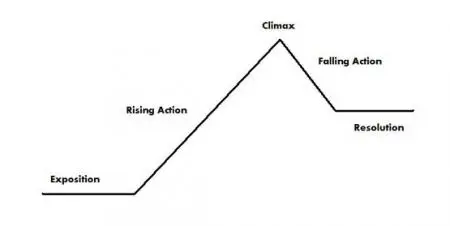

One of the first things students learn in creative writing classes is that the plot of any short story ought to follow a five point structure, sometimes called Freytag’s Pyramid. You can see it here:

![]()

Image via brittanyekrueger

It’s not wrong.

But it also shouldn’t be first.

The pyramid, while useful later on, is not where you ought to start when composing a story. It doesn’t help much with the initial writing process.

The most important thing to consider when putting together that very first draft is consistently giving your characters challenges to overcome.

The Scottish writer Kevin MacNeil once described these to me as hurdles: the main character must always be faced with hurdles. As long as the character is facing these hurdles—not necessarily clearing them, but somehow confronting them—the reader will stay engaged and the plot will move forward.

So when you confront the blank page in front of you, think only of hurdles for these two reasons:

First, it keeps the action going, the tension high. Second, it’s manageable. Looking only as far ahead as the character’s next challenge gives you, the writer, an achievable goal when you sit down to write. If you’re thinking of the falling action or denouement, you might only see a giant void between where you are and where you want to be. Then you may start filling pages just to fill them until you get there. Then your story will be boring and bloated and not do what you want it to do.

Say your story is about a bad relationship, and your protagonist, Jane, has just confronted her boyfriend, Alex, and told him it’s over. This is where it’s tempting to think of how Jane ends up, how the upshot is that she’s better off without Alex and has a good chance at finding happiness. But that’s looking too far ahead. The real question while composing is “what happens next?” not “where does Jane find herself at the end of the story?” In this case, how does Alex take it? Not well, I’d imagine, or the story is probably boring. So the next hurdle is how Jane handles Alex’s reaction. After that Jane might feel lonely or miss Alex, and be tempted to go back. Or she may jump too far into her newfound freedom and make a mistake with a new guy, with a friend, etc.

The pyramid, while useful later on, is not where you ought to start when composing a story.

She’ll get where she’s going, but that’s hard to see while writing. The next hurdle—you can always see that. And when you’ve dealt with it, the following hurdle always seems to be within sight as well.

When you’re done with that initial draft and ready to revise, then it’s time to use the plot pyramid. First, make sure your story has all the elements: point of conflict, rising action, climax, falling action, denouement. Articulating these elements to yourself helps you understand your story better, and may help you catch plot mistakes that you made in the drafting process. (Spoiler alert: there are mistakes. There are always mistakes. For all of us.)

Then, edit as necessary to make your story better fit the plot pyramid.

This is where it gets tricky.

As you go through this editing process, you’ll probably see that your story isn’t in proportion to the plot pyramid you see above. Come to think of it, most of your favorite short stories aren’t either. “Hills Like White Elephants” by Hemingway has a full paragraph of exposition to ease the reader into the story, but “The Harvest” by Amy Hempel dunks you so far under water with its first sentence that your ears pop. “Runaway” by Alice Munro has rising tension almost until the very last moment, but the tension in “Cathedral” by Raymond Carver rises gradually, if at all, before the climax.

That’s all OK. While the concepts put forward in the pyramid are sound, the proportions they take differ in each story, and there’s no rule for that. Some stories have long expositions, some have none at all. For some the climax is right in the middle, for others it’s at the end. If you plot out some of your favorite short stories according to the pyramid, you’ll see what I mean. The important thing is to make sure all the elements are there in your story, even if they’re not so neat and clean as a little black and white chart. What good story is, anyway?

Finally, as you’re going through this drafting and revising, trust yourself. You’ve read tons of short stories, you’ve seen their plots. Your mind knows how a good plot should work. Sure, some attempts are horrific failures and should be buried deep in our Dropbox folders where only the NSA will ever find them, but most aren’t. Trust your creativity and intuition to do some work.

Only think about hurdles. Then a pyramid.

Then you probably have a pretty good plot for your story.

Related: Robert Grossmith guides you through the process of writing a short story

About the author

Joshua Isard is the author of a novel, Conquistador of the Useless (Cinco Puntos Press), and his stories have appeared in numerous journals including The Broadkill Review, New Pop Lit, and Cleaver. He studied at Temple University, The University of Edinburgh, and University College London.

Joshua directs Arcadia University’s MFA Program in Creative Writing, and lives in the Philadelphia area with his wife, two children, and two cats.