LURID: vivid in shocking detail; sensational, horrible in savagery or violence, or, a guide to the merits of the kind of Bad Books you never want your co-workers to know you're reading.

…the hundred-carat headline, running fast and loud on the early morning freeway, low in the saddle, nobody smiles, jamming crazy through traffic and ninety miles an hour down the center stripe, missing by inches… like Genghis Khan on an iron horse, a monster steed with a fiery anus, flat out through the eye of a beer can and up your daughter’s leg with no quarter asked and none given; show the squares some class, give em a whiff of those kicks they’ll never know… Ah, these righteous dudes…

– Hunter S. Thompson, Hell's Angels: The Strange And Terrible Saga of The Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs

The Sons of Anarchy Motorcycle Club, Redwood Original thunder back onto our television screens this week, gunning helter-skelter towards the conclusion of their adventures. Inevitably, these final episodes will be bloody and tragic. Kurt Sutter’s epic re-imagining of Hamlet has snaked its way through six twisted seasons, and the seventh promises to bring more of the same: murder, drugs, guns, rats, rivalries, feds, a succession crisis, broken hearts and retribution for crimes long past.

Sons of Anarchy wears its Hamlet influences on its cut (Clay/Claudius, Jax/Hamlet, Gemma/Gertrude, Tara/Ophelia). Yet the key characters — for all their historical precedents — are contemporary. At the center of their drama lies an outlaw motorcycle gang, a modern manifestation of ancient traditions of brotherhood, and a peculiarly American — albeit one that has chapters worldwide.

The members are road warriors, mounted on powerful steeds elevating them beyond the blue-collar grind that might otherwise be their lot. They’ve earned the right to wear club colors, to cast a vote in club decisions, and to rely on the steadfast loyalty of their club brothers. Every last one is an anti-hero; conflicted, flawed, often a convicted criminal, but nonetheless guided by strict behavioral protocols and a rock-solid honor code. The club, and the club’s interests come first, last and always, above the law of the land, above family ties, above individual survival instincts. Shakespeare isn’t the only inspiration, Arthurian legend and Alexandre Dumas also reverberate: “All for one and one for all."

This fearless brotherhood of motorcyclists offers a seductive paradigm for the rest of us, traveling our roads in air-conditioned silver boxes without the wind on our face or the roar of a Twin Cam 96 engine in our ears. Motorcycle gangs represent a unique brand of freedom and lawlessness, one wrapped in a strict dress code and subject to a rigid hierarchical structure. From the modifications riders make to their machines to brutal hazing rituals for Prospects to the arcane patch system that shows the depths members have plumbed for their club to the Nazi regalia to the dire personal hygiene, much of biker culture is dedicated to signaling “DANGER!” and keeping outsiders out — and to living up to their own worst press.

From The Wild One to Sons of Anarchy, the public image of motorcycle clubs is part fact, part lurid fiction. From easy riding and zen maintenance tips to salacious headlines and exploitation flicks, via various tell-all memoirs from undercover ATF agents and the latest addition to the oeuvre, biker erotica, we love MC stories, the bad-asser, the better. We don’t want to know about the vast majority of weekend warriors, law-abiding citizens who labor in banks, corporate HQs, schools and hospitals in order to fund their expensive motorcycling hobby, and who ride together at weekends to raise money for charity and support their local communities. We’re fixated on the minority of desperadoes who perpetuate the myths.

These Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, the focus of all the attention, are known as the One-Percenters, after an oft-repeated but possibly apocryphal comment attributed to the American Motorcycle Association, about the minute proportion spoiling the reputations of the other 99%.

Getting Ready To Rumble

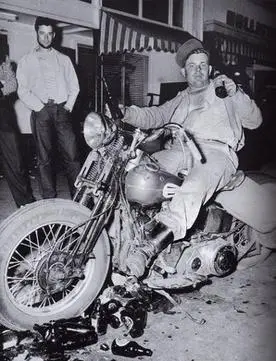

That remark came in the wake of Life magazine’s coverage of the biker bad behavior in Hollister, California, over the 4th of July holiday weekend in 1947. The town had hosted annual ‘Gypsy Tour’ motorcycle races during the 1930s, and, with the war well and truly over, it looked forward to getting its lucrative fundraising event back on track.

Unfortunately, the good burghers of Hollister (population: 4,500) hadn’t taken into account the transformation wrought by the war in motorcycle clubs. Many servicemen got their first taste of two wheels courtesy of the Harley-Davidson WLA, a specially adapted military bike with blackout lights, a scabbard for a Thompson submachine gun, plus fenders and crankcase redesigned for navigating extremely muddy or waterlogged terrain (the bikes could travel through 16 inches of water without flooding). The U.S. Army used these for reconnaissance and dispatch, utilizing them to go where heavier armored vehicles could not – and they always had more bikes than tanks.

Motorcycle missions tended to be solo, dirty and dangerous, deep into the darkness behind enemy lines. The dispatch-rider was a vulnerable moving target, with few defenses other than speed, agility and bravado — and a willingness to risk entanglement with barbed wired (see: Steve McQueen at the end of The Great Escape). Bikes attracted, and perhaps even created, a specific type of soldier, the adrenalin junkie. When the war was over these men couldn’t relinquish their need for speed, and availed themselves of cut-price WLAs that, now surplus to military requirements, were flooding the domestic market.

These men also flooded into existing motorcycle clubs, searching for the camaraderie and thrills of their service days. For thousands of men, reintegration into civilian life was not an option, and they sought action, identity and sanctuary in their local chapter. The clubs offered a uniform, hierarchy, male companionship and, often, a free-flowing supply of alcohol or drugs to dull the pain. The Boozefighters, founded in 1946 by the legendary "Wino" Willie Forkner, dubbed themselves “a drinking club with a motorcycle problem”. For traumatized veterans who had broken all family ties, what wasn’t to love?

So, the riders who roared into Hollister on their souped-up WLAs on 7/4/47 were a different breed to their genteel pre-war compadres. 4000 of them descended, mainly from California, but also from clubs as far away as Florida. The ensuing chaos was down to numbers: there weren’t enough beds or restrooms for everyone, so the visitors improvised, sleeping off the vast quantities of beer consumed in haystacks, on sidewalks and lawns, and urinating where they stood. There weren’t enough races to occupy them all, either, so they created their own entertainment with informal drag runs up and down the streets, riding bikes in and out of bars, and water balloon fights. Those on the front lines (bartenders and local cops — all seven of them) had a tough weekend, but other eyewitnesses claimed it was no big deal. The only damage done by the bikers was to other bikers, and all they left behind were thousands of empty beer bottles. 150 individuals were arrested, mainly for public drunkenness, and given fines ranging from $25 to $250 in a specially convened court session. The severest penalty was handed out to one “Jim Morrison, 19, of Los Angeles”, who earned himself 90 days in the slammer for indecent exposure. Compare that to the destruction left in the wake of your average cleancut college kid spring breaker in 2014…

The only things running truly amok were the headlines in the San Francisco Chronicle over the following days: “HAVOK IN HOLLISTER — Motorcyclists Take Over Town, Many Injured”; “MORE ON HOLLISTER'S BAD TIME — 2000 'Gypsycycles' Chug Out Of Town And The Natives Sigh 'Never Again'", adding more details, for readers’ delight, on the "worst 40 hours in Hollister history". The story was picked up nationally, and Life magazine ran a brief account under a full-page moral panic-inducing photograph.

"Hollister riot life magazine 1947" licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia.

The veracity of the image has been called into doubt. The man standing in the background, Hollister projectionist Gus Deserpa, claimed he watched as the beer bottles were arranged carefully around the motorcycle, and a passing drunk asked to pose, a claim vigorously denied by the Chronicle’s editor. Whether the photo was staged or genuine, it introduced a new boogeyman to a generation of Americans. The American Motorcycle Association was provoked into its fiat regarding the “one-percenters” — a label quickly adopted as a badge of pride by the outlaws themselves — and a cultural phenomenon was born.

“Whaddaya Got?”

We’re the one percenters, man — the one percent that don’t fit and don’t care. So don’t talk to me about your doctor bills and your traffic warrants — I mean you get your woman and your bike and your banjo and I mean you’re on your way. We’ve punched our way out of a hundred rumbles, stayed alive with our boots and our fists. We’re royalty among motorcycle outlaws, baby.

– A Hells Angel speaking for the record, Hell’s Angels: The Strange And Terrible Saga of The Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs

The events in Hollister inspired a short story by Frank Rooney, "Cyclists’ Raid", which appeared in the January 1951 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

Tragedy unfolds from the perspective of small-town hotelier Joel Bleeker. His hackles rise the moment ‘Troop B of the Angeleno Motorcycle Club’ rumbles up the main street “with the noise of a multitude of pistons and the crackling of exhaust pipes.” They strike him as militaristic and un-American:

The whole flanking action, singularly neat and quite like the various vehicular formations he remembered in the Army, was distasteful to Bleeker. It recalled a little too readily his tenure as a lieutenant colonel overseas in England, France, and finally Germany.

Although the leader of the gang, Gar Simpson, is calm, courteous, and in control of his men, insists on paying for use of the washrooms, and invites Bleeker for a drink, the hotelier can’t shake off a feeling of dread, which is further stoked by his guest’s refusal to remove

his flat green goggles, an accouterment giving him and the men in his troop the appearance of some tropical tribe with enormous semi-precious eyes, lidless and immovable.

The raiding Cyclists straddle the line between the previous decade’s demons, Nazi fiends, and the bug-eyed alien mutant swamp things that would dominate the coming wave of horror. They have an ‘Other’ quality wholly of the era: they look like Americans, talk like Americans, but underneath their goggles they subscribe to a warped value system, raising an instant red flag. Bleeker’s unease is justified as the rebel motorcycle club wreak havoc, Hollister-style. Rooney imbues his fiction with much more sinister undertones, however, and his cyclists leave much worse than broken beer bottles in their wake.

Indignant, outrageous, titillating, feeding directly into zeitgeist anxieties, Rooney’s short story was perfect fodder for Hollywood, fact generating fiction generating B-movie melodrama. "Cyclists Raid" was adapted into The Wild One, a star vehicle for the fast-rising Marlon Brando, who cemented his smoldering reputation as Johnny Strabler, leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. Billed as “the story of a gang of hot-riding hot-heads who ride into, terrorize and take over a small-town” (alternate tagline: “"Hot feelings hit terrifying heights in a story that really boils over!"), The Wild One aimed its sermonizing straight at the emerging youth market and rode waves of audience-grabbing controversy from the outset. The original screenplay was rejected by the MPAA/PCA as “a story of violence and lawlessness to such a degree (that it is)... anti-social”, and the film was banned in the UK for the next fourteen years.

The clash between hepcat slang-slingers and inept oldsters now seems almost comically dated, (daddio!) but The Wild One’s poster boy remains an icon of cool. Brooding, sideburned, Perfecto- jacket-wearing Marlon Brando atop his very own Triumph Thunderbird 6T motorcycle, spawned a host of imitators (including James Dean), landed on the ‘Who’s Who of the Counter-Culture’ sleeve of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and imbued the maverick figure of the outlaw biker with undeniable sex appeal.

“Blood, booze and semen-flecked”

Where Brando led, the Beat Generation followed. As the 1950s grumbled onwards a new wave of vets from the Korean War swelled the gang ranks, alongside other disaffected young dropouts. Beatniks admired the bikers’ middle fingered salute to authority, envied their freewheeling, often nomadic lifestyle, and were eager to share their steady supply of illicit drugs. More and more Chapters sprang up in small towns and cities across California, some of them adopting existing colors, others creating their own. In Oakland, a rebellious teenager named Ralph "Sonny" Barger adopted the World War II air force squadron nickname, “Hells Angels” (sans apostrophe) for his gang, formed in 1957. He wasn’t the first to use the name, or the distinctive red and white death’s head patch, but Sonny and the Oakland Hells Angels would come to dominate the scene.

It was a good time to play maverick kings. Most crime takes place in secret, after dark, but the outlaw motorcycle gangs rode the waves of moral panic generated post-Hollister right up Main Street in the hot light of noon. They roared into small towns en masse, in colorful costumes, riding the noisiest, most distinctive machines they could find, and traded off their generalized reputation for violence and rape. In California, Attorney General Thomas C. Lynch released a report on motorcycle gangs in the state, singling out the Hells Angels as particularly dangerous. Police up and down the state were given special instructions on how to deal with renegade motorcyclists, and, once again, the national media provided salacious coverage of the New American Menace.

A young journalist named Hunter Stockton Thompson was unimpressed by the outlaw mystique exuded by the biker gangs, and cynical about the claims made in the Lynch report. He decided to dig deep for the truth, and spent months riding with various Oakland and San Francisco Hells Angels, drinking at their bars, accompanying them on club runs and tape-recording every boastful rant or confrontation with authority. He gained unprecedented access to a group usually suspicious of journalists and was able to document their day-to-day experiences from the inside. Perhaps the Angels sensed a fellow hell-raiser in their midst? Thompson’s willingness to imbibe large quantities of drugs and alcohol, shoot out windows with his shotgun and wave his press pass at cops while yelling about police harassment endeared him to the gang.

Once the Angels got used to having him around, they opened up to Thompson about their customs and practices. He gleaned crucial insights, such as the source of the “powerful stench” peculiar to bikers. This emanates from the Levi’s jeans and jacket worn to the initiation ceremony, which are then covered in feces and urine during “a solemn baptismal”:

These are his “originals”, to be worn every day until they rot. The Levi’s are dipped in oil, then hung out to dry in the sun – or left under the motorcycle at night to absorb the crankcase drippings. When they become too ragged to be functional, they are worn over other, newer Levi’s …they aren’t discarded until they literally fall apart. The condition of the originals is a sign of status. It takes a year or two before they get ripe enough to make a man feel he has really made the grade.

Their Golden Rule (written into the club charter as Bylaw Number 10) echoes Dumas: “When an Angel punches a non-Angel, all other Angels will participate”. In conversation, Sonny Barger is consistently on message about the Angels as a band of brothers, drawn together by their passion for bikes, and Thompson's inner speed fiend gets it:

…You’ve got to see an outlaw straddle his hog and start jumping on the starter pedal to fully appreciate what it means. It is like seeing a thirsty man find water. His face changes; his whole bearing radiates confidence and authority. He sits there for a moment with the big machine rumbling between his legs, and then he blasts off…

The cool-headed journalist, however, remained cynical. During the course of his research, Thompson could never shake off his innate fear of the Angels, of their love of violence, their insistence on sledgehammer retribution for even the slightest perceived insult, and their entrenched misogyny. This last proved his undoing with the Angels. When Thompson committed the unpardonable sin of asking a full patch member to please stop kicking the shit out of his old lady, four or five Angels stomped him. Thompson fled, driving fifty miles to the ER (“My face looked like it had been jammed into the spokes of a speeding Harley, and the only thing keeping me awake was the spastic pain of a broken rib”), and never went back.

Hell’s Angels: The Strange And Terrible Saga of The Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, was published in 1966. The book made Thompson’s career, establishing him as a leading chronicler of all things counter-culture, and bringing his unique voice to a wide audience for the first time. But his interview subjects did not appreciate being guinea pigs for gonzo journalism, and resented their newfound infamy as “the rottenest motorcycle gang in the whole history of Christendom… pure animals… a human zoo on wheels”. Oblivious to the pleasures of Thompson’s prose, they accused him of exaggeration, fabrication and grievous misrepresentation. They even arranged a showdown on national TV, in front of a studio audience who giggle helplessly at Workman's suggestion that “sometimes, you gotta beat a woman like a rug”:

Undercover Brothers

Where Thompson led, living among the outlaw motorcycle gangsters and infiltrating their secrets with an exposé in mind, others followed. The Lynch report set the stage for Law Enforcement vs. the One-Percenters, and, from the late 1960s onwards, the FBI and ATF took aim at the colors flying from the backs of the Hells Angels, the Mongols, the Outlaws, the Bandidos and the Vagos. They believed their targets were running drugs, guns and girls to fund the outlaw lifestyle, and committing regular murder, rape and assault with various weapons to sustain the requisite miasma of menace. However, with full patch members bound by a code of silence, and witnesses too terrified (or too dead) to testify against the outlaws, evidence was hard to come by.

The only way to incriminate a chapter is to use an undercover agent or confidential informant to bear witness. This entails a brave individual going deep, for several years, working his way up from hang-around to prospect to full patch. To move up the ranks he must convince his newfound brothers he’s too illegit to snitch by running errands, riding a Harley, buying and selling contraband, defending his honor in barroom brawls and generally conducting himself in a manner befitting a wannabe member of a tight-knit criminal fraternity. The stakes on such an operation are high: dirty rats wind up dead.

The agents who survived their ordeal inside biker gangs have some lurid tales to tell. In Befriend and Betray: Infiltrating the Hells Angels, Bandidos and Other Criminal Brotherhoods, Canadian Alex Caine details his many years of cross-border undercover operations from the late 1970s to the early 2000s. A Vietnam veteran and ex-convict, he was recruited by the RCMP because there was no need to fake his background or demeanor. He was the real, renegade deal — with a conscience — the ideal man to wear a wire. Caine compares sting operations against Hong Kong Triads and the Ku Klux Klan with his experiences inside biker gangs, and there’s no doubt who he considers more dangerous.

William McQueen began his career on the other side of the thin blue line. He was a veteran law enforcement agent, bored with routine assignments, who leapt at the opportunity to go deep undercover inside the Mongols. He disappeared into alter-ego, Billy St. John, grew out his beard, fired up the AFT-owned Harley Davidson and started hanging out at notorious Mongol watering-hole, The Place in San Fernando Valley. For the next twenty-eight months he embraced the outlaw lifestyle and affiliations, burrowing deep inside the organization, rising from prospect to full patch to chapter secretary-treasurer at breakneck pace, never more than a heartbeat away from exposure and certain death. He describes his eye-popping experiences in Under And Alone: The True Story of The Undercover Agent Who Infiltrated America’s Most Violent Outlaw Motorcycle Gang.

George Rowe was fed up at the way the Vagos MC were terrorizing the good people of Hemet, CA. Rowe was no angel, a former meth dealer turned landscape gardener, but he was driven by a clear sense of what was okay and what was going too far. The Vagos crossed the line when they murdered his buddy, Dave, for standing up for himself in an MC-related altercation in a pool hall. Rowe exacted his own form of retribution by signing up as a volunteer Confidential Informant. Thanks to previous ATF undercover operations, the Vagos were leery of outsiders, but Rowe’s civilian low-life credentials gained him entry to the club. In Gods of Mischief: My Undercover Vendetta To Take Down The Vagos Outlaw Motorcycle Gang, he lays out his determined takedown, via RICO and other federal indictments, of the Hemet Vagos. Mission completed, Rowe’s reward was a new name, new state, new life, courtesy of the WITSEC program.

While these undercover operatives are faced with terrifying, dark moments during their time embroiled within an OMG, they all agree on one positive: once accepted as a member, the outpouring of full patch, ride-with-him, die-for-him full force brotherly love was totally real, totally unlike anything experienced in Straightsville. The sense of being valued and belonging was seductive, enough to make the lawmen fantasize, albeit fleetingly, about disappearing into their hard-riding, violent, dirty biker self, and, like so many of their new brothers had done before them, leaving the real world behind.

Good Vibrations

If the outlaw fantasy is powerful enough to seduce battle scarred ATF agents, it can certainly generate the dynamic force required to drive erotic fiction. In reality, OMGs don’t have the best reputation where women are concerned, but on the pages of a fast-growing number of entries into the ‘tattooed biker prince’ sub-genre of erotica, they’re establishing a magnetic presence. Part Sons of Anarchy slashfic (there seem to be a lot of hunky Vice Presidents and hot guys named variants of Jack, Jax or Jackson), part reaction to a glut of kitten-rescuing firemen, these throbbing tomes also pander to readers who go gooey inside at the thought of a brooding yet vulnerable Brando-figure packing 95 horses between his black leather clad thighs.

J.R. Ward’s delectable Black Dagger Brotherhood are, effectively, an outlaw motorcycle gang, but, for erotica readers who think vampires are so four years ago, and who prefer their fictional sex to be dirty nasty real, there are a lot of handsome new strangers skulking around town. These bad boys all have their own MC: there’s the Prairie Devils series by Nicole Snow, the Scorpio Stingers from Jani Kay, the Sinners from Bella Jewel, Hell’s Disciples from Jaci J, and the Horsemen and Silver Demons from the queen of them all, Madeline Sheehan. These writers are extremely prolific, and there seems to be an insatiable appetite amongst eReaders for their work. Just look for tattooed manflesh on the front cover and open up your Kindle to full throttle: crazy times for old ladies guaranteed.

Our continued lionization of biker gangs reflects America's twisted love affair with lawlessness. We lock up our daughters when they ride into town and prosecute their criminal activities to the fullest extent permitted by statue. Yet we continue to relish lurid tales of their exploits — Sons Of Anarchy Season 6 averaged 7.3 million viewers. Despite the bad press generated by Altamont, the women raped and nailed to trees, the casino brawls and the ongoing deadly turf wars, the Wild Ones embrace the fictions swirling around them, and represent as essentially romantic figures, riding proud and free. When a phalanx of full patch riders bestride giant hogs roars past on the freeway, we pull over, scrambling for our phones to grab a quick pic. In the thrumming of their engines we hear an echo of our chivalric past, and in that sound a promise that those born to be wild can still head out on the highway. We envy their majesty as the convoy rumbles past, destination debauchery. We give them a moment to haul ass — no one wants to drive too closely in their wake — before puttering onwards, safe, inadequate, but perhaps a little cheered by their continued existence on the outlaw limits.

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .