Discovery, Exploration and Exploitation of the World's Most Dramatic Rivers (1977)

Leon Rom presided over this gruesome trade without once questioning the idiocy or immorality of collecting severed limbs as tribute. He appeared to relish an execution aesthetic. He kept a gallows permanently erected in front of the station house at Stanley Falls and also decorated his flowerbeds with human heads – much as Kurtz surrounds his home with “heads on stakes”.

Inspiration for Kurtz’s delusional nature also surely came from Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, a British officer left in charge of the Rear Column of Henry Morton Stanley's Emin Pasha Relief Expedition in 1886. We shall never know if it was the sudden pressure of command, malaria, or even syphilis, but (Hochschild tells us):

...Major Barttelot promptly lost his mind. He sent Stanley's personal baggage down the river. He dispatched another officer on a bizarre three-thousand-mile three-month round trip to the nearest telegraph station to send a senseless telegram to England. He next decided that he was being poisoned, and saw traitors on all sides. He had one of his porters lashed three-hundred times (which proved fatal). He jabbed at Africans with a steel-tipped cane, ordered several dozen people put in chains, and bit a village woman. After trying to interfere with a native festival, an African shot and killed Barttelot before he could do more.[3]

Other members of this expedition also provided rich source material for Conrad. Tippu Tip was a notorious slave trader, who, when appointed Governor of the Stanley Falls district by Leopold, made a fabulous fortune locating and selling ivory – Kurtz’s forte. The leader of the expedition, Henry Morton Stanley, styled himself as a journalist, much as Kurtz, perpetually scratching at his report for the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs, was wont to do.

'The wilderness had found him out early'

Conrad peoples his novella with minor characters, the nameless agents of the Company, who are also drawn from his personal experience. When Marlow turns up for his pre-employment medical in Brussels, he is treated as cannon fodder, as yet more youthful ambition to sacrifice to Leopold’s cause. The examining doctor declares Marlow’s pulse to be “good for there”, and in the interests of phrenology, measures his skull dimensions. The good doctor is clearly of the opinion that the Congo attracts a certain type (“’Ever any madness in your family,’ he asked, in a matter-of-fact tone”), and from experience knows that Company employees are unlikely to pass through his office a second time, because of the “changes [that] take place inside, you know”.

Once ‘up country’, Marlow encounters many Europeans engaged in “the merry dance of death and trade”. None of them exhibit the same levels of insanity as Kurtz, but from the suicidal Swede, to the Company accountant who insists on dressing like a “hairdresser’s dummy” in the jungle humidity to the bearded boiler-maker to the arrogant members of the Eldorado Exploring Expedition, they are all, clearly, quite, quite mad. Kurtz’s descent into delirium doesn’t happen in a vacuum: he is surrounded (and enabled) by similarly unhinged individuals. None of Kurtz’s fellow officials think he is mad. Indeed, the consensus is that Kurtz will be promoted to the glorious post of General Manager. All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that these good men do nothing. They put up no resistance to moral and spiritual decay, ignoring the rising tides of darkness lapping at their own hearts.

Conrad catalogues their collective madness quite clinically, diagnosing a specific psychosis that would blight the coming century. The unthinking savagery prevailing among Company officials in Heart of Darkness is echoed in the trenches of the First World War, the rise of the Third Reich, Stalinist purges, the My Lai massacre, and in ethnic cleansing and mob attacks of every stripe. Writing a century after Conrad, Dipak K. Gupta likens collective madness to “the primordial feeding frenzy of sharks”, defining it as:

…when a group of people working for a shared ideology know of no boundaries to achieve their shared goals – legality, civility or even the most basic humanity. In times like these, we kill other human beings, not because they have done something personally to offend us, but because their very existence as members of a particular group poses an affront to us. We form bonds in our shared hatred with those similar to us, and spare nothing to inflict pain and punishment on the odious others…

— Path to Collective Madness: A Study in Social Order and Political Pathology (Praeger, 2001)

This cuts to the core of Heart of Darkness, and crystallizes the mass insanity that so fascinated and repelled Conrad. In writing about the grim reality of colonialism, in drawing so heavily on true life and crime experiences, he crafted a sinister moral fable that still resonates in our own time. We see it played out amongst the rapacious bankers of Wall St., or in the workings of pernicious corporate cultures from Big Ag to Global Oil. Who knows what atrocities are being committed in Indonesia's jungles in the name of our own era's rubber, palm oil? It's no surprise that Conrad's nineteenth century traveler’s tale continues to be popular with twenty-first century readers, and continues to provide the inspiration for new texts (a new movie version of the book, set in space, Into Darkness, is slated for release in 2016). Heart of Darkness stands as further proof, if we needed it, that the most disturbing and enduring horror stories are almost always based in truth.

[2] Achebe, Chinua. "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's 'Heart of Darkness'" Massachusetts Review. 18. 1977

[3] King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Mariner Books, 1998) p.98

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .