I'm not a creative type like you, with your work sneakers and your left-handedness.

—Jack Donaghey

As writers, we can often find ourselves outside the larger social group. Which makes sense. After all, we wordsmiths are, by nature, observers. We're non-conformists. And let's face it: a lot of large social groups suck.

As writers, we can often find ourselves outside the larger social group. Which makes sense. After all, we wordsmiths are, by nature, observers. We're non-conformists. And let's face it: a lot of large social groups suck.

Despite this, stories about "groups"—such as friends, colleagues and classmates, are perennial favorites. Think And Then We Came to the End, The Outsiders, The Commitments, The Great Gatsby, er...Lord of the Flies.

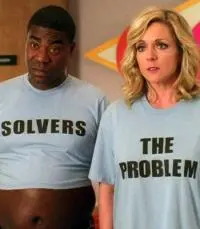

That's why shows such as 30 Rock can be a goldmine of lessons (or "mindgrapes" if you will) on how to portray the ins and outs of group dynamics, as well as their effect on individual characters and the story as a whole.

She texts her gay friends while I write ’til four in the morning eating dry fistfuls of Raisin Bran to stay awake, which, by the way, is how I’m able to ride the fart train to work every day.

—Liz Lemon

30 Rock Mind-Grape #1: Characters can be defined and made likeable (or not) by their interactions with other characters.

The very first episode of the show is a perfect example. When we first meet Liz Lemon, she’s buying all the hot dogs in a vendor’s cart, just to teach the pushy suit who was cutting in line a lesson in justice. (This would have been self-righteous, if she hadn’t then shared the hotdogs with everyone she passed—yum!) Compelled to wrangle obstreperous movie star Tracy Jordan into joining her TV program TGS (“The Girly Show”), she accompanies him to a strip club and even does a (corporate casually clothed) dance on stage. She can hold her own against her obnoxious boss Jack Donaghey when he hurls zingers at her such as, “I like you. You have the boldness of a much younger woman.” By the time the episode is over, we see Liz can get along with people, yet doesn’t take any crap from them, at least not for long. In other words, she’s someone to root for.

As a side note: we also see Liz’s relationship with Pete, the “sane” producer of TGS. Pete is often Liz’s go-to man when it comes to advice on work and romantic relationships. They are close enough that he crashes at her apartment when he’s having marital problems, but the two themselves have a strictly platonic bond. Close friendships between the opposite sex (that don’t result in sex) can be important in defining a primary character. Perhaps someone can come up with an example, but I certainly can’t think of a main character in any medium who had a close friendship with the opposite sex who was not at least somewhat likeable.

I'm going to have to reinvent you—break you down completely and build you up from scratch. Just like Mickey Rourke did to me sexually.

—Jenna

Mind-Grape #2: The progression of your story can be helped as the relationships between characters in the group change and grow.

Case in point: the relationship between TGS stars Jenna Maroni and Tracy Jordan. When they are first compelled to work together, the two attention-grabbing stars resent each other and spend more time thinking up methods of sabotage than learning their lines. However, had this gone on for 7 seasons, it doubtlessly would have become repetitive. Fortunately, Tracy and Jenna realize that being the only actors on the show makes them “superior” to everyone else, and unites their narcissistic personalities in order to beleaguer the rest of the staff and create all sorts of problems only they can solve. Having them evolve from adversaries to allies not only makes two difficult characters more accessible and (sort of) easy to like, it also provides Liz and the other main characters with challenges and situations that move the storyline(s) of the show forward.

The relationship between Jack and Liz is another example. Distaste for each other’s life choices soon evolves into a mentor/mentee relationship between the two. At first, no-nonsense Jack sees Liz as yet another business problem to be solved. However, as their relationship deepens, turning almost into a bromance, Jack finds himself seeking Liz’s counsel and approval just as much. Unlike Liz’s relationship with Pete, there is an element of sexual tension present between her and Jack. However, this is (wisely) sublimated into edgy banter and a more-than-friendly involvement with each other’s love lives. This element of conflict between two characters is useful for keeping readers (and viewers) on their toes.

You know how pissed off I was when US Weekly said that I was on crack? That's racist! I'm not on crack. I'm straight up mentally ill.

—Tracy

Mind-Grape #3: Stereotypes are Blurgh! Unless they're not...

According to conventional TV wisdom, chaotic and neurotic Liz should have thwarted expectation by being a sultry sex goddess when she wasn’t in the office. Jack should have ditched his decidedly un-PC ways of thinking after having his heart melted by the right woman, or an adorable, scruffy orphan with faulty English. Hillbilly Kenneth should have eschewed the Bible-thumpingness with which he was raised and instead walked around quoting Shakespeare or Lao-Tsu. In other words, everyone should have defied expectation, just as we’ve come to expect.

Instead, by being a 24 hour Lemon, Liz allowed us to identify with the vulnerability of a career woman who is questioning whether she can have it all. (Er…do guys ever ask that question?) Jack remained a Reagan-lover until the end, unlike Kenneth, who refused to even vote because choosing was a sin. (At one point, he confessed that he just wrote God’s name on his ballots. “We count those as Republican.” Jack told him.) Observing their extreme views, and how these views affected their interaction with others is a lesson on how to make characters many will have nothing in common with accessible and vital to the plot.

While certain themes have to be handled with care, the fact is: we’re all different, and we all notice. There’s a need for modern-day characters that allow us to objectively explore the major issues of the day: race, class, gender, politics and why New York City is the best place in the entire galaxy.

Hey, Liz. We're playing ‘The Today Show’ drinking game. You do a shot every time they give a dumb travel tip.

—Frank

Mind-Grape #4 I'm Down with the In Crowd—The Benefits (and fun!) of Using Inside Jokes, Quirks and Running Gags.

Unless your schtick is writing the most tragic of Elizabethan dramas, then at some point your characters should have a little fun, preferably with each other. It’s a treat for the reader to see something akin to Liz and her writing staff’s ‘five minute dance parties’ or catch the caption written on one of Frank’s trucker hats. (“Teenage Grandpa” “First-Time Flosser” “Smells”) Then there’s Jack’s ridiculous management-speak, Liz’s ‘yo mama’ jokes and Jenna’s repeated and usually futile attempts to use her “sexuality” to gain an advantage in everything from her career to a table at a crowded chain restaurant. It’s little quirks that help make your work so endearing, readers will want, to quote Tracy, to “take it behind the middle school and get it pregnant.”

That is actually my thoughtful window staring place. Visitors can go over there.

—Jack

![]() Mind-Grape #5: All By Myself: When—and How—to move your character away from the group.

Mind-Grape #5: All By Myself: When—and How—to move your character away from the group.

Just like in real-life, there are times when your characters are going to need to break away from their crowd. A recurrent theme throughout 30 Rock is Liz’s struggle to find a romantic partner and much of her dating life took place away from the comfort of her office. (Of course, if you were dating Dennis Duffy, the Beeper King, you’d probably try to keep it on the DL too.) When Jack was forced out of his executive position, the show saw him venture to DC alone, to brave a world of political incompetence and lack of office supplies. Even when a piece is strongly ensemble-driven, pulling primary characters out to do their own thing keeps everyone from getting stale and allows both the character and the storyline to develop on another level.

From now on, you write and shoot the entire season in two weeks, like Wheel of Fortune or Fox News.

—Jack

Creating a realistic group dynamic can be a challenging task for a writer, but a worthwhile one. Inviting your readers to join an inner circle of your own creation is like asking them to a party where they are sure to be entertained, enlightened and might just give them insight into their own relationships, both on and off the page.

About the author

Naturi is the author of How to Die in Paris: A Memoir (2011, Seal Press/Perseus Books) She's published fiction, non-fiction and poetry in magazines such as Barrow St. and Children, Churches and Daddies. At Sherri Rosen Publicity Int'l, she works as an editor and book doctor. Originally from NYC, she now lives in a village in England which appears to have more sheep than people. This will make starting a book club slightly challenging.

Mind-Grape #5: All By Myself: When—and How—to move your character away from the group.

Mind-Grape #5: All By Myself: When—and How—to move your character away from the group.