LURID: vivid in shocking detail; sensational, horrible in savagery or violence, or, a guide to the merits of the kind of Bad Books you never want your co-workers to know you're reading.

Until Monday, when it was removed by the City of Dallas, a white ‘X’ painted on the tarmac marked the spot in Dealey Plaza where, fifty years ago today, an audacious bullet shattered President John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s skull and spattered blood and brain matter across the First Lady’s bright pink suit. The white-hot collision of metal and bone sent seismic waves rippling outwards into culture, politics and art: half a century later we still ride the aftershocks, as the hundreds of anniversary tributes mushrooming across the world’s media this week attest.

This X shows where history stuttered and fiction surged into the vacuum, offering more satisfying exposition than the spindly, weak-chinned, thinning-haired truth. This X fixes the origin of a thousand lurid stories, spiraling between incontrovertible fact and fantastical reconstruction. This X represents mid-point reversal, when the narrative takes a dramatic left turn and audience expectations are overthrown.

This X indicates the beginning – or the middle or the end – of the ultimate ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’. Proceed hence in any direction, north, south, east, west, or back, and to the left.

And what an adventure it is, drawing on classic myths and legends, historical precedents and, perhaps, alchemical rituals. Circumstances on and leading up to 11/22/63 are often referred to in terms of Arthurian epic – “Don’t ever let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was Camelot” – with JFK presented as the bright and shining Lionheart, cut down in his prime.

According to Jackie, JFK “devoured” stories of the Knights of the Round Table as a boy. As a grown man on the campaign trail in 1960 he identified with Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, a reworking of the myths surrounding Theseus. Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s definitive book A Thousand Days: Kennedy in the White House describes the (actually, 1036 day) Kennedy presidency in terms of “the life-affirming, life-enhancing zest, the brilliance, the wit, the cool commitment, the steady purpose.” British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan was impressed by the way the Kennedys held court at the White House, the

According to Jackie, JFK “devoured” stories of the Knights of the Round Table as a boy. As a grown man on the campaign trail in 1960 he identified with Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, a reworking of the myths surrounding Theseus. Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s definitive book A Thousand Days: Kennedy in the White House describes the (actually, 1036 day) Kennedy presidency in terms of “the life-affirming, life-enhancing zest, the brilliance, the wit, the cool commitment, the steady purpose.” British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan was impressed by the way the Kennedys held court at the White House, the

casual sort of grandeur about their evenings, always at the end of the day’s business, the promise of parties, and pretty women, and music and beautiful clothes, and champagne, and all that. I must say there is something very 18th century about your new young man, an aristocratic touch.

This subtle elevation of elected politician to the status of symbolic king is part of the reason behind our enduring fascination with his murder. The familiar chronicle of events references tales of heroes and villains of yore, but transposes them to 20th Century America. Within this context, the assassination becomes regicide, an act that harks back to the earliest days of civilization as a fast-moving game of thrones, and is part of our storytelling DNA.

Hereditary monarchs have ruled since records began, some more effectively than others. Regicide was once the only way of removing an unfit leader’s hands from the rei(g)ns, and could be framed as an honorable, even pious act. Warrior kings determined succession on the battlefield with the divinely sanctioned swipe of a sword. The royal assassin could be next in line for the job, or a title and a nice piece of land bestowed with gratitude by the new incumbent. Regicide has always been an easy way for a nonentity to make a reputation.

Despite belief in the Divine Right of Kings, or in the charismatic healing powers that came with ascension to the throne, monarchs across early modern Europe were at much greater risk of homicide than any other sector of the population. A recent study puts the violent death rates of monarchs reigning between 600-1800 at about 1,002.6 per 100,000 (as compared to, say, the rate for young black males in the 1990s – the highest risk group in the US – of around 120 per 100,000, or contemporary European rates of 0.6–1.5 per 100,000).[1] Heavy indeed the head...

...for within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps Death his court, and there the antic sits

Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp

– Richard II

The English and French Revolutions were rooted in regicide: Charles I and Louis XVI had to be executed to make way for the new social order. The American Revolution too, therefore, took some of its republican zeal from the principle of regicide and the overthrow of hereditary rule. Paradoxically however, the new-minted office of US President was shaped in accordance with some of the European ideals of kingship, albeit stripped of religious overtones. The Founding Fathers (chiefly Alexander Hamilton) felt that the executive leader should embody “royal dignity”, i.e. he should rise above the common order in terms of possessing authority, morality, stability and that very modern political quality, charisma, providing a stately counterbalance to the ignoble infighting of other elected representatives[2]. In short, the elected President should be a kingly figurehead for the people to look up to, to admire as he conducted ceremonies, to cheer on as he rode at the head of a procession – or a motorcade

John Fitzgerald Kennedy could have been created as a fictional character specifically to fit this narrative of elected presidents-royal. He was born into a family whose wealth and success was emblematic of the ease with which lucky potentates could rise within the United States of America – his great-grandparents were humble Irish immigrants, descended from the Ceannaideach (Gaelic for “grim-headed). JFK was given every advantage of a young prince – education at Princeton, Harvard and Stanford, tours of Europe, a diplomatic post at the Court of St. James, publication of his college thesis (the bestseller Why England Slept), decorated service in the US Navy during World War Two. After his older brother, Joe Jr., was killed in action in 1944, JFK spearheaded his father’s claim to the throne. A latter-day Henry V, JFK’s ascension was just a few elections away (with votes guaranteed by Joe Sr.’s enthusiastic sponsorship of various organizations). However, this yearning for kingship came at a price: not all subjects are equally devoted.

Once the king is on his throne he becomes a target – or a sacrifice. Given the demigod status of kings, killing one can be viewed as a metaphysical act, triggering a powerful release of magical energy. Regicide is as deeply symbolic as it is politically pragmatic (see: Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, Macbeth). In his essay, King-Kill/33: Masonic Symbolism in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, James Shelby Downard suggests JFK was slaughtered as part of a Masonic alchemical ritual, the ‘Killing of the King’. Whether by accident or design, the facts can easily be shaped to fit the sacrament.

Once the king is on his throne he becomes a target – or a sacrifice. Given the demigod status of kings, killing one can be viewed as a metaphysical act, triggering a powerful release of magical energy. Regicide is as deeply symbolic as it is politically pragmatic (see: Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, Macbeth). In his essay, King-Kill/33: Masonic Symbolism in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, James Shelby Downard suggests JFK was slaughtered as part of a Masonic alchemical ritual, the ‘Killing of the King’. Whether by accident or design, the facts can easily be shaped to fit the sacrament.

The date has great significance. In numerology, 11 and 22 are ‘master numbers’, and combine to create the highest master number: 11 + 22 = 33. The location is vital too. Dealey Plaza is located approximately ten miles south of the 33rd degree of north parallel latitude. It was the site of the first Masonic Temple in Dallas, and forms a triangle between the Trinity River and the Triple Underpass, a symbolically appropriate 33-themed killing field. Then there are the “three hoboes” of assassination lore, arrested by the rail tracks behind Dealey Plaza and then released – one of whom may or may not have been Woody Harrelson’s father, Charles, another E. Howard Hunt, one of Nixon’s infamous plumbers – who represent Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum, the three ‘unworthy craftsmen’ of legend, "that will not be blamed for nothing” (echoing the chalk scrawl on the wall above Jack The Ripper’s fourth victim, Catherine Eddowes).

The purpose of the ritual slaughter of the Sun King remains shadowy for non-initiates. This particular 'Killing of The King' was meant either to pave the way for 33rd degree Masons to land on the moon, or to destroy idealism and hope and usher in a new age of fear so that the Illuminati would find it easier to impose their One World Order, or as the second stage in a wave of ‘matter-changing’ reactions begun with the detonation of the first atomic bomb (at another Trinity site, White Sands, New Mexico, also on the 33rd degree of north parallel latitude). It all depends on which link you click.

The deep mythic structure of the assassination has made it fertile territory for all stripes of storytellers ever since the first shot rang out. From eyewitnesses (like Roger Craig, Beverly Oliver and Jean Hill) who rode a wave of notoriety, to participants (like Secret Service Agents Rufus W. Youngblood and George Hickey), to historians (like William Manchester, whose 1967 tome The Death of A President was the first in-depth examination of the case), to the Warren Commission (who produced a 26-volume report) to conspiracists too numerous to mention, to novelists (Loren Singer, Don DeLillo, Richard Condon, Richard North Patterson, James Ellroy and Stephen King) to journalists (Mark Lane, Norman Mailer et al) to film-makers (David Miller, William Richert, Alan Pakula, Oliver Stone) to musical theater (Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins) to contemporary pundits and politicians (John Kerry and Jesse Ventura), it seems everyone has had a go at telling the story their way.

Choose your own adventure: pro or anti-Castro factions? A Mafia hit? The CIA? The KGB? The MIC? J. Edgar smirking in a dress? George Hickey misfiring his Secret Service issue gun? Aristotle Onassis exacting revenge on Joe Sr.? Evil alien lizard kings? A lone nut with a mail-order rifle? It all depends on which link you click. Before the petri dish of the internet, adventure could be found in an nth generation photocopy of The Gemstone File or the handwritten notes in the margins of the local library’s copy of Rush To Judgment or late-night screenings of Executive Action or The Parallax View. Now, it’s an online search term that returns millions of hits, all guaranteed to send you tumbling down the rabbit hole after characters and tropes worn smooth with handling, bald descriptors capitalized as proper names – the Grassy Knoll, the Umbrella Man, Badgeman, the Triple Underpass, the Three Tramps, the Babushka Lady, the Zapruder Film, the Magic Bullet, the Moorman Polaroid. The King is dead! Long live the tales of his demise!

But what of the regicides, the killer(s) of the king, the actors who share the name of the act? Even though history is written by the victors, the regicide often gets short shrift after the deed is done, relegated to the shadows, subsequent status unknown. If they’re not one and the same man, the relationship between the new incumbent and the regicide can be… awkward. At the end of Richard II, Bolingbroke (newly crowned Henry IV) doesn’t seem very appreciative when confronted by a coffin containing Richard II (“though I did wish him dead”) and banishes the assassin, Exton:

With Cain go wander through shades of night,

And never show thy head by day nor light.

The relationship between regicides and the next transition of power can be even more awkward. The 59 named regicides of Charles I (the Commission members who signed the document ordering his execution) lived as men of grace and favor during the Interregnum, but with Restoration in 1660, they were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered (even the ones who were already dead – moldering corpses were exhumed so the punishment could take place).

The relationship between regicides and the next transition of power can be even more awkward. The 59 named regicides of Charles I (the Commission members who signed the document ordering his execution) lived as men of grace and favor during the Interregnum, but with Restoration in 1660, they were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered (even the ones who were already dead – moldering corpses were exhumed so the punishment could take place).

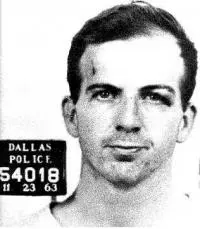

To be a regicide is to be a pivot of history one moment, a discredited fugitive the next. While men who would be king are relatively commonplace, men who would kill kings are a rarer breed. It takes a unique blend of defiance, dissatisfaction, delusions of grandeur and deadly intent to wield the blade (or pull the trigger), knowing that you’re not just taking a human life but effecting a change of regime. In some ways the regicide must be the mythic equal of the target, a shapeshifter or trickster god, powerful enough to destroy the equilibrium of a sitting monarch — at least in their own mind. By the nature of their deed-identity, we expect them to inspire fear and awe. Which is why Lee Harvey Oswald, on first appearance, proved such a disappointment to so many.

...if you put the murdered President of the United States on one side of a scale and that wretched waif Oswald on the other side, it doesn't balance. You want to add something weightier to Oswald. It would invest the President's death with meaning, endowing him with martyrdom. He would have died for something… A conspiracy would, of course, do the job nicely.

— William Manchester

The “wretched waif” presents one of the greatest enigmas of the 20th century. Silenced before he could tell his version of history, he is forever suspected, never convicted. The commemorative metal plaque on the side of the former School Book Depository says it is the site where Lee Harvey Oswald "allegedly shot" JFK. Initially, he was just a pro-Castro nut with a grudge and a gun. A featherweight. Unworthy. But as history unfurled around him, Oswald grew heavier and heavier. His sojourn in the USSR, his powerful friends, his potshot at Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker in April ‘63, his claim “I’m just a patsy”, another fatal shot, this time from Jack Ruby’s gun, all added substance to his crime.

Over time, writers have taken it upon themselves to add substance to his character. Don DeLillo’s 1988 novel, Libra, does a masterful job of filling in the gaps, positioning Oswald as one who (in the words of Marina’s friend, Ruth Paine) “lives in this fantasy about being a great man” but struggles to find a path. Libra follows the fortunes of Oswald from his underprivileged childhood, subject to the mental vagaries of single mother Marguerite, unable to live up to his brothers, through his adolescence spent grasping for political truths despite dyslexia obfuscating the printed word, through his defection to and return from the USSR, still searching for a niche, a job, a sacrifice that would make him special. He didn’t keep an ordinary journal: he titled his personal scribblings ‘Historic Diary’. He’s “the boy with the odd past and out-of-place manner”, a sympathetic, doomed individual. In DeLillo’s version of the story, Oswald is also the victim of regicide, the idealistic youth who falls prey to Agency renegades looking for a patsy to make “history with a fucking flourish”. Along with non-fiction like Norman Mailer’s exhaustive tome Oswald’s Tale: An American Mystery (1995), and Priscilla Johnson McMillan’s 1977 book, Marina And Lee (an account of Oswald’s life in Minsk and thereafter, based on conversations with his wife), Libra builds a picture of Oswald’s deeply flawed humanity, a man with at least some weight and agency, more than just a flimsy cog in a conspiratorial machine.

But still, it seems, Oswald doesn’t carry enough weight to be believable as a lone regicide. A Gallup poll conducted earlier this month suggests 61% of Americans think he was part of a conspiracy[3]. While this is the lowest percentage in almost 50 years (the peak of 81% came in paranoid 1976), it still represents a significant majority. James Ellroy’s 1995 novel American Tabloid embraces this perspective and rewards the reader with regicides weighty enough to earn the name, a triumvirate of career troublemakers, Pete Bondurant, Kemper Boyd and Ward Littell. They’re men’s men, whip-smart, ruthless, quick on their feet both literally and figuratively whether they’re tangling with Mafia goons, pro-Castro drug-runners, or the local Klan.

American Tabloid follows their adventures from November 22, 1958 to November 22, 1963, on the inside and outside of various clandestine activities, some bankrolled by the Mob, others by government agencies, yet others by funding from both sources. Ellroy tells the story as pulp fiction meets scuttlebutt, playing up the sordid real-life details of JFK’s womanizing (“Jack went through his little black book and sideswiped a hundred women inside six months”), Joe Sr.’s Mob buddies and vote-buying, RFK’s obsession with organized crime, and the CIA’s narcotics exploits to fit his salacious narrative frame. Ellroy presents the assassination as the result of a conflict of interest between anti-Castro Cubans, rogue elements in the CIA and FBI, and the Mafia, with the flames fanned by J. Edgar Hoover, Howard Hughes, and Jimmy Hoffa, plus a supporting cast of hundreds of disgruntled operatives – all ably coordinated by Kemper, Boyd and Littell. This creates a massive counterweight for the doomed king. JFK is up against secret, all-tentacled forces that are practically invincible. Regicide isn’t about pitting one man against another, it’s just a matter of time. With Ellroy’s mix of testosterone, financial interests, political in-fighting, paranoia, surveillance, counter-surveillance, and plain old rage and hate, it’s inevitable that something will blow — the President’s brain through the top of his skull.

Other novelists set aside the hard historical truths and play fast and loose with the circumstances, defying the concept that the king must die, or even that a regicide has to be important within the story. They reduce Oswald, or write him out, denying him the attention he so desperately sought. In 11/22/63 (2012), Oswald is a supporting character, observed from a distance, a distraction to the unfolding love story that drives the A-plot. Stephen King's time-traveler protagonist, high school English teacher Jake Epping, spends a lot of time in the house opposite the Oswalds’ on Mercedes Street in Dallas, spying on the ongoing domestic discord between Lee and Marina, and wondering if he – like Oswald – is presumptuous enough to try to change history by removing a piece from the game. Really, though, he'd rather be with Sadie, a much weightier individual in every way. In Idlewild (1995), Mark Lawson constructs a might-have-been version of America where JFK survived Oswald – long enough to lose his looks and nurse regrets. D.M. Thomas’s Flying Into Love (1992), places the assassination in a dreamscape, as Jackie and two nuns (one who hates the Kennedy mystique, masturbating to the Zapruder film, and one adoring fan) weave an alternative reality through fantasy and projection — again diminishing Oswald. In The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) J.G. Ballard utilizes the assassination as a driving force behind his characters’ neuroses, and ends with “The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race” – with Oswald on hand merely to fire the starting pistol.

The Dealey Plaza X, therefore, marks a spot more theoretical than tangible, where a magic bullet began more than it ended. Fifty years on, the slew of stories about the who/what/why of 11/22/63 shows no sign of ceasing, although, increasingly, people seem to prefer the versions where Oswald acted alone. These days, unfortunately, we get Oswald. We understand why he'd want to pull the trigger and catapult himself into history in ways our parents and grandparents didn't. Perhaps the X identifies the point where we began our journey towards becoming a nation where regicidal inclinations are the rule, rather than the shocking exception? In our society, partly thanks to Oswald's shadow, it's easier to conceive of killing a king than being one. Today we would have no problem accepting the explanation that some messed-up kid, off his meds, with a miserable home life, caused such carnage. The ‘Lone Nut With A Gun’ has become a symbol more American than apple pie. In 2013, it seems there are Lee Harvey Oswalds — angry young men, depressed, unfulfilled and aggrieved, blaming an unheeding administrative elite for their ills — lurking on every Elm Street. Amid the solemn remembrances of today, amid the discussion about who owns this story and who tells it best, we should be only too aware that those who don't learn from the past are condemned to repeat it.

What's your favorite book connected to the JFK assassination, fiction or non-fiction?

[1] http://bjc.oxfordjournals.org/content/51/3/556.full

[2] American Kingship? Monarchical Origins of Modern Presidentialism by William E. Scheuerman Polity Vol 37, Jan 2005

[3] http://www.gallup.com/poll/165893/majority-believe-jfk-killed-conspiracy.aspx

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .