With the holiday release of Catching Fire, the second installment in the Hunger Games franchise, it's clear that YA dystopias still rule not only the bookshelves, but the box office, too. Up next is Divergent, another series seeking to cash in while the gravy—er, gruel?—train is still in town.

Dystopias are nothing new: Ray Bradbury, George Orwell and H.G. Wells were churning them out long before 25-year-old Divergent author Veronica Roth was a twinkle in her parents’ eyes. Even YA dystopias have been around for a while. John Christopher’s bleak Tripods Trilogy, first published in the Orwellian year of 1984, continues to haunt me as an adult years after I first read it in elementary school.

Film has long loved a bleak future culled from the literary world. A Clockwork Orange, The Warriors, Blade Runner, Children of Men, I Am Legend. Insert your favorite here.

With the rise of the YA Dystopia, its fire lit by Suzanne Collins, now even classics are getting some love from Hollywood. Enter Z for Zachariah, Robert C. O’Brien’s atmospheric and utterly creepy story of survival and obsession in post-holocaust America. Published in 1974 after the author’s death, the film (starring Chris Pine of Star Trek fame) is due to be released in 2015.

So what’s changed? Why is Hollywood—and by extension, why are we—suddenly so smitten with the dark and distant future?

Pretty Young Things

We love to see sweet young things suffer. Let’s take another look at that earlier list. What’s missing (with the minor exception of Children of Men)? Women. The old vanguard of Hollywood dystopias is chock-a-block full of scruffy, testosterone-fuelled antiheroes. Malcolm McDowell, Harrison Ford, Clive Owen: manly, dirty, devious, depraved, and probably not smelling so fresh.

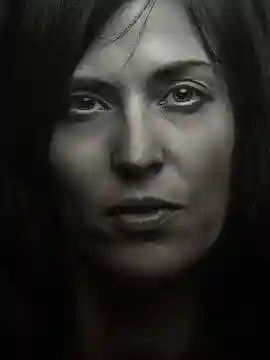

This new brand of dystopia offers a dramatic change in the form of the young heroine. Sure, Katniss is surviving off bread allotments and rabbits, but that doesn’t mean she can’t be pretty. Beatrice may be, well, divergent when it comes to personality, but with Shailene Woodley onscreen I suspect she’ll be right up most people’s dark alleys. Scott Westerfeld’s Uglies series, now in development, gives us a whole rotten world full of hotties.

I’d argue that Lori Petty’s Tank Girl adaptation was the first film to break the mold, but she doesn’t quite fit into the current craze. A bit too old. A bit too silly. A bit too interested in...kangaroos.

No, we like our heroines young, with perfect skin and unquestionable morals, ready to toss that fantastic hair over one shoulder and do what needs to be done.

And that ain’t pretty. These girls are going to be talked down to, stalked, held captive, and beaten within an inch of their lives. There will be hair pulling and mudslinging and blood and tears.

The New Yorker recently ran a column on the YA ingénue phenomenon. I disagree with the trickster concept, and think the new YA heroines are more delicate than that. We the viewers want the delicate, we want to see tears. It underscores everything else when they rise up and kick ass. These girls are tough as glass: break them, and they will cut you.

The lure of the fragile-but-fighting girl is universal. It turns men on, tapping into the Neanderthal centers of the brain which crave hair-pulling and crying. And it empowers women: you can’t beat us down, no matter how small and insignificant you might think us to be. Young women are stronger now than they’ve ever been, taking charge of their bodies and minds. You may as well give away tickets to Divergent with the HPV vaccine.

The Real World is Just As Bad

We need hope. In the grand tradition of dystopias, hope is, if not nonexistent, an elusive and fleeting thing. Not so when a plucky young thing is at the helm.

Gone is the lonesome protagonist’s death at the hands of society/monsters/aliens. Gone is the moral decay that will never be scrubbed clean. These fresh-faced ladies will not be going quietly into that good night, but stomping their society to pieces in the hopes of creating something new from the rubble.

And let’s face it, the here-and-now isn’t such a great thing. We don’t have money, or jobs, or reasonable healthcare. A lot of free America isn’t so secure in its freedom. The US is indebted to China and doing nothing to polish its bully image. Obama’s Between Two Ferns appearance was funny and refreshing, yes, but felt a bit too much like something you’d see on the Panem newsreels. There’s not much out there that gives us a glimmer of hope as to how this will all shake out in five, ten years.

So, let’s revel in the badness. Let’s bring the future here in all its decrepit glory and see if we can’t imagine the worst to make room for the best. Let’s go to the movies.

Ah, Youth

We want to be young again. Sixteen stinks, but how many of us would trade what we have as working professionals of a more advanced age, to have that sense of newness again, if just for a moment? I can tell you that there are days where the burden of saving the world looks far more appealing than that of a career, retirement plan, and mortgage.

The heroines in these stories are innocent, fragile, and the perfect vehicle for ourselves. We feel their pain, we sympathize with them, and in turn they let us walk a mile in their size-six boots. Yes, they may be fighting an impossible evil. They’re frequently close to death. But there’s also something untouchable there, that feeling of invincibility that only comes with being young. Two misfits find each other in these bleak worlds, and the rush of first love is ours again after being long forgotten and buried under all those things that come with capital-L Life.

Even with great responsibility, there is a freedom at work in these stories. Katniss takes responsibility for her family, her sister; it’s not forced on her, as it might have been were she older. She has that choice. Z for Zachariah’s Ann takes responsibility for stranger John Loomis when the world (and to some unspoken degree, Loomis himself) is telling her to look out for herself first. The older we get, the less say we have in our responsibilities. How sweet the freedom to choose seems, looking back.

YA Dystopias comfort us by showing us the world can get infinitely worse, yet that it’s possible to make it so much better. They give us a heretofore unheard of protagonist—the sweet young thing—and, in doing so, show that presupposed “weaklings” can actually wield more power than mighty societies. And they’re a time machine for our own weary psyches, letting us remember what it is to be young, with a whole world—no matter how bleak—in front of us for the changing.

So, are you on the dystopia train to nowhere? What draws you to (or repulses you from) them?

About the author

Emma Clark is assistant class director and columnist at LitReactor.

She studied Japanese and marketing at the University of Texas, then went on to study chemistry just for fun. Along the way she has worked as an analyst/buyer in home furnishings and collectible toys, camera assistant, video editor, book editor, ghostwriter, veterinary technician, bouncer, publicist, artist's model, fashion stylist, and figure skating coach.

Her speculative short fiction has twice been runner up in Lascaux Review's flash fiction contest, has appeared in Devilfish Quarterly and Pantheon Magazine, and will be published in an upcoming anthology on women's bodies. She is currently staring daggers at a manuscript.

Emma loves single malt scotch, animals, home renovation, travel, and auto racing (in no particular order). She lives in Hollywood.