Many writers talk about the authorial toolbox when trying to explain certain methods to achieving technical and narrative excellence. Tools are important. They provide the storyteller with implements that cut, measure, and smooth the shape of the tale. To borrow George R.R. Martin’s analogy, both the gardner and the architect require skills that have proven effectiveness. Tools that are both sharp and fine, trusted and heavily practiced. They cannot only be learned about in an abstract sense, but they must be gripped by the writer’s own hand; used regularly. Much has been said about the writer’s toolset. Less has been said about the materials.

To determine scope, the gardening fantasist, for example, must consider the soil of their story, decide how long and how deep the rows of their narrative must be. So too, the architect must move away from the blueprint and consider what character can be a capstone and what characters comprise the supporting arch. The deeper the writer digs into the craft, the greater the spectrum of stone they can use to build towering structures that are both strong against besieging critics and beautiful to the genre tourist.

Tools are important.

Materials equally so.

For me, one of the most reliable narrative materials is family. For the gardener the family structure can be used like a trellis, a lattice of people that allow the ivy of the story to grow.

Family connects us.

The architect can see family members as pillars upon which the story can stand; pillars can be tall or short, sincere or merely a facade.

Family shapes us.

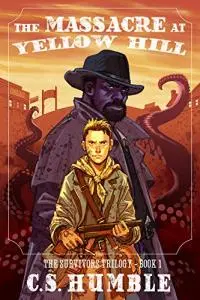

In my debut novel, The Massacre at Yellow Hill, I knew at the outset that I wanted to write about the unique struggle a widow living in the Old West would experience while raising two children. I also knew that I wanted to write about monster bounty hunters, vampires, starry wisdom cults and secret societies. In my first draft I quickly realized that all of the “cool shit” I wanted to put in my book wouldn’t matter if readers didn’t care about the people. So, I built my little Weird Western with that indelible marble: family.

Family is a difficult material to build with, but when the writer does it well, the sunlight of time cannot bleach out the clear, defined lines. Family is difficult to write about because it is so very personal to each of us. We have, all of us, known the pain of familial loss or betrayal. We’ve known the young stresses and anxieties that come from being lonely children, siblings, or orphans. Many of us also know the deep fear of being a parent, and the high pride it affords. Grandparents, foster parents, spouses, and children, each one provides the writer a material that can be used to affect the reader in tremendously cruel or wonderfully uplifting ways.

Afterall, who doesn’t remember that moment in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary that annihilates the reader just under half-way into the narrative? George R.R. Martin’s entire Ice & Fire world is built around the political and emotional constructs of nuanced family groups that range from well-meaningly flawed to terribly abusive. The reader connects with those relationships. Joe R. Lansdale has done a particularly wonderful trick in the familial bond he’s built up over the years between the two, down-on-their-luck and trouble-finding protagonists of his Hap and Leonard series.

Families are a mess: Build them that way

Families, either blood-borne or chosen, provide the writer a deep mine of enduring material.

So, how do we do that? How do we build family units in our fiction that engage the reader and feel real?

For me, family dynamics come down to two things: truth and consequences.

When building your family units and the characters that comprise them, ask yourself what truths do those families hold dear and what secrets do they keep? Are those secrets open or deeply kept for fear of what the truth would bring to light?

Was Charlie’s mother an alcoholic?

Was Charlie’s mother an alcoholic?

Why did Juanita’s father leave them when she was only five years-old?

How did Erica respond the first time she saw her father hit her sister?

Janet’s grandmother was so kind to her, but why was she never allowed to stay the night at her house? And why was the basement door always locked after Janet’s grandfather disappeared?

These questions work in any form of fiction because they represent real, tangible experiences that every reader can sympathize or empathize with. And those are just examples from a child’s point of view.

For parental characters, the same exercise adds a different quality of question. One question in particular in my own work comes from the mindset of my widow from The Massacre at Yellow Hill, Tabitha Miller. Tabitha, who was left in poverty to raise two children alone believes certain things about the world before and after the death of her husband. His death changes the way she sees the world and thus changes the way she parents. Those consequences change the truths she believes in, and further still change the way her children see and interact with her. With consequences come rising tension and from that tension the other characters interacting with Tabitha see their own beliefs about her reshaped or reinforced.

We could say that this is a general rule when dealing with all relationships in our stories, but the family unit provides a unique character dynamic: intrinsic familial love.

A child may love a parent in a way that is unfailingly endearing, at least for a time. That intrinsic love returns, albeit in another form when the character becomes a parent. For a parent, love becomes unfailingly sacrificial. Marital love is similar to the latter in some cases, but, like the others, runs across a whole spectrum of how family life evolves after major events.

However, we can also take that familial love and use it for tumultuous ends. For example, what does it mean for a child to unfailingly love an abusive parent? Or, what does it say about a parent character who deeply failed to protect their child? These situations breathe life into our characters because they are real family dynamics, and the more real the family inside your story, the more real your characters will be to the reader.

Buy The Massacre at Yellow Hill at Amazon

Buy A Red Winter in the West at Amazon

About the author

C.S. Humble is an award-winning American novelist and short story writer. He lives in East Texas. His latest novel, the second book in his Weird Western Horror 'Survivors Trilogy", A RED WINTER IN THE WEST can be purchased via Amazon. He can be found on Facebook, Twitter (@cshumble) and at his website. Read a review of A RED WINTER IN THE WEST at the ever popular THIS IS HORROR to see if you're into C.S.'s style.