Does a creation take on a life of its own? When does the artist end and the art begin?

That’s the question that has plagued Star Wars since Disney purchased Lucasfilm in 2012 and immediately started work on continuing the franchise. The result has been 2015’s The Force Awakens, proclaiming itself Episode VII in the opening scroll, and spinoff Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, with many more planned. But are they valid?

George Lucas himself made the original trilogy between the years 1977 and 1983, and the prequel trilogy between 1999 and 2005. He declared the series done, but always dallied with ideas for a sequel trilogy. After all, he claimed in interviews back in the halcyon days that he had originally envisioned a nine- or twelve-part series. And he had written an outline that Disney got in the deal, even if “[m]uch to Lucas’s irritation,” they ended up not using it.

But two recent events put in focus the illegitimacy of continuing a series not just beyond its natural conception, but its original authors’ vision: the release of George Lucas: A Life, his biography, and the death of Carrie Fisher. The former delves into the auteur’s life and how Star Wars came from a personal place. The latter reveals an unexpected controversy surrounding what to do about Leia, whether to write her out, recreate her with CGI or recast.

The question is whether or not a story and a character can legitimately live on beyond the human beings that brought them to life. Although there are always exceptions to the rule, in this instance it’s clear that any Star Wars made without the involvement of George Lucas, and any continuation of Leia’s character beyond Episode VIII, now titled The Last Jedi, without Fisher is fan fiction.

First, some clarification. There’s a great YouTube channel called Folding Ideas, hosted by film critic Dan Olson. Episodes can range from 2 minutes to over a half hour, and in them Olson discusses film theory and applies it to movies across the spectrum, but mostly new releases. In the episode titled “The Thermian Argument” from September 17, 2015, he argues people cite diegetic consistency as justification for poor quality or wrongheaded filmmaking, such as exploitation of rape or gratuitous mass destruction. But the diegesis is anything that happens within a movie, so to argue that so-and-so character had to be raped on Game of Thrones, for instance, misunderstands how storytelling works. A situation only exists, and seems to present limited options for solving a conflict, because the “author” steered it in that direction.

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxV8gAGmbtk]

That brings up the question of who is the author and why does it matter. In movies, collaboration makes it almost impossible to assign credit for the final product. In the case of Star Wars, Lucas wrote and directed it, drawing on childhood inspiration, amongst other life experiences.

"When I was very young, I loved make-believe,” said Lucas. “But it was the kind of make-believe that used all the technological toys I could come by, like model airplanes and cars. I suppose that an extension of that interest led to what later occupied my mind, the Star Wars stories."

But suggestions from friends and mentors, like Francis Ford Coppola, transformed the movie that was eventually released in 1977.

With Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi that collaboration process deepened. ESB had a story by Lucas and a screenplay by Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan, but even then “[[m]uch of the basic structure for what would eventually become Empire was in place in the first treatment”. The same was true of RotJ which had Kasdan return to write the screenplay with Lucas but was directed by Richard Marquand. But there’s no denying Lucas guided where the story was going, vetoing anything that went against his wishes.

But by the 1990s he had taken all three movies and made them his own with the Special Edition tweaks, and cemented his ownership with the prequels. Not only were these movies written and directed by him, with only one co-screenwriter credit for Attack of the Clones, but they retroactively went back and overpowered the budding expanded universe that had been forming. Started first with Lucas’s own brainchild, the novel Splinter of the Mind’s Eye written by Alan Dean Foster in 1978, this EU continued with the Marvel Comics Star Wars series, the Dark Horse Comics, the Bantam novels and much more. But all of this was beholden to the higher authority that was Lucas, ‘who would ultimately decide what was considered “canon” — that is, officially part of the Star Wars universe,”’ with elements such as Boba Fett’s backstory and a truncated time frame evolving as his movies rewrote the history of the galaxy far, far away.

There’s no denying Star Wars had become a monster of a property, but it was a property with a guiding mind and voice. So what happens when the story gets away from the human being that created it?

Take, for instance, Sherlock Holmes. Certainly there have been riffs on the character over the years. There was the Young Sherlock Holmes movie from the ‘80s that imagined Holmes and Watson meeting as children at school. There’s the Sherlock BBC television series starring Beneditch Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman that reimagines the characters in the modern day, as does Elementary, except set in the United States and with Lucy Liu as Watson. And in 2015 there was Mr. Holmes starring Ian McKellen, a movie hypothesizing Holmes’s final days as his memory fades and he attempts to solve his last case. But all of these stories acknowledge they are outside the canon of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original work and are not “real” versions or continuations of the story.

And in the case of Star Wars, the fact that it was created as a movie in its original form, and not as an adaptation of written stories, means it’s completely reliant on the human beings that originated it. They created not just the look and the feel of the series, but imbued the characters with specific takes that are without interpretation. Mark Hamill brought Luke Skywalker to life from scratch, as did Harrison Ford with Han Solo, as did Carrie Fisher with Princess Leia. Which, of course, brings up the question of Carrie Fisher’s recent death and how the Star Wars movies progress from here.

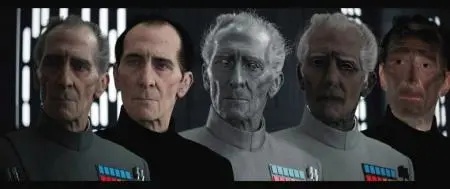

Apparently all of her scenes for The Last Jedi have been filmed, but there was an intention for her to appear in Episode IX. In the wake of Fisher’s passing there has been discussion online about the three routes to take from here: write Leia out of the movie, and franchise, entirely; recast Leia, with such outlandish names as Stevie Nicks or Meryl Streep thrown out; or recreate Leia as a digital skin for another actor to wear. The last idea has precedent, in Hollywood but especially in this very series with the recent Rogue One giving Grand Moff Tarkin an expanded role with an actor “wearing” a digital skin, and a young Princess Leia herself showing up at the end of the movie. Both were done using footage from the original Star Wars.

So how does Star Wars move forward? First of all, here’s some hard and fast rules for recasting.

Pre-existing material like comic books, books, and video games are the base for a character, so any movie is trying to approximate the essence of that character. Therefore, that kind of role can be re-casted mid-series, i.e. Batman Forever replacing Keaton with Kilmer, Iron Man 2 onward replacing Howard with Cheadle.

In the case of something like Mad Max: Fury Road, it’s ambiguous at best if it’s a sequel to the original trilogy. It also came out 30 years after Beyond Thunderdome, allowing for breathing room to distance the association. Time is a necessity.

Although prequels in general are discouraged, if a movie takes place earlier in the chronology of a franchise it’s okay to cast a younger actor. Those actors should always be encouraged to do their own thing, however, and not just an impersonation of the original actor, although that’s probably unavoidable. Alden Ehrenreich has his work cut out for him.

Minor characters can be recast, and have been to the point that barely anyone notices. However, replacing the character with someone similar certainly makes for more diegetic consistency. Take, for instance, Nigel Wolpert in the later Harry Potter movies, who replaced Colin Creevey from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, or B.J. Harrison replacing Tom Hagen in The Godfather Part III.

What it really gets down to is this simple question: why do I like what I like? Reading a book, a character can come to life through their description and dialogue and actions, but in the end it’s the reader’s imagination that does most of the work. Comic books establish a solid visual template, but even then they’re idealized and impossible to recreate, and there is the question of artistic style differences, with Sam Keith’s version of Batman bearing little resemblance to Alex Ross’s. And video games take it a bit further by putting the character into motion and giving them a voice, but there’s still that question of style. People just can’t have hair that big or guns or swords or boobs—it does not translate to live action.

But with movies, the actors are the linchpin. An actor can elevate a bad script, as Harrison Ford famously said of Lucas’s script, “You can type this shit, but you can’t say it.” So in the end a character’s lifeforce is bestowed upon them by the actor. The writer and director supply the material, but the actor shapes it. Therefore, if an actor originated a role, and that actor dies mid-series, just let them die.

And as for CGI, when does it stop? The slippery slope argument is usually just that, a slippery slope, but if recently-dead actors can be brought back, when do Judy Garland and Bogart and Heath Ledger get brought back? Similarly, why ever see an aged Indiana Jones if Harrison Ford can be de-aged?

Because it’s inauthentic and gives into our worst instincts. As Nick tells Gatsby, “You can’t repeat the past.” And you shouldn’t want to, because art can’t move forward if technology literally allows us to replicate what’s been done before. Instead of wanting to further Star Wars like a perpetual motion machine, artists should be worrying about and working on what the next Star Wars will be.

So let Leia die, and preferably let Star Wars die. Although I know that’s not realistic. It’s out of the artist’s hands now, and has become solely a product. But once upon a time an entire universe resided in the head of one man, and a few trusted collaborators teased it out and brought it to life. That method and ideology should be something to strive for, not balk out.

So care about the people. Put your loyalty there, and not to fictional characters and worlds and especially corporations. Characters don’t exist outside of the hands and minds that craft them. They won’t continue to exist without those people. And there won’t be anything new and original building off those characters and worlds without people.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.