No, I did not intentionally do this close to Christmas to make a point. Pinky promise.

I firmly believe that the idea of evolution is so contentious because the concept seems simpler than it actually is. Don't get me wrong, evolution has a beautiful simplicity to it, but it's not intuitive, and it requires some practice before it clicks. Evolution is basically a Bob Ross painting. You see the result, and you think, "I get it, sure," but when you actually put paint to paper, you end up with some artistic abomination that can only be killed with a wooden stake.

I want to use this article to address the common misconceptions about evolution, and hopefully help everybody, regardless of your personal beliefs, to see how this process actually works. If you want to write about evolution and haven't taken a college-level class in evolutionary biology, I would highly recommend you look through this article and make sure you've got it straight.

Disclaimer: As I often do with these articles, I sometimes play a little loose with the terminology to keep things simple. Evolutionary biologists would flay me for saying that we evolved from "monkeys" when in truth we evolved parallel to apes from a common ape-like ancestor. I'm trying to get this concept to *click* for you rather than give you the ability to write a dissertation, but realize that if you are working heavily with evolutionary themes and need specifics, hit the library.

Evolution in the tiniest freaking shell I can find

When a organism (animal, plant, bacteria, etc.) breeds, it passes its genes down to its children. These genes make up how the organism looks and operates. Because dead organisms can't reproduce, the genes that continue in the population are the ones that make the best survivors, since only survivors reproduce. In a stable, unchanging environment, this would eventually lead to a creature that has the best genes for its environment, but because no environment is 100% stable, organisms are in a constant state of adaptation to their environment, and thus are always evolving.

One of the best examples out in nature is that of the peppered moth. Originally, this moth was light gray, which acted as good camouflage in a forest that was covered in light gray trees. There were other variations of the peppered moth out there, including one with a black coloring, but because black is a bad color for camouflaging against light gray trees, these moths tended to be eaten more easily. Moths that are eaten can't pass their genes on, so most of the moths that survived and had children were light gray. Here's a picture of two peppered moths with different paint jobs:

Then came along filthy humans with our factories, and we covered the forest in soot. Light gray trees suddenly got much darker in color, and the light gray moths became much more visible to predators. But guess who was now perfectly camouflaged? The black moths were now harder to see, and thus had an easier time surviving and having babies. More black moths were produced, and eventually the light moths became as rare as the dark moths used to be. Today, environmental air standards have been enacted, allowing the forests to return to their original light gray color, and the light gray moth is making a comeback. It's simple cause and effect.

Notice that no individual moth changed color in response to the environmental changes. A black moth would always be a black moth. Rather, the change came gradually over generations based on which animals could live long enough to breed. The peppered moth population evolved into different colors based on what produced a creature best suited for the environment.

Speciation

Speciation occurs when a single species of organisms, for whatever reason, is divided and isolated into two separate groups. These groups are in different environments, and thus face different environmental pressures. Over time, they will adapt to and evolve in their own environments independently of one another and eventually become two different species.

The concept of a species is actually a little abstract and difficult to define in all contexts, but most generally, we can differentiate species by organisms that can't successfully breed with one another. They may be sexually incompatible (they don't fit), or simply can't produce offspring when they do have sex. Some different species can produce offspring, such as a donkey and horse, but the offspring (a mule in this example) are infertile, which means in a biological sense that the breeding wasn't successful, as it doesn't produce viable offspring that can continue the gene line.

Now, let's address some common points of confusion.

Evolution is a result, not a being

You'll sometimes see even scientists personify evolution by saying, "Natural selection chose..." or "Evolution dictates that...". Evolution didn't "choose" anything, because evolution is not a sentient force deciding a developmental path for an organism any more than weather decides when it's going to rain. I think most people consciously understand this, but if you aren't careful, thinking of evolution as some overseeing controller can poison your understanding of the process. Evolution doesn't make choices, evolution is what happens to the gene pool when the most successful breeders have babies and pass along successful genes.

I think that this personifying of evolution as some sort of thinking, learning, deciding force is responsible for why many people can't accept it as a valid process. They look at the human eye, for instance, and assume that its immense complexity is itself evidence that nature couldn't be responsible for building it, as if nature is incapable of creating immensely complicated structures. They're ascribing human limitations, like the need to learn and focus, to a natural process.

Just don't allow yourself to underestimate nature. Remember that natural processes resulted in our immense galaxy full of 100,000,000,000 stars, and a universe containing 1,000,000,000,000 such galaxies. It does things that are completely impossible for us to fathom all the freaking time.

Evolution isn't trying to produce a "perfect" anything

If you misunderstand any aspect of evolution, this is probably it. Evolution doesn't follow a path, and it's not looking to produce some biologically "perfect" specimen. We are not on a rail system toward becoming a transcendent energy being. Not all monkeys are destined to become human-like, and not all fish are destined to walk on land, and not all bacteria will eventually become fish. Evolution doesn't care what we become, only that we adapt to the current environment as best as we can.

This is a misconception I actually see a lot in the literary world, especially in science fiction when we're reading about "the perfect predator." Remember the peppered moths? Their evolution was a response to the environment. It didn't produce some supermoth that could simply destroy the factories or anything. To produce something like the xenomorph from the Alien franchise, you would need an incredibly hostile environment that required an organism to become a murder machine in order to survive and reproduce.

Now, it's entirely possible that an organism that had evolved specifically for a certain environment to be incredibly well-suited for other environments when introduced. This can lead to it becoming an invasive species. Cats, for instance, have been utterly decimating Australia since their introduction in the early 1800's. These adorable little predators have caused the extinction of quite a few species. Nature didn't create cats to be a super-predator, but Australia's local wildlife had not evolved any defenses against them, so in Australia, cats are basically evolutionary monsters.

A true pinnacle of evolution only means that the creature has reached a very successful body type for its environment. For instance, check out the hagfish. It's a fairly "simple" animal that looks like an eel and doesn't even have true eyes or a spine. Yet based on fossil evidence, it's looked pretty much the same for 300 million years (which means it watched the dinosaurs come and go). That doesn't mean evolution has stopped acting on the hagfish, but so far, it hasn't needed to develop anything radically new in order to survive. Basically, every time evolution tries something new, the hagfish says, "Nope, I'm good" and continues doing whatever it is hagfish do all day.

So yes, your evolutionarily "perfect" animal secretes slime when threatened. Bring on the movie deal.

Macroevolution vs Microevolution

I am trying to stay out of the evolution debate in this article, but I have to be honest and say that when you hear these terms outside of a biology lab, it's usually by those seeking to deny that evolution occurs. In these arguments, microevolution represents small changes that can be observed in a lab setting, while macroevolution represents large changes, such as the evolution of humans from monkeys.

Really, there is no difference between macroevolution and microevolution, except for the time period over which you're making the observation. The idea that microevolution only applies to what can be observed allows a creationist to avoid evidence they can't disprove. It's as simple as that.

Evolution works subtly. In almost all cases, what we're going to see are a bunch of small changes that eventually lead to a big change. You may not notice it as you're watching it, but when you compare the before and after photos over a few million years, the changes become apparent. It's like watching meat cook.

Remember that individuals don't evolve. The changes happen when the genes are passed to offspring, from generation to generation. It follows, then, that organisms that have very short lives can show evolutionary changes much more quickly, because they have offspring much more quickly (shorter generations). The peppered moth will have children once or twice a year, and bacteria may reproduce once every few minutes, so we can see generational changes happening in these species very quickly.

Humans, on the other hand, have a generation once every 20-40 years, so it takes us a long time to respond to environmental changes. We can't watch it happen within our lifetime, since a human lifetime is only a couple of generations long, but don't be fooled. There is no functional difference between the terms "microevolution" and "macroevolution," at least in the way you're likely to see the terms used or use them in your own work.

What about human evolution?

First up, I want to say that this picture is probably responsible for more confusion than anything else regarding evolution in human beings:

The problem with this picture is that it depicts a linear progression and only shows a very tiny part of the evolutionary picture. This leads to the nonsensical question as to why there are still monkeys if monkeys evolved into humans. In reality, that monkey on the far left (or perhaps the monkey behind him) branched into two different species: humans and chimpanzees. We're both results from that same timeline, but the above picture doesn't show it. This one does, though:

If you don't see it yet, think of the first picture as being entirely contained in the circle around "humans" in the second picture. All you see is the line that eventually became humans, but that circle doesn't encompass the chimpanzee line, or any of the other branches in our evolutionary lineage.

Chimps aren't destined to become humans. Humans and chimpanzees share an ancestor, which branched off into the two different species due to different environmental pressures. Really, everything that is alive today is on the same evolutionary level. We may have evolved in different ways, but chimps and hagfish aren't "less evolved" than we are. They simply found different ways to be successful in their environment.

Humans are still evolving, but as you might guess, our capacity to manipulate the environment is giving us the ability to change how we evolve. For instance, humans have developed the ability to keep people alive who in nature wouldn't have normally survived to sexual maturity. This leads to the survival and propagation of certain genes that normally wouldn't have been passed on. In addition, we don't respond to the weather like we used to due to our indoor lifestyles, nor are our bodies typically having to respond to the types of diseases we had to face in the wild.

Basically, because we can manipulate our environments, genes, and breeding potentials artificially, it's very difficult to predict the path of human evolution like we can with organisms out in the wild. Our environment is in some ways more static and in other ways more erratic than we've ever experienced in our evolutionary journey. But make no mistake; we are evolving constantly, and every new child is a new step in human evolution.

The Missing Link(s)

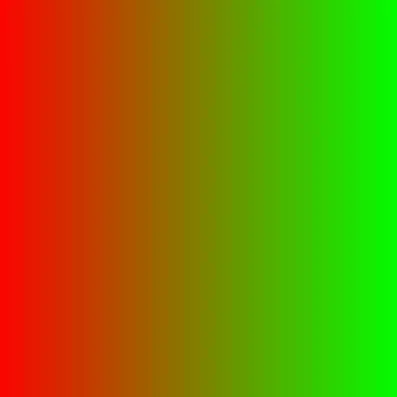

Another common plot element in fiction is that of the "mysterious missing link." To illustrate the issues with this concept, let's take a look at this color gradient, which shows the progression from red to green:

Now, if I wanted to be silly and document the "evolution" from red to green, I could draw a horizontal line and put dots on it, say, one centimeter apart. Each dot represents a "species" of color as it progresses from red to green. But what about the color species in-between the ones I've marked? Well, I could look at those too, and put a dot every half-centimeter instead, which should give us twice as many species. But what about the ones in-between those lines?

The process of speciation works the same way. One species becomes another species through multiple generations in a process that may take millions of years and result in many different intermediate species, such as the progression from single-celled organisms into humans. The concept of a "missing link" is the mysterious species in-between some set point early on and humanity. But you see the catch, right? Even if we had a pretty good picture of monkey-to-human evolution (which we do), there will always be gaps in the record where we missed some generations.

So do those missing links matter? Well, in terms of demonstrating evolution, no, not really.

See, our main way of establishing animals that went extinct before human written record is fossilization, a process which is incredibly rare. In fact, less than 1% of organisms that have ever lived are indicated by the fossil record. It almost always requires some hard tissue, like bone, and a very special set of environmental circumstances before fossilization can occur.

Because of the limitations of fossil records, we have to work by connecting the dots. We're not always right, but we've gotten pretty good at it, and have all sorts of neat genetic tools available to us. Missing links don't disprove a particular evolutionary path any more than missing points on our color gradient would disprove that red can gradually fade into green. If you have enough of the dots, you can make some pretty good guesses from there.

The bottom line

Evolution doesn't usually play as a central tenant in fiction, but is rather used as an explanation for the swamp monster or why a human was born with psychic powers. Given that many people only have a rudimentary understanding of evolution anyway, you may not receive much attention when your evolutionary biologist character blurts out that humans evolved from chimpanzees.

I can occasionally deal with side-stepping advanced science in order to advance a plot, but the fundamentals of evolution are not difficult to understand or write about, and you don't have to be responsible for spreading the misunderstandings about this already-contentious topic. Perhaps it frustrates me when people misuse evolutionary science because I see it as almost a social sin, the propagation of ignorance that is ultimately affecting how people live their lives and how, at least in the US, children are receiving their educations.

If you don't believe evolution occurred, then fine, argue to your heart's content. But if you're going to use evolution in your story, at least use it right. Think of the children.

Do you have an idea for my next science-themed article? I'm taking suggestions! Drop me some topics in the comments, and if I like it, and feel that I either understand or can research it well enough to explain it, your idea can be the next IMOS article. Also, feel free to call me out if you spot an error anywhere; I'd rather have a perfect article than a reputation for being perfect.

About the author

Nathan Scalia earned a BA degree in psychology and considered medical school long enough to realize that he missed reading real books. He then went on to earn a Master's in Library Science and is currently working in a school library. He has written several new articles and columns for LitReactor, served for a time as the site's Community Manager, and can be found in the Writer's Workshop with some frequency.