Internet fury has become a commonplace of our daily lives, so ubiquitous that Jon Ronson wrote a book about it, so routine that this same book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, was one of the books we talked about on our return episode of the Unprintable podcast. In Shamed Ronson talks to people who have experienced the internet in full-on cobblestone-hurling riot mode and lived (some just barely) to tell the tale.

Rob Hart, who picked the book said roughly (I’m paraphrasing) about his reaction: It’s scary as a writer to think you might say the wrong thing and have this happen to you.

And it is scary, like the idea of stubbing your toe is scary. The internet is a dark room and most of us are wandering around in it barefooted. That room is full of large and unforgiving objects we cannot see, in the form of other people’s sensitivities, and colliding with one of those objects is almost bound to happen eventually.

But should we be scared? On the face of it, yes. As Ronson demonstrates, when shit goes wrong on the internet, it can go wrong very fast, occasionally with life altering consequences. But if you take a closer look at some recent examples of writers falling foul of virtual opinion, you can see that if you do happen to excite the online lynch mob, there are ways to survive the experience and live to write again.

Anthony Horowitz, author of the most recent Bond novel Trigger Mortis, said in a newspaper article that he feels Idris Elba is ‘too street’ to play James Bond. Horowitz said many other things in that article—including that for the first time Bond gets dumped by his love interest—but you wouldn’t have known it because every piece about the story ran with the idea that Horowitz based his comment on the fact that Elba is black. In other words, ran the subtext, Horowitz said Elba is too black to play Bond. This is not what Horowitz said. In fact, he explicitly comments that Elba’s skin colour is not the issue for him. He simply thinks of Elba as conveying a grittier demeanor than the world usually associates with Bond, famed for his taste in suits and ability to pair wine and cheese.

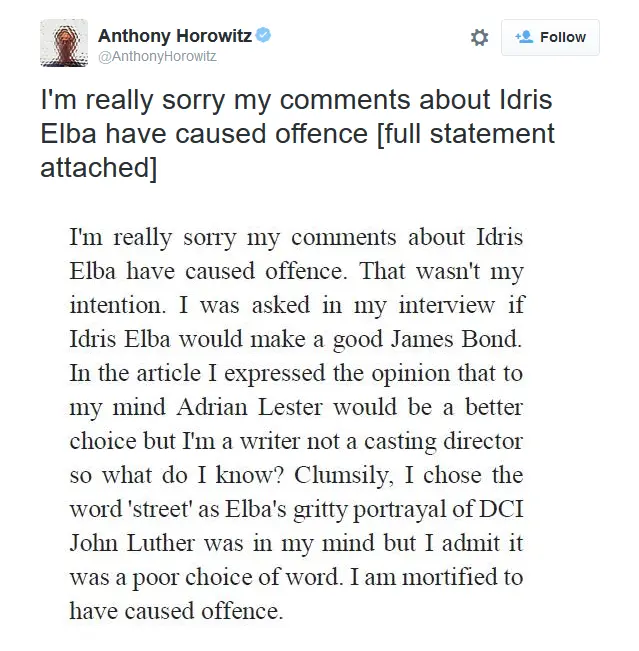

Faced with a howling mob of eggs on Twitter, pitchforks at the ready, Horowitz posted this clarifying statement:

This is a sorry man. He’s so sorry he’s mortified. If you had to condense this statement into one sentence it would probably read Please don’t set me on fire.

So is an apology the only way to respond if you tread on some internet toes? Not necessarily. Take a look at the even more recent case of Meg Rosoff, award winning children’s author who dove in on a Facebook status dealing with diversity in kid’s lit. Librarian Edith Campbell posted a link to this article. There are just too few books for all our marginalized young people said Campbell in her status. Rosoff was quick to comment: There are not too few books for marginalized young people. There are hundreds of them, thousands of them she said going on to claim that children’s publishing is becoming ‘too literal’. You don’t read… Alice in Wonderland to know about rabbits Rosoff explains. Diversity is not an agenda.

Can you hear the virtual pitchforks being hoisted to shoulder height?

The row spilled over onto Twitter, because if Facebook is the bar where we like to have a drink after work, Twitter is the street outside where we go when someone spills a beer or pinches the wrong bum. Sleeves were rolled up. Coats were taken off. Rosoff refused to back down. Unlike Horowitz she didn’t post an apology, she doubled down. Books don’t have a job, she said in a further comment on the thread, except to reflect the world as the author sees it. I agree with her: the moment you try to make a book reflect a particular point of view, you’ve failed as a writer, because your audience will sense the effort. Books for children, in particular, need to avoid the temptation to preach or to push home a point, because young people, being at the stage when they are discovering their own opinions about the world, resent being force fed an agenda even more than adults do.

Rosoff’s opponents weren’t very happy with this. Myles E Johnson, the author of Large Fears commented – I’ll leave you to guess where (hint: it was Twitter) – that privileged folks do not know the very real effects of underrepresentation and that was why he hadn’t waited to get a book deal, but had gone straight to crowdfunding for his project. The cynical amongst us might wonder if the reason he didn’t try mainstream publishing is because his book isn’t very good, but let’s leave that discussion for another column and ask instead what the end result was for Rosoff. You’d think that if a writer like Horowitz felt he had no choice but to grovel, she was courting disaster by defying the baying crowd. But did she actually end up burned at the virtual stake?

Answer: no. No bomb threats. No doxing. No press release from her publisher announcing the sad end to their long relationship. Rosoff sailed through it all and even scored a little extra publicity to boot.

But why? Both authors are white and made comments which irritated people who are not white. Why did one have to apologize and one got to walk away with her head held high?

The difference is that Horowitz made his comment off the cuff and Rosoff didn’t. She has a strong, well thought out opinion on diversity in books. Horowitz, as he admits in his statement, is no expert on casting decisions. Which is why he had to back down and Rosoff didn’t.

Lesson #1 for Making the Internet a Less Scary Place: Write What You Know

Remember how on the stones handed down by God to Charles Dickens, one of the writing commandments was that you should write what you know? This also applies to your online content. It’s not a blanket rule, but applies most strongly to certain subjects, and we all know which ones these are. If you have an opinion on a hot button topic, you can offer it, but be sure you have facts or a well thought out argument first. It also helps to have some legitimacy in the form of personal experience or background. And by legitimacy I do not mean ‘knowing someone who’. Everyone knows someone who.

But it’s more or less impossible to stay off hot button topics completely, especially if you want to use social media to showcase your wit, as many writers do. Unless you want to spend all your time on Twitter talking about your pets, or the weather, or solemnly retweeting pictures of sunsets with quotes that sound like condolence cards, you’re going to want to occasionally crack a joke or two, and the thing about many jokes is that their impact depends on straying into forbidden territory. And forbidden territory contains all the hot button topics we are not supposed to talk about.

Ronson gives two very sobering examples of what can go wrong when people make bad jokes on the internet. Justine Sacco made an ill-considered tweet about AIDS. Lindsay Stone made fun of a sign at a war memorial. Both of them lost their jobs. Does this mean that for writers, the internet must become a fun-free zone?

Not necessarily. If you want to be funny but also careful not to offend, you could workshop all your material, like the writers of sitcoms do, or test it on an audience first, but given that most of us don’t have the time or energy or patient enough friends for that, there is a simple rule which will help.

Lesson #2 for Making the Internet a Less Scary Place: Be Funny, But Also Be Nice

This is about tone as much as anything. While it makes sense to steer clear of one liners that concern people who are not of the same gender, sexual orientation, BMI or ethnic background as you, it also makes sense to try not to hit too sharp a note. You want your audience to smile, not wince. Unless you want to be deliberately provocative, keep your ridicule gentle and remember the power gradient should always point upwards – it always reads better to choose a target with more privilege than you have.

Sacco got into trouble because she (appeared to) choose a target we generally think of as having less advantage than her – black Africans. She fell victim to her own poor choice of words (she was aiming for sarcasm but, because Twitter doesn’t have much nuance, came across as sincere) and because she hit too sharp a note. AIDS isn’t funny, no matter what your ethnicity. Stone also hit a bum note, not because she mocked a sign asking visitors to keep quiet, but because she picked a war cemetery as the locale for the mockery. If the sign had happened to hang in a modern art gallery, no one would have bothered to so much as warm up a bucket of tar. Dead soldiers make a poor target for jokes. They also have grieving relatives. Be funny, but also, be nice.

But what if it still all goes wrong? What if you post online with legitimacy and funny-but-niceness and STILL someone takes offense? What then?

This is what happened to Meaghan O’Connell when she wrote this article for The Cut on male children’s writers as objects of crushes. This is fun-pokery of a gentle kind, a little in the same vein as this column in The Toast. I had no problem with it, being partial to a little light male-objectification of my own, but lots of other people did, their reaction being ably summarized by this tweet:

Oh dear.

Did O’Connell retreat into hiding? Did she lose her job, her friends, her livelihood?

She did not. Instead she published this on her blog.

Lesson #3 for Making the Internet a Less Scary Place: Know When You Have Fucked Up

The internet is a dark room full of furniture with hard corners. We wander around in it barefooted and sometimes we’re going to stub our toes. When we do and someone calls us out on a joke or a post or a comment, it’s worth remembering that this person has also stubbed their toe – on the opinion or wisecrack you just put out there. It’s very tempting in that situation to reflexively deny you’ve caused offense. It’s also tempting to reflexively apologise. But an unexamined apology doesn’t cut as much ice as one that thoughtfully addresses the issues. O’Connell’s reaction is an example of how to know when you have fucked up and how to respond. In the end, she came out ahead.

Don’t be scared of the internet. It has its abusive corners. More should probably be done by those who profit from the various platforms we use to keep that abuse in check, but like most places people gather, the online world is a warm and friendly place. Stay aware of the scope of your legitimacy, keep your humour gentle, listen to comments and make a judgment about whether criticisms are valid and you should do OK.

Like Horowitz, O’Connell apologized, but she did it with enough grace that she could, like Rosoff, leave the debate with her head high. She didn’t fall into the trap of getting defensive. She didn’t cower either. Instead she listened. She responded. She survived.

And so will you.

About the author

Cath Murphy is Review Editor at LitReactor.com and cohost of the Unprintable podcast. Together with the fabulous Eve Harvey she also talks about slightly naughty stuff at the Domestic Hell blog and podcast.

Three words to describe Cath: mature, irresponsible, contradictory, unreliable...oh...that's four.