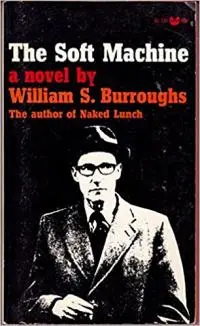

A friend of mine, let’s call him Christopher, summed up his feelings on the Beat Generation by saying he “liked the idea of the movement” much more than the actual fiction that propagated it, finding a majority of the collective body merely literary flotsam. He didn’t go so far as the attributed Truman Capote quote, “That’s not writing, that’s typing,” and credited the bunch minimally as a few one-trick ponies. I disagreed. And after several games of backgammon, and a couple of rounds of Jack & Coke, Christopher challenged me to defend The Soft Machine by William Burroughs—knowing damn well that’s a daunting hurdle even when sober. Still pumped up on the sweet Tennessee honey whiskey, it went, loosely, something like this:

Some novels are famously Sisyphean to ascend, like James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). But for shovel-wielding enthusiasts, a little digging can unearth treasures from what at first appears to be literary chaos. Not so with The Soft Machine (1961). By its very construction using the cut-up technique, it’s a disorienting, kaleidoscopic briar patch. The novel defies you to like it, and if we could magically evoke a personality for this off-the-rails experiment it might snarl back, “Fuck off!” I mean, just consider this seemingly undisciplined passage:

You wouldn’t believe how hot things were when I left the States—I knew this one pusher wouldn’t carry any shit on his person just shoot it in the line—Ten twenty grains over and above his own absorption according to the route he was servicing and piss it out in bottles for his customers so if the heat came up on them they cop out as degenerates—So Doc Benway assessed the situation and came up with this brain child—

“Once in the Upper Baboonasshole I was stung by a scorpion—The sensation is not dissimilar to a fix—Hummm.”

So he imports this special breed of scorpions and feeds them on metal meal and the scorpions turned a phosphorescent blue color and sort of hummed. “Now we must find a worthy vessel,” he said—So we flush out this old goof ball artist and put the scorpion to him and he sort of turned blue and you could see he was fixed right to metal—These scorpions could travel on a radar beam and service the clients after Doc copped for the bread—It was a good thing while it lasted and the heat couldn’t touch us—However all these scorpion junkies began to glow in the dark and if they didn’t score on the hour metamorphosed into scorpions straight away—So there was a spot of bother and we had to move on disguised as young junkies on the way to Lexington— …

The book continues in this ostensibly random flow, except for one chapter, until the very last. Feel free to start with the final chapter and read in reverse and the song would echo the same. But the ‘music’ is where it’s at in W.B.’s hands, highlighting a dystopian world, all savage, devoid of one ounce of sentimentality. We don’t know exactly what’s going on but like a nightmare on speed that keeps making quark leaps to the next horrific ordeal, we listen on, hoping to gain some insight. But after it’s over, and just like a dream, we are left with only corrosive fragments.

Absolutely impossible to talk narrative in any traditional sense. It’s a bizarre, twisted landscape that needs to be experienced firsthand. Within a few pages, first chapter at most, many readers will bail, or, like me, return more than once. However, if they make it to chapter six, titled “The Mayan Caper”, they will find a linear narrative that is unfortunately dull for the simple reason we have lost the timbre we have grown accustomed to ab ovo. In its place we begin reading an ordinary plot about a secret agent that manipulates time to stop evil Mayan priests. I’ve always wanted to take that chapter and scramble it like the rest. In trying to serve a purpose, it ends up serving none.

William Burroughs along with Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac were the driving force of the Beat Generation. Saviors—to a restless generation held hostage by the biddable 1950s who eagerly consumed Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (1959) along with Ginsburg’s Howl (1955) and Kerouac’s On The Road (1957), the triumvirate that cements the ‘one-trick’ Christopher referred to. Lunch was a seminal work that challenged censorship of the era and, originally, Burroughs conceived The Soft Machine as a sequel to The Naked Lunch before launching it as book one of The Nova Trilogy that eventually included The Ticket That Exploded (1962) and Nova Express (1964).

William Burroughs along with Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac were the driving force of the Beat Generation. Saviors—to a restless generation held hostage by the biddable 1950s who eagerly consumed Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (1959) along with Ginsburg’s Howl (1955) and Kerouac’s On The Road (1957), the triumvirate that cements the ‘one-trick’ Christopher referred to. Lunch was a seminal work that challenged censorship of the era and, originally, Burroughs conceived The Soft Machine as a sequel to The Naked Lunch before launching it as book one of The Nova Trilogy that eventually included The Ticket That Exploded (1962) and Nova Express (1964).

Machine’s inspiration was from Burroughs’s friend, painter Brion Gysin (1916-1986) who had chanced upon the cut-up method when slicing up newspapers, though, it was nothing new. The Dadaist movement is the fulcrum on which this subgenre rests, nearly forty years before the Beats, poet Tristan Tzara, on the spur of the moment, famously offered to create a poem by pulling words at random from a hat. His instructions for making a Dadist poem: “Take a newspaper. Take a pair of scissors. Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem. Cut out the article. Then cut out each of the words that make up the article and place in a bag. Shake gently. Then take out each of the scraps, one after the other, in the order in which they left the bag. Copy conscientiously.”

Burroughs though is credited with popularizing cut-up, and he saw something in the format that went beyond. A purity, if you will, that the text interrupted, rearranged, can get to the truer meaning of the work. Yeah, that’s a tough sell unless you are on a "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" trip. But what does come through is the tempo. These short sentences with heightened description: “Orgasm crackled with electric afternoon,” “Zero eaten by crab,” and “Heavy Metal” (that’s right, before Steppenwolf, Black Sabbath, or Led Zeppelin, Burroughs coined the phrase—he also minted “Blade Runner”) are ripe for the Twitter generation that doesn’t often delve beyond a few hundred characters.

In “Vladimir Nabokov and the Problem from Hell,” [The Guardian, 2009] Martin Amis discusses Nabokov’s abundant theme of nympholepsy and asks where in all of literature would one find other instances of such “wayward fixity.” His astute, as always, answer looks at “Lewis Carroll, William Burroughs, the Marquis de Sade—to find an equivalent emphasis: an emphasis on activities we rightly and eternally hold to be unforgivable.” But exactly what activities are we talking about with Burroughs? Undoubtedly the edification of drugs in the Eisenhower era shocked the monkey, as did his wild abandon sex talk.

Bill and Johnny we sorted out the names but they keep changing like one day I would wake up as Bill and the next day as Johnny—So there we are in the train compartment shivering junk sick our eyes watering and burning and all of a sudden the sex chucks hit me in the crotch and I sagged against the wall and looked at Johnny too weak to say anything, it wasn’t necessary, he was there too without a word he dipped some soap in the warm water and dropped my shorts and rubbed the soap on my ass and worked his cock up me with a corkscrew motion and we both came right away standing there and swaying with the train clickety clack clack spurt spurt into the brass cuspidor.

Not love, mind you, but cold, prodigiously mechanical sex … that had to disconcert the Howdy Doody gang. Burroughs just didn’t give a crap. He wrote what he wanted, and that autonomy allowed him to reach much farther than many of his contemporaries. The Soft Machine is one of the clearest examples of his devil-be damned-virtuosity. Far from perfect—and indulgent of the author’s fetishes—the book stands out as an avenue of expression on a literary road where too many voices blend together.

In case you are wondering if I changed Christopher’s opinion, the answer is no. Though who could blame him … Burroughs’ Soft Machine certainly is not for everyone.

About the author

David Cranmer is the editor for BEAT to a PULP. His writing has appeared in The Five-Two: Crime Poetry Weekly, Live Nude Poems, Needle: A Magazine of Noir, Macmillan’s Criminal Element, and Chicken Soup for the Soul. He’s a dedicated Whovian who enjoys jazz and backgammon. He lives in upstate New York with his wife and daughter.