LURID: vivid in shocking detail; sensational, horrible in savagery or violence, or, a guide to the merits of the kind of Bad Books you never want your co-workers to know you're reading.

Human sexual desire is a battlefield. Across cultures, we’ve taken what should be the relatively level territory of pleasure/reproduction and barb wired it around with laws, morals, norms, ideals, emotions and customs, loaded it with social values, and dug it deep into power structures and family hierarchies. The rules of engagement shift from nation to nation, from year to year, from trend to trend: keep up with the changes or face shame and exclusion. Put a foot wrong and it will all blow up in your face.

Nowhere is the crossfire more intense than in the area of human development known as pubescence, the three to four year window during which a child matures physically – although mentally and emotionally they are still a long way off adulthood. It’s a downright perilous place to be. The individual possesses functioning equipment and the urges that propel it, but lacks control mechanisms. Often, they have no specific knowledge of the minefields ahead other than the vague “Here Be Dragons” of contemporary Sex Ed.

Their confusion raises a particularly thorny question. How is the rookie to be trained? Through furtive fumblings with equally confused and callow peers (the blind leading the blind), or through an association with a more mature initiate? Historically, we’ve leaned towards the latter, via long-standing traditions such as pederasty (an intense – not necessarily sexual – relationship between an adult male and an adolescent boy) and child brides offering social and legal sanction to the practice.

The Age of Consent

For centuries, sex was only permitted within the confines of marriage, but marriageable age was usually placed at, or just before, the onset of puberty. The high value placed on female virginity coupled with infant mortality rates and the likelihood of dying in childbirth meant it was wise to start breeding sooner rather than later. For most of Western Europe, and for the United States as they came into being, this was around 10-12 years of age. It was legal to take a bride below that age, but generally accepted that intercourse would not take place until after her first period.

It wasn’t until the notion of childhood (and childhood innocence) as a separate state of being took hold in the 19th century that thinking changed. English campaigners against child prostitution sought to make it a crime to have sex with young girls and succeeded in raising the age of consent – when an individual is deemed to understand the moral and biological consequences of their decision to have sex – to 16 in 1885. It became a crime, statutory rape rather than merely a breach of etiquette, to instigate sexual relations with an underage partner, boy or girl, and this legal principle was gradually adopted across most of the rest of the world. Current limits range from 13 (Japan and Argentina) to 21 (Bahrain).

The idea of a buffer zone between the onset of puberty and the date when an adolescent was emotionally ready to have sex has its roots in this moral crusade, but 20th and 21st century scientific research into adolescent sexuality supports the concept. There can be horrible physical consequences for a pubescent girl subjected to pregnancy and childbirth too soon (such as elevated risk of obstetric fistula) and the babies they bear are more likely to have a low birth weight and die within the first year. For both sexes, early sexual activity can increase the likelihood of risky behaviors that lead to STDs and unplanned pregnancies.

There are also mental health issues. When the pubescent engages in sexual activity with an older partner, there’s likely to be an uneven distribution of power, which means a predator/victim dynamic. Where harm is done, the youngest, most vulnerable partner will bear the brunt of the damage.

Despite my best efforts, I am always the one who gets fucked. It won’t ever be any different, some things don’t change — I suppose I have to learn to enjoy it. — A.M. Homes The End of Alice

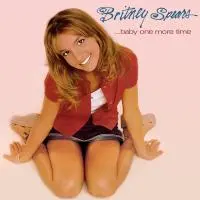

Yet, despite the global shift towards protecting young adolescents from the worst excesses of sex, we can’t seem to seem to relinquish the paradigm that young = desirable, and that the youngest are the most desirable of all. While pedophilia (sexual interest in children) is still a rigorously upheld taboo, it’s more acceptable (in advertising, music videos, TV shows, and on fashion runways) to flirt with hebephilia, attraction towards 11-14 year olds. Hello, young Britney Spears.

Yet, despite the global shift towards protecting young adolescents from the worst excesses of sex, we can’t seem to seem to relinquish the paradigm that young = desirable, and that the youngest are the most desirable of all. While pedophilia (sexual interest in children) is still a rigorously upheld taboo, it’s more acceptable (in advertising, music videos, TV shows, and on fashion runways) to flirt with hebephilia, attraction towards 11-14 year olds. Hello, young Britney Spears.

Look, But Don’t Touch

We persist in sexualizing our emerging teens, offering them carnal role models, suggestive clothing, eroticized entertainment and easy access to porn. We encourage them to dress up, act out and work it, bitch, without clearly explaining the rules of the game, the paradoxes inherent in gender double standards, the intricacies of rape culture, slut shaming, victim blaming, etc, etc, etc. This gets confusing for grown ups too, as the lines blur between YA and adult fiction, and hit movies increasingly feature a teen protagonist represented as ‘kinda hot’. Whereas the law is clear about underage sexuality, our culture is not – hence the proliferation of dubious Harry Potter slashfic.

Our post-Puritan society is reluctant to talk about sex, and is especially leery about speaking of sexual preferences that push boundaries – legal and moral – or challenge accepted mores. When news stories of adult/pubescent relationships surface, we take a prurient interest in the details, express shock and outrage, then move on, titillated maybe, but not too much. We can’t bear to look too closely. It takes an exceptionally brave writer – and reader – to engage with the scenario, to hold up a dark mirror to their own repressed desires, and to climb inside the mind of the predatory hebephile.

The few writers who have been brave enough to boldly go there have produced some of the most challenging transgressive fiction of the past sixty years. Inevitably, these books are lurid cautionary tales, ending in imprisonment or death for the protagonists. It’s one thing to delve into the thought processes of a kiddy fiddler for 300 pages, quite another to endorse them sailing off into a HEA sunset at the end. Yet there has to be empathy for reader engagement. The author must find points of compatibility between the hebephile and us, navigating some very sticky territory indeed between understanding and approval.

Lolita, or The Confession of a White Widowed Male

This then is my story… It has bits of marrow sticking to it, and blood, and beautiful bright-green flies. At this or that twist of it I feel my slippery self eluding me, gliding into deeper and darker waters than I care to probe.

The granddaddy of this oeuvre is Vladimir Nabokov’s classic, the elegant memoir written from accused child rapist Humbert Humbert to his defense attorney in an attempt to explain the extraordinary circumstances surrounding his relationship with one Dolores “Lolita” Haze, aged 12.

Nabokov dances around his novel’s salacious nature from the top. In the introduction, ostensibly written by the editor, “John Ray, Jr., Ph.D”, he reassures the reader that “not a single obscene term is to be found in the whole work”, but, in the very next sentence, promises “scenes that a certain type of mind might call “aphrodisiac””. He sets up Humbert, who will be the notably unreliable narrator, as “a demented diarist… a shining example of moral leprosy”. He declares a high-minded intent, that bringing this account of “the wayward child, the egotistical mother, the panting maniac” to the public’s attention is for wholly educational purposes:

These are not only vivid characters in a unique story: they warn us of dangerous trends; they point out potent evils. “Lolita” should make all of us parents, social workers, educators, apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bring up a better generation in a safer world.

By turns sad, hilarious, poignant and chilling, Lolita is the gilded and contradictory self-portrait of a monster (“You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style”). Nabokov’s deftness with language permits Humbert to be simultaneously locked into denial and disarmingly candid. Humbert is happy to explain exactly what he did, and how it made him feel, but he won’t admit that his actions are irredeemably, irrevocably wrong.

Humbert’s hypothesis is convoluted. He starts out by suggesting that the coitus interruptus experienced with his first love, Annabel, followed by her death a short while later from typhus, arrested his sexual development and pinned his desires to a single, pubescent spot. So far, so Poe. Then he introduces the idea that

Between the ages of nine and fourteen there occur maidens who, to certain bewitched travelers, reveal their true nature which is not human, but nymphic (that is, demoniac), and these chosen creatures I propose to designate as “nymphets”.

Never fear, not all 9-14 year-old girls are slutty little demons out to bring good men down. Just the ones who possess “certain mysterious characteristics, the fey grace, the elusive, shifty, soul-shattering, insidious charm”. And not all men are susceptible:

You have to be an artist and a madman, a creature of infinite melancholy, with a bubble of hot poison in your loins and a super-voluptuous flame permanently aglow in your spine…

Humbert uses this belief that he and Dolores are semi-mythical creatures to put their connection beyond the reach of common sense – or the long arm of the law. He depicts the ruthless pursuit of his chosen nymphet as a dance with Destiny, a journey written in the stars, rather than seeing it as textbook victim-grooming. He fears above all else seeming gripped by a sordid desire.

Thanks to Nabokov’s masterful control over the material, the reader entertains no such illusions. While Humbert gets tangled in his unfurling fantasy, we watch in clear-sighted horror as his machinations destroy Lolita’s peace of mind and sense of self, leaving her as irrevocably damaged goods.

Nabokov’s creation has maintained its stature over time not just because it is brilliantly written, but because Humbert is perpetual. His pompous self-justification lurks within every successive sexual predator case to make headlines. Yet, thanks to Lolita, we know his particular brand of “potent evil”. We can see his delusions behind the eyes of every Warren Jeffs or Raul Ochoa or Phillip Garrido. And, once identified, he can no longer hide.

The End Of Alice

More than forty years after the publication of Lolita, award-winning novelist A.M. Homes waded into the hebephile debate with The End Of Alice. While Lolita is draped in excuses and ellipsis, as Humbert denies denies denies, The End of Alice presents its sexual predators in brutal full frontal, challenging the reader to look, and then look away.

Homes acknowledges her debt to Lolita, but, in 1996, could go to dark places inaccessible to an author hoping for mainstream publication in 1955. Her equally unreliable narrator, Chappy, has been in jail for 23 years for the murder of another twelve year-old, the titular Alice. This “old and peculiar man, who has been locked away too long, punished for pursuing a taste his own” exists in a blur of fantasy, repressed memories, home-cooked narcotics and prison rape. Unlike Humbert, Chappy’s had 23 years to sit and contemplate his crime, and his sanity is riddled with cracks as a result.

He’s achieved a certain kind of notoriety – among tabloid journalists, law students and psychiatrists – and is used to receiving fan mail, so it’s not altogether a surprise when he receives a letter from an unnamed 19 year-old college student. While she’s a little old for his tastes, he’s delighted to discover she’s chosen him as confidante and advisor for her scheme to seduce a twelve year-old boy.

And so the elder predator grooms the younger, reveling in her epistolary descriptions of the techniques used to entrap the boy (tennis lessons!). Her obsession with the much-younger Matthew seems harmless, if weird, up to a point, that point being the fabled moment when she pulls a fresh scab from his knee and slips it

…into her mouth. He shudders. She is eating him. He’s never seen anything like it. His eyes roll up into his head; he falls back onto the bed.

Fainted. Out for the night.

The girl’s accounts of her experiences trigger memories of Chappy’s own exploits, rooted in the stark sexual abuse he experienced as a child – another infamous scene in the novel involves Chappy’s mother grievously misusing him in a bathtub. Like Humbert, Chappy blames his victim, insisting that she seduced him, tying him to the bed and jumping into the saddle (“With no warning she is down on me, unforgivably on me, riding me like an experienced equestrian”) – implying that his only crime is his inability to resist.

Nabokov’s elegant prose sugarcoats Humbert’s iniquity. Homes’ blunter style forces us to consume Chappy raw, scabs and all. Even reading to the final page is an act of uncomfortable complicity; empathy forced to its outer limits. It’s difficult to engage with the psychological morass that is the man, but reading is our only route to understanding. The End Of Alice, like all the best Bad Books, takes you on a ride to places you couldn’t, wouldn’t, shouldn’t ever otherwise go.

What Was She Thinking?/Notes On A Scandal

Zoe Heller’s 2003 take on the subject filters hebephilia through a genteel chattering class lens. Heller eschews any talk of mythological nymphets, destiny, or redemption, and sets her story firmly in the petty here and now. There’s less of a focus on the eroticized youth, more emphasis on the idiocy of the middle-aged woman who mistakes hormonal lust for genuine desire.

Heller’s unreliable, predatory narrator is a middle-aged woman: Barbara is in her early sixties, a cynical, close-to-retirement spinster teaching at a London comprehensive. Outwardly she’s respectable, upstanding, law-abiding. Inwardly, as we rapidly discover, she’s a seething mass of malevolence, jealousy, and insecurity, a predator waiting to strike.

Although she has a penchant for younger women, Barbara is not the hebephile in this cautionary tale: that honor falls to Bathsheba Hart, inept but glamorous art teacher stuck in a failing marriage. Sheba’s overall ennui is obvious to both Barbara and Stephen, a ninth grader who attempts to cheer his teacher up via some enthusiastic extra-curricular exertions. Naturally, it ends in tears, and, thrown out by her family, Sheba takes refuge from the tabloids in Barbara’s apartment. The ‘Notes’ of the title are Barbara’s attempts to write a sympathetic account of her friend’s downfall, while inadvertently revealing her own dark obsessions.

Like Humbert and Chappy, Barbara subverts conventions of romantic destiny to her predator/victim narrative. She believes Sheba is “the one”, the special friend she’s been waiting for, even if Sheba doesn’t know it yet.

The bond that I sensed, even at that stage, went far beyond anything that might have been expressed in quotidian chitchat. It was an intuited kinship. An unspoken understanding. Does it sound too dramatic to call it spiritual recognition? Owing to our mutual reserve, I understood that it would take time for us to form a friendship. But when we did, I had no doubt that it would prove to be one of uncommon intimacy and trust – a relationship de chaleur, as the French say.

While Barbara hovers, waiting for the mutual heat to bite, Sheba seeks solace in the arms of Stephen, who feeds her sob stories about an abusive father and a terminally ill mother. His attentions feed into Sheba’s vanity, her remorse (she’s in her early 40s) about her rapidly fading youth, her boredom within her marriage, her struggles to control the other students as part of her job, and she romanticizes the sorry liaison as something that benefits them both.

Heller presents Sheba’s hebephilia as an unforgivable weakness of character, a failing that makes her both vulnerable and dangerous. In order to keep her liaisons with Stephen secret, Sheba makes a pact with the devil (Barbara), but can only postpone, rather than prevent, her downfall. The real monster is Barbara, callously extending the cycle of abuse, but it hardly makes her happy. There are no winners here.

Tampa

What would the viciously astute Barbara make of Celeste, the protagonist of Alissa Nutting’s 2013 satire, if she sauntered into her faculty lounge at the start of the school year? Would she recoil in horror, recognizing a predator more ruthless than even herself, or would she smile her tight smile, sit back, and quietly wait for the fireworks to start?

Attractive, 26 year-old junior high teacher Celeste is a momentous anti-hero, a sex-addicted psychopath who dedicates mind-boggling time and resources to the pursuit of her pubescent prey. Like Humbert, her sexual development was arrested at a certain point, and now fourteen year-old male flesh is all this woman wants. She’s arranged her entire life around the fulfillment of her desires: again, like Humbert, hers is not a crime of opportunity but a meticulously orchestrated campaign. As the novel begins, Celeste is about to embark on her first year in a full time teaching post, giving her unfettered access, for the first time since her own teens, to the boys of her dreams.

The resultant stream-of-consciousness is erotica gone rogue. Celeste can’t stop thinking about sex, imagining it, touching it, tasting it everywhere. Her classroom becomes a private playground: she marks ownership by smearing the furniture with her mucus like some demented snail.

“[I]… performed a small act of voodoo, reaching up my dress to the clear ink pad between my legs, wetting my fingertip, and writing their names upon the desks in the first row, hoping by some magic they’d be conjured directly to those seats, their hormones reading the invisible script their eyes couldn’t see. I played with myself behind the desk until I was sore, the chair moistened, hoping the air had been painted with pheromones that would tell the right pupils everything I wasn’t allowed to verbalize.

Celeste’s lecherous quest to identify, isolate and then seduce an appropriate male student is obsessive – and rapidly becomes exhausting for the reader. Celeste never stops. Unlike the other hebephile protagonists, Celeste knows no shame or remorse. She views sex with a pubescent boy as her undeniable right, and will stop at nothing to achieve the orgasms she feels she deserves. She picks a likely candidate, Jack Patrick, because something about him suggests ‘victim’, and then it’s only a matter of time before he’s encased in her secretions.

Nutting also ensnares the reader, cranking up Celeste’s nymphomania beyond peccadillo or perversion into mental illness – or, because it’s unlikely that this is a disorder that can be cured, pure wickedness. She uses the language and imagery of pornography to persuade us that Jack is enjoying himself equally, living every red-blooded schoolboy’s “hot for teacher” fantasy. But, wearying of her priapism, we can see what Celeste cannot, that poor Jack is disintegrating beneath her lips, pounded by a psychopathic powerplay he doesn’t begin to understand. Despite the horny teen stereotypes embedded in his gender, we shouldn’t forget he is young and fragile. He is as much a statutory rape victim as Dolores or Alice, perhaps even more so because he is preyed upon by the blonde, beautiful, desirable Celeste, the woman no one warned him about, the most insidious monster of all.

These books all caused uproar on publication, with the authors accused of deliberate sensationalism, and their continued presence on library shelves makes a lot of people uncomfortable. Sometimes fiction does that. Yet the effect of these books goes far beyond lewd titillation. They drag a criminal act usually committed in darkness and secrecy out into the daylight and examine what makes it so wrong. They raise important issues about our schizoid attitude to sexuality, our obsession with appearing youthful while forgetting what it’s actually like to be young, our rejection of textured experience in favor of plastic innocence. Most horrifyingly, they put us inside the head of a monster – rendered as a thinking, feeling, very human individual – and ask the chilling question “If you met the wrong nymphet, could this be you?” Read them with care.

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .