So you think the research for your novel is tough, huh? Searching through library stacks, poring over LexisNexis results, conducting interviews with willing participants... Boo-frickin'-hoo. You don't know tough until you've faced lynching, been held hostage in a piss-covered stairwell by a gang, had yourself committed to a madhouse, or eaten a guy or two in a Peruvian jungle. These badass authors and their dangerous immersive research techniques put the rest of us to shame...

![]() 'Gang Leader For A Day' by Sudhir Venkatesh (2008)

'Gang Leader For A Day' by Sudhir Venkatesh (2008)

What happens when you saunter into one of Chicago’s roughest housing projects to ask gang members to take a multiple-choice survey featuring questions such as “How does it feel to be black and poor? A. Very bad, B. Somewhat bad, C. Neither bad nor good…”? Here’s a hint: It doesn’t involve number-two pencils. First-year University of Chicago grad student Sudhir Venkatesh knows the answer because he did exactly that in 1989. Within minutes, there was a gun pointed at his head.

He spent the next 24 hours in a urine-soaked stairwell, held hostage by members of the notoriously violent Black Kings gang, who told him that the only way to understand them was to live their lives. He took it as an invitation. That's sort of like telling someone, "Yeeeah, I'd love to let you crash while you job hunt, but it's such a small apartment that my stuff barely fits in here," only to come home and find them beaming because they "solved your space problem" by burning all your belongings. Still, it seems to have worked out for Venkatesh.

For nine years, the once-naïve sociology student remained embedded in the projects, where he witnessed brutal beatings, shootouts, and ambushes of rival gang members. He survived by befriending a business-savvy drug-dealing gang leader who helped him understand urban poverty, gang hierarchy, large-scale drug operations, survival instincts, and what it’s like to live with the constant threat of violence.

![]() 'Black Like Me' by John Howard Griffin (1961)

'Black Like Me' by John Howard Griffin (1961)

Though courts had started overturning Jim Crow laws, the civil rights movement had a long way to go in 1959—particularly in the South, where signs reading, “whites only” hung in restaurants, restrooms, waiting rooms, and above drinking fountains. The signs sound like the worst thing ever until you realize that lynchings were still fairly commonplace. Dallas native/white dude John Howard Griffin wanted to understand the challenges of being black in the South, so he embarked on an extreme regimen to rid himself of his whiteness. He consulted with a dermatologist, took a mess of skin-darkening drugs, spent up to fifteen hours a day under a UV lamp, covered spotty areas of skin with dye, and chopped off his hair. Once satisfied that he could pass for a black man, Griffin hopped a Greyhound bus and traveled through Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.

During his “personal nightmare,” he endured “hate stares,” insults, scorn, and humiliation. He failed to find even the most menial job. He witnessed the self-loathing and anger of other blacks. The journey was supposed to last six weeks. He made it only four before breaking down, rushing into a “colored” bathroom after a near-brawl to scrub his skin raw then taking refuge in a monastery. His nightmare was far from over though. When he returned to Texas, he was hanged in effigy. After receiving death threats, his parents, wife, and children went into exile and fled to Mexico.

Far from the “obscure work of interest primarily to sociologists” that Griffin expected to write, Black Like Me has been translated into fourteen languages, included in high-school curriculums, and turned into a 1964 film starring James Whitmore. More than 10 million copies have been sold.

![]() "Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing" by Ted Conover (2000)

"Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing" by Ted Conover (2000)

When it comes to badass research methods, Ted Conover could be on this list several times. Hell, he could’ve taken over the whole list. But let’s not get greedy, Ted. He’s ridden freight rails across America with “hobos” for Rolling Nowhere; he’s snuck across borders with illegal Mexican immigrants for Coyotes; he’s driven a cab in Aspen to document the lifestyle of the wealthy for Whiteout; he’s monitored highway checkpoints with Israeli soldiers for The Routes Of Man, but today we're focusing on his one-year stint as a correctional officer at one of America’s most notorious maximum-security prisons because of all his gigs, it is the one he still dreams of years later. The one he calls the most demanding. The one that distanced him from his family, strained his marriage, and caused him to tell The New York Times: “I have never before on a daily basis, for months at a time, got up and thought, ‘Am I going to get hurt today?’”

Conover wanted to see the system from the inside, so he requested permission to shadow a guard at New York’s Sing Sing Prison. His request was denied. Many writers would’ve given up, moved to another topic (maybe, I dunno, “A Day In The Life Of A Trapeze Artist” or something), but not Ted. No, he spent four years trying to get a job with the Department of Correctional Services. When he was finally hired, he completed a boot-camp-style training program and spent a year working at the facility—escorting prisoners, breaking up fights, and issuing orders to some of the nation’s most violent criminals.

Newjack was a Pulitzer Prize finalist and winner of the 2000 National Book Critics Circle Award in general nonfiction, but was it worth it? Conover told The New York Times, “You come home having done things that don’t come from the better side of you and you feel dirty.” Every day, Conover dealt with mentally ill patients, rape, drugs, rage, tragic stories, and the flaws of the penal system, ultimately concluding that it’s easier not to ask questions because “under the inmates’ surface bluster, the cruelty and selfishness, was always something ineffably sad.”

![]() 'Keep The River On Your Right' by Tobias Schneebaum (1961)

'Keep The River On Your Right' by Tobias Schneebaum (1961)

If you are sitting at your desk, nibbling leftover pizza with hot-dog-stuffed crust, any of what we’ve talked about so far probably seems inconceivably difficult, but listen, you ain’t heard nothing yet. Tobias Schneebaum’s book is about his journey to the Peruvian Amazon where the NYC-based artist immersed himself in the ways of tribal living to the point that he went on a murderous rampage of a neighboring village and helped cannibalize the village’s men. Let me say that again: He ate some guys.

He set off into the jungle in 1955 with no gear, no companionship, and no map. He should have been eaten by an anaconda within minutes but instead he found his way to a Catholic mission where he hung out until a native stumbled in, mumbling that his tribe had been attacked. All the women and children were taken. All the men were murdered. Schneebaum reckoned that the best way for a defenseless Full Bright Scholar like himself to handle the situation was to set off in search of the aggressors. I can’t imagine what kind of drugs he must have been on to come to that conclusion, but he needs to share with the class. Searching for the attackers, he ran into the Amarakaire tribe and settled in. For seven months, he got really comfortable with the tribe (by this, I mean he banged most of them in massive orgies), participating in their ceremonies, singing their songs, going hunting, and ritually slaughtering other human beings. Obvi. Let’s be honest, the whole thing has a lot of train-wreck appeal. They made a documentary about it in 2000. Have fun with that.

![]() 'Ten Days In A Mad-House' by Nellie Bly (1887)

'Ten Days In A Mad-House' by Nellie Bly (1887)

Like Ted Conover above, Elizabeth Cochrane (aka Nellie Bly) could take up several spots on a list like this. She was an early practitioner of immersion journalism and extreme research. By the age of 21, she’d gone undercover in factories to document the treatment of female workers and spent six months in Mexico to cover the challenges of living under a tyrannical czar. Later, she penned the book Around The World In Seventy-Two Days (suck it, Jules Verne!), which sent her on a 25,000-mile journey with only the dress she was wearing, a coat, and a few changes of underwear. On the way, she swung past a leper colony and stopped to buy a monkey…because why not?

But Bly’s most important legacy—because of its effect on the treatment of mental patients—was her book Ten Days In A Mad-House. In 1887, after reading reports of rampant abuse at New York City’s mental institutions, Bly (then the ripe old age of 23) took it upon herself to uncover the truth by having herself committed. She began by spending time in front of the mirror, contorting her pretty face into vacant expressions for practice. "Far-away expressions have a crazy air,” she wrote. Once she’d mastered the crazy-eyes, she quit bathing and took her show on the road. It took only one night of deranged ranting at a boarding house before she was on the boat to Blackwell’s Island, the nation’s first municipal mental hospital.

During her ten days in the institution, she experienced countless horrors: rancid food, filthy water, numbing cold, dirty linens, patients tied together with ropes, scurrying rats, frigid bath water poured over patients’ heads, abusive nurses, beatings, hard benches and mandatory hours of mandatory silence, stillness, and isolation. “What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?” she asked. Bly’s courageous undercover work led to a grand jury investigation, an additional $1 million in annual funding, changes in the way exams were conducted, and vast improvements in the treatment of the insane.

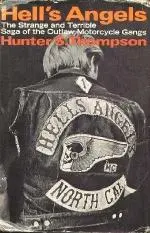

![]() 'Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs' by Hunter S. Thompson (1966)

'Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs' by Hunter S. Thompson (1966)

What list of extreme research tactics would be complete without mention of Hunter S. Thompson, the founding father of Gonzo journalism? What started out as an assignment to write an article about the Hells Angels for The Nation quickly turned into Thompson's first book deal. For more than a year, he dove into the subculture of the club of motorcycle enthusiasts (or violent gang, depending who you ask)—inviting members into his home, drinking and drugging with them, recording details about fights and sexual escapades, riding hundreds of miles alongside them—until he was "no longer sure whether I was doing research on the Hell's Angels or being slowly absorbed by them." The trust he built with members earned him unprecedented access to a group that was, particularly at the time, greatly feared by the public at large. That worked out until he got his ass kicked for telling one Hells Angel that "only a punk beats his wife and dog."

Thompson was the first to embed himself in the Hells Angels for a book, but he wasn't the last. More recently, former federal agent Jay Dobyns abandoned his entire life to infiltrate the upper ranks of the group and write his 2009 book No Angel: My Harrowing Undercover Journey To The Inner Circle Of The Hells Angels. Dobyns's account paints a more violent, dramatic picture of the bikers as the author morphs from a clean-cut dad to a full-fledged Hells Angel named Bird over the course of his 21-month operation. When his identity was revealed, his family dealt with death threats and eventually lost their home and all of their belongings in a house fire caused by arson.

What do you think of books based on immersion journalism? Not all of them involve the threat of death. There are light-hearted examples like AJ Jacobs's Year Of Living Biblically and My Life As An Experiment or Stefan Fatsis's Word Freak: Heartbreak, Triumph, Genius, And Obsession In The World Of Competitive Scrabble Players. Others, like George Orwell's Down And Out In Paris And London and Barbara Ehrenreich's Nickle And Dimed focus more on mainstream society than on dangerous subcultures. What are some of your favorite books along these lines?

About the author

Kimberly Turner is an internet entrepreneur, DJ, editor, beekeeper, linguist, traveler, and writer. This either makes her exceptionally well-rounded or slightly crazy; it’s hard to say which. She spent a decade as a journalist and magazine editor in Australia and the U.S. and is now working (very, very slowly) on her first novel. She holds a B.A. in Creative Writing and an M.A. in Applied Linguistics and lives in Atlanta, Georgia, with her husband, two cats, ten fish, and roughly 60,000 bees.

'Gang Leader For A Day' by Sudhir Venkatesh (2008)

'Gang Leader For A Day' by Sudhir Venkatesh (2008)

'Black Like Me' by John Howard Griffin (1961)

'Black Like Me' by John Howard Griffin (1961)

"Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing" by Ted Conover (2000)

"Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing" by Ted Conover (2000)

'Keep The River On Your Right' by Tobias Schneebaum (1961)

'Keep The River On Your Right' by Tobias Schneebaum (1961)

'Ten Days In A Mad-House' by Nellie Bly (1887)

'Ten Days In A Mad-House' by Nellie Bly (1887)

'Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs' by Hunter S. Thompson (1966)

'Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs' by Hunter S. Thompson (1966)