LURID: vivid in shocking detail; sensational, horrible in savagery or violence, or, a twice-monthly guide to the merits of the kind of Bad Books you never want your co-workers to know you're reading.

From the beginnings of humanity, we’ve struggled to find our place in this wondrous and confusing universe. It’s in our nature as a species to question, to seek, to theorize, but on our millennia-long quest for knowledge about ourselves and our surroundings, not everything we’ve learned has been to the benefit of all humankind.

Sometimes knowledge comes at a terrible price; what looks like an advance might be a huge step backwards. Tools for creation can be converted into seeds of mass destruction. A short-term elixir can evolve into a long-term poison. It’s not surprising we’re so conflicted about the relationship between science and society. That’s why we need Mad Scientist stories, now and in centuries past. Although technology is always changing, our fear of it remains the same. Manifesting that fear through horror fiction is our way of keeping the excesses of laboratory lunacy reined in, at least on the pages and screens of our shared nightmares.

Since the Age of Reason, we’ve shown outward fealty to Science, organizing our civilization around scientific principles from health to agriculture to manufacture to transport. Whatever scientists decree, we do. And we resent it. So, simultaneously, we relish fiction that functions as a scientific cautionary tale, anything that shows hyperbolized scientists, with crazy haircuts, over-reaching themselves with horrific consequences – the more grotesque and outrageous those consequences the better. It seems there’s still a pitchfork-waving villager inside every one of us, ready to break out the flaming torches at the first sign of an experiment gone wrong.

Mad Scientists are complex figures, anarchist outsiders paradoxically yearning for the adulation and acceptance from conventional society that a major scientific breakthrough might bring. From Dr. Faustus to Mrs. Coulter, they just want to be loved. They also represent our last stubborn belief in magic, the scientist as illuminatus, privy to secrets from beyond the veil. The Mad Scientist master narrative tends to revolve around alchemy, rather than specific branches of physics, chemistry or biology.

Their stories follow a consistent paradigm: visionary thought is punished as hubris, the offending scientist is nullified (usually by some nice-but-dim anti-intellectual), social mores are re-established, but some hint of the aberrant creation remains, in limbo, a threat to be reactivated should any presumptuous individual dare to indulge such delusions again.

One of the earliest Mad Scientists is Prometheus, the Titan condemned to a state of perpetual agony (thanks to the eagle munching on his liver) after he stole fire, that first great technological advancement, from the gods and gave it to men. Prior to that, Prometheus attracted Olympian ire by figuring out a way to cheat Zeus on the meat content of sacrificial cattle, and by teaching humans the basic scientific principles of mathematics, agriculture and medicine. He’s an important figure in ancient Greek mythology, grasping for forbidden knowledge because he believes that it’s vital to human development, and that the up side always outweighs the down. He’d agree with Arthur C. Clarke that “the only way to discover the limits of the possible is to go beyond them into the impossible.”

Before the twentieth century, Mad Scientists were shown as challenging the natural, divinely decreed (and usually binary) order of things. The first five on my list definitely reached for the impossible. Dr. Faustus toyed with damnation vs. salvation. Dr. Frankenstein aimed to break down the boundaries between Life and Death. Dr. Jekyll wanted to test the moral line between good and evil, Dr. Moreau the biological division between animals and humans. Drs. Dyer and Danforth meddled with ancient fortifications dividing human from alien beings. But these men are a lost breed. The coming of the machine age made technological progress less about the ‘Eurekas’ from individuals standing on the shoulder of giants, more about teamwork and lab dollars.

The Classics

![Dr. Faustus]() 1. Dr Faustus (The Tragical History of the Life And Death of Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe 1604)

1. Dr Faustus (The Tragical History of the Life And Death of Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe 1604)

In the early 16th century, there was only one science for madmen: alchemy. In its heyday, it didn’t just involve turning lead in to gold, conferring immortality, creating homunculi or raising the dead, but was also about opening up communication channels with angels and devils. For his memorable protagonist, Marlowe blended the German legend with biographical details from his contemporary John Dee, master alchemist and Elizabeth I’s astrologer. As the play opens, Faustus, “glutted now with learning’s golden gifts”, claims to know everything in terms of the usual disciplines of logic, law, divinity and medicine, and vows to turn to the “metaphysics of magicians”. This extra level of knowledge will make him a demi-god. Enter Mephistopheles, who promises to teach him everything he needs to know. There’s just one small price to pay: eternal damnation.

![Dr. Frankenstein]() 2. Victor Frankenstein (Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley 1818)

2. Victor Frankenstein (Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley 1818)

By the early 19th century, alchemy was no longer de rigeur. Unfortunately, the young Victor Frankenstein doesn’t get the memo. As a teenager he chances upon the work of uber-alchemist Cornelius Agrippa in the family library and, unaware that “the principles of Agrippa had been entirely exploded and that a modern system of science had been introduced which possessed much greater powers than the ancient,” he devours the volume, and tucks into Paracelcus and Albertus Magnus too. When he arrives at the university of Ingolstadt, he’s more than a little upset to be told that he needs to study dull in comparison chemistry instead. Harking back to a golden era “when the masters of the science sought immortality and power”, he decides to undertake a little research project of his own. And the rest is literary history.

![Dr. Henry Jekyll]() 3. Dr. Henry Jekyll (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson 1886)

3. Dr. Henry Jekyll (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson 1886)

Dr. Henry Jekyll’s experiments with an alter ego are also vaguely alchemical in nature. His avowed goal is to create a tincture that could control and shake “the very fortress of identity”, but in his confession he is deliberately vague about the ingredients. All he will say is that he purchases large quantities of “a particular salt” he hypothesizes is key to transformation, and then tests it on himself. The drug induces “a grinding in the bones, deadly nausea, and a horror of the spirit that cannot be exceeded at the hour of birth or death.” It gives Jekyll access not to higher knowledge, but to a coarser self:

“I felt younger, lighter, happier in body; within I was conscious of a heady recklessness, a current of disordered sensual images running like a millrace in my fancy, a solution of the bonds of obligation, an unknown but not an innocent freedom of the soul. I knew myself, at the first breath of this new life, to be more wicked, tenfold more wicked, sold a slave to my original evil; and the thought, in that moment, braced and delighted me like wine.”

Although the experiment initially seems like a success, it doesn’t take long before this monstrous alter ego, Mr. Hyde, is on a murderous rampage through London, and Jekyll is faced with the perennial Mad Scientist problem of damage control.

![Dr. Moreau]() 4. Dr. Moreau (The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells 1896)

4. Dr. Moreau (The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells 1896)

Dr. Moreau flees London after the cruelty of his animal experiments shock even a Victorian nation, and winds up on a remote island where he can vivisect to his heart’s content. The action of the novel introduces us, via a shipwrecked sailor, Prendick, more than a decade into Moreau’s bizarre experiment to turn animals into humans (not, as Moreau takes pains to explain, turning humans into animals, which would be barbaric). Prendick finds himself an unwelcome houseguest in the monstrous menagerie, worrying that he might be next under Moreau’s knife and wake up one morning as a hybrid. His presence causes chaos on the island, and, inevitably brings the project to a visceral end. Wells dismissed his novel as “an exercise in youthful blasphemy”. In it he implies that Moreau’s work is less about genuine scientific discovery and more about the “because I can” of a delusional megalomaniac who wants to be king of the Beast Folk. However, we currently live in a world where genetic hybrids like spider-goats and camel-llamas are part of agricultural reality, so Moreau may well be having the last laugh.

![At The Mountains of Madness]() 5. Danforth & Dyer (At The Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft 1931)

5. Danforth & Dyer (At The Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft 1931)

H. P. Lovecraft’s stories are stuffed with isolated intellectuals obsessed by prohibited knowledge, often of an alchemical nature (The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, The Dreams In The Witch House), and his creations include Dr. Herbert West, who out-delusions both Frankenstein and Moreau when it comes to playing God with human body parts. However, in 1931 Lovecraft delivered a different type of Mad Scientist to pulp fiction fans; the fatally self-aware prophet. When geologist William Dyer embarks on a Miskatonic University expedition to the Antarctic, he has no idea that it will bring him into contact with an ancient, alien civilization. However, when he realizes that his colleagues have been eviscerated and an entire encampment destroyed by a couple of defrosted Elder Things, his first reaction is not to, as any sane scientist might, turn tail and flee. Instead, he and his Poe-quoting, Necronomicon-reading colleague, Danforth, hotfoot it into the heart of the creatures’ surreal city, a “monstrous tangle of stone dark stone towers”, characterized (in uniquely Lovecraftian terms) by “infinite bizarrerie, endless variety, preternatural massiveness, and utterly alien exoticism.” They know they shouldn’t be there, but they keep exploring until they come face to face with the ultimate nightmare being, a Shoggoth. As they manage, against the odds, to escape, Danforth glances back and witnesses a “final horror” that drives him to the point of complete mental breakdown. Dyer couches the account of his experiences as a dire warning (“I would not speak of them now but for the need of heading off that Starkweather-Moore Expedition”), but his claims to logic and sanity don’t fool the reader. We know only a madman would have gone into the mountains in the first place.

The Moderns

World War Two proved to be a watershed for science. Before Oppenheimer and Mengele’s experiments became international headlines in 1945, Mad Scientists tended to be eccentric individuals, their private laboratories fuelled by hereditary wealth. After the horrors of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the atom bomb, it became apparent that governments were in on the game, and the most extreme scientific madness was funded by research grants. The post-WW2 Mad Scientists on this list work for clinics and corporations; Dr. Vaughan starts out at a TV station, and Mrs. Coulter’s paymasters are the Catholic Church, Inc.

Mengele, Auschwitz’s ‘Angel of Death’, performed experiments on human subjects that would have made Drs. Moreau and West nauseous. There was no rhyme or reason to his in vivo investigations into twins, dwarves, Roma or pregnant women; he cut them up - usually without anaesthesia - and killed them anyway. Survivor Alex Dekel said “The patients did not count. He professed to do what he did in the name of science, but it was a madness on his part." After the reality of Mengele became part of cultural consciousness, Mad Scientists in fiction came to be cut from a different, more authentic cloth.

![Dr. Josef Mengele]() 6. Dr. Josef Mengele (The Boys From Brazil by Ira Levin 1976)

6. Dr. Josef Mengele (The Boys From Brazil by Ira Levin 1976)

Ira Levin went straight to the source for his mad scientist. More than thirty years after Mengele disappeared to South America, he still cast enough of a shadow to drive this narrative about ongoing Nazi experiments into human cloning. Logically, a loyal member of the Third Reich is going to clone the Führer, and the plot concerns the discovery by Nazi hunter, Yakov Liebermann, that there are almost a hundred replica Hitlers growing up worldwide. Although Mengele’s got the biology right (all the clones look eerily similar, with licks of dark hair and hypnotic blue eyes), he doesn’t want to leave the nurture angle up to chance and has had the clones adopted into family circumstances similar to Hitler’s own. This means, at the age of thirteen, the boys all have to lose their father. Liebermann goes toe-to-toe with Mengele (many a frustrated Nazi hunter’s dream), but destroying the Mad Scientist in this scenario doesn’t necessarily equate to destroying his plans for world domination.

![Joyce Carol Oates]() 7. Dr. Karl Pedersen (Wonderland by Joyce Carol Oates 1971)

7. Dr. Karl Pedersen (Wonderland by Joyce Carol Oates 1971)

Luckless teenager, Jesse Vogel, escapes death alongside the rest of his family at the business end of his father’s shotgun only to be adopted into the well-padded bosom of the Pedersens. Dr. Karl, his wife Mary, son Frederich and daughter Hilda, are all obese - and Oates’ prose invokes their waistlines expanding even further during the course of the narrative – their excess body fat cushioning them from the outside world and each other’s bottomless misery. Frederich is a musical prodigy, Hilda is a mathematical mastermind, Mary is an alcoholic, all of them orbiting round the whims and madness of Karl who sees them as nothing more than test subjects for his bizarre medical philosophies. He views the unfortunate patients at his clinic in exactly the same way (“Once a patient has come to him, he believes the patient is his. The patient’s life is his. He owns the patient, he owns the disease, he owns everything. Oh, he’s crazy”). Despite his small town status, Pedersen’s delusions (as well as destroying his wife’s mind he wants to patent various germ warfare devices) are dangerous and destructive, and he’s one of Oates’ most chilling creations.

![Hell House]() 8. Emeric Belasco (Hell House by Richard Matheson 1971)

8. Emeric Belasco (Hell House by Richard Matheson 1971)

Hell House has featured as a Lurid pick before. The entity at the center of the haunting, Emeric Belasco, also serves as a paradigmatic Mad Scientist. "His mind may have been aberrant, but it was brilliant too... He could master any subject he chose to study. He spoke and read a dozen languages. He was versed in natural and metaphysical philosophy. He'd studied all the religions, cabalist and Rosicrucian doctrines, ancient mysteries. His mind was a storehouse of information, a powerhouse of energy...a charnelhouse of fancies." After being left ten and a half million dollars by his father, he builds a mansion in 1919, invites a bunch of houseguests, and subjects them to a series of cruel psychological experiments in order to discover how low human beings can really go. By July of 1929, Belasco is presiding over "a group of drug addicted doctors [who] started to experiment on animals and humans, testing pain thresholds, exchanging organs, creating monstrosities." By November, everyone's dead - but Belasco's body is never found. Trumping all the others on this list, he's discovered a way to continue his bizarre experiments even after death.

Hell House is a case of 'set a Mad Scientist to catch a Mad Scientist'. The equally barking Dr. Lionel Barrett, a physicist dedicated to investigating "the undiscovered mysteries of the human spectrum, the infrared capacities of our bodies, the ultraviolet capacities of our minds" wants to test the phosporescent tubes of his Reversor (a kind of ghost sucking machine) on Belasco's shade, and the stage is set for a Mad Scientist battle royale. Although Matheson situates Belasco’s Sadean manipulation of others in the decadence of the 1920s, his attitude is pure 1970s, part of the same scientific context as the Milgram and Stanford experiments. If he were alive today, Belasco would be a big fan of reality TV, especially Big Brother.

![Elias Koteas in 'Crash']() 9. Dr. Robert Vaughan (Crash by J.G. Ballard 1973)

9. Dr. Robert Vaughan (Crash by J.G. Ballard 1973)

Dr. Vaughan is a demented figure from the get-go, obsessed with organizing his death-by-head-on-car-crash-with Elizabeth Taylor. “On a pair of scarred and uneven legs repeatedly injured in one or other vehicle collision, the harsh and unsettling figure of this hoodlum scientist came into my life at a time when his obsessions were self-evidently those of a madman.”

Although he’s wholly a product of the automobile age, he’s also a throwback to the aristocratic, educated arrogance of the nineteenth century madmen: “Literate, ambitious and adept at self-publicity, he was saved from being no more than a pushy careerist with a Ph.D. by a strain of naive idealism, his strange vision of the automobile and its real role in our lives.” He’s insane, but visionary, able to gather disciples who share his belief in the orgasmic power of metal penetrating flesh and the desire to create human-automobile hybrids. He’d be entirely at home on the island of Dr. Moreau.

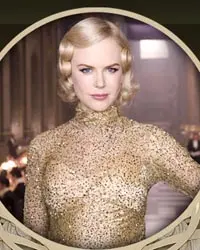

![Nicole Kidman as Mrs. Coulter]() 10. Mrs. Coulter (Northern Lights /The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman 1995)

10. Mrs. Coulter (Northern Lights /The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman 1995)

The only woman on this list embodies both the classic and modern Mad Scientist traits. Marisa Coulter presents as a sophisticated, even glamorous scholar, one of the few female members of the Royal Arctic Institute, able to explain to a bemused Lyra that five planets orbit the sun. She’s very dangerous when roused (“Mrs. Coulter seemed to be charged with some kind of anbaric force. She even smelled different: a hot smell, like heated metal, came off her body”). As well as being a handy member of any team setting out to explore the Mountains of Madness, she would have been at home at a Nazi cocktail party, thanks to her experience with the General Oblation Board. Like Mengele, she had no qualms about using children as subjects for experimentation (investigations into the barbaric and usually fatal process of “intercision”) and like Faustus, she ultimately comes to regret the pact she’s made with the Devil in the cause of furthering her alchemical insight.

In 2012, Prometheus is the title of the eagerly anticipated Ridley Scott movie that started out as an Alien prequel but, like so many mad science experiments before it, mutated into something… else. In it, Scott revisits the most enduring Mad Scientist tropes – the overwhelming thirst for forbidden knowledge, the disdain for individual safety, the miscalculation of consequences, the Holymotherofgodwhatthefuckwasthat? moment of truth, and the frantic attempt at negation or reversal of the failed experiment before the whole of humanity pays the price. It wears the literary influences listed below on its blockbuster-budget sleeves. A must-see horror movie, it’s the monstrous child of these many fathers. Mad Scientists obviously still rule our imaginations.

Who are your favorite Mad Scientists, both classic and modern? I could only get ten on the list. Over to you, LitReactors…

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .

1. Dr Faustus (The Tragical History of the Life And Death of Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe 1604)

1. Dr Faustus (The Tragical History of the Life And Death of Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe 1604)

2. Victor Frankenstein (Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley 1818)

2. Victor Frankenstein (Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley 1818)

3. Dr. Henry Jekyll (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson 1886)

3. Dr. Henry Jekyll (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson 1886)

4. Dr. Moreau (The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells 1896)

4. Dr. Moreau (The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells 1896)

5. Danforth & Dyer (At The Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft 1931)

5. Danforth & Dyer (At The Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft 1931)

6. Dr. Josef Mengele (The Boys From Brazil by Ira Levin 1976)

6. Dr. Josef Mengele (The Boys From Brazil by Ira Levin 1976)

7. Dr. Karl Pedersen (Wonderland by Joyce Carol Oates 1971)

7. Dr. Karl Pedersen (Wonderland by Joyce Carol Oates 1971)

8. Emeric Belasco (Hell House by Richard Matheson 1971)

8. Emeric Belasco (Hell House by Richard Matheson 1971)

9. Dr. Robert Vaughan (Crash by J.G. Ballard 1973)

9. Dr. Robert Vaughan (Crash by J.G. Ballard 1973)

10. Mrs. Coulter (Northern Lights /The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman 1995)

10. Mrs. Coulter (Northern Lights /The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman 1995)