The truth about superheroes is there’s a reason there’s never been one. Not just the lack of super-powered being that can fly and bend steel, but a vigilante like Batman that rushes out into the night with expensive gadgets and advanced training. The reason is that superheroes are a power fantasy, and even a fascist fantasy at that. With Trump’s ascendency to the presidency, it’s clear that superheroes could be both a sign of inspiration in troubled times, or a reflection of a greater sickness at the heart of Americans. I prefer to choose the former, and a book that came out this year fills me with hope.

That book is Last Night, A Superhero Saved My Life. Edited by Liesa Mignogna, an editorial director of Simon Pulse who focuses on novels for teens and tweens, it compiles essays written in the past or specifically for the book. That includes contributions from Neil Gaiman, Jodi Picoult and Brad Meltzer, amongst others.

These essays discuss more the idea of superheroes and how they’ve worked as inspirations. There’s Jamie Ford’s “Daredevil, Elektra, and the Ninja Who Stole my Virginity”, detailing how Frank Miller’s classic run helped the author get over his first love. Then there’s “Swashbuckle My Heart: An Ode to Nightcrawler” by Jenn Reese that explains how the furry X-Man helped a struggle with body issues growing up. Then there’s Ron Currie Jr.’s “Weapon X” and its musing on Wolverine and positive masculinity.

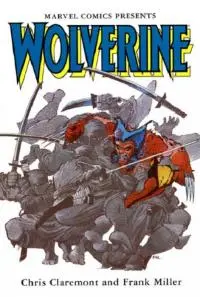

Currie breaks down Frank Miller and Chris Claremont’s Wolverine mini-series from 1982 and how it represents a positive, aspirational masculinity. This is the famous series that sees Logan head to Japan to confront his fiancée Mariko who says she cannot marry him. The result is a war against a clan of ninjas, including Mariko’s father Shingen, and an acceptance of the repercussions of violence. The conflict inherent is Wolverine wants the discipline of a samurai, but sometimes the animal helps him win the day. Currie takes this and shows how it is an inspirational story in its own right, and through the power of storytelling how fiction can provide not just hope but tools. These tools can be helpful in opposition to fascism that has resulted from a pervasiveness of “toxic masculinity” in the United States.

This idea of fascism is something encapsulated very well by Glen Weldon in his article, “Superheroes and the F-Word: Grappling with the Ugly Truth Under the Capes” for NPR. Published on November 12, 2016, just a week after the election, it considers how superheroes are only good for people because the characters themselves, usually square-jawed white men, are inherently good and will make the right choices. But their philosophies are flawed power fantasies, the way little boys view the world in terms of simple black and white, good and evil.

This idea of fascism is something encapsulated very well by Glen Weldon in his article, “Superheroes and the F-Word: Grappling with the Ugly Truth Under the Capes” for NPR. Published on November 12, 2016, just a week after the election, it considers how superheroes are only good for people because the characters themselves, usually square-jawed white men, are inherently good and will make the right choices. But their philosophies are flawed power fantasies, the way little boys view the world in terms of simple black and white, good and evil.

Weldon wrote The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture (a must-read for Batman fans, comic book fans, or just anybody) and knows his stuff. He’s delved deep into the problematic aspects of a character like Batman, a billionaire, old money, white cisgendered heteronormative male 1%er, that knows best for the masses, especially those impoverished minorities that will surely be fixed by a punch to the face. But even if Batman knows best, it’s only because he’s Batman. Or as he puts it, while the earliest incarnation of Batman always defended the rich, others like Superman were much more progressive in their standing up for the little guy.

This changed, however, with World War II, and “In the process, the visual iconography of superheroes — which, comics being comics, is 50% of the formula, remember — melded with that of patriotic imagery. This continued for decades after the war, as once-progressive heroes like Superman came to symbolize bedrock Eisenhower-era American values — the American Way — in addition to notions of Truth and Justice.” And that’s true, we won WWII—and in the process solidified ourselves as the biggest and baddest but also the most morally upright. This, however, led to the United States becoming the police of the world, always chasing that noble cause.

There’s a reason WWII, as opposed to World War I, is used so often as a backdrop for stories in popular culture. There was a clear good guy and a clear bad guy, whereas the earlier war was a cluster of forged treaties and questionable choices. And superheroes, or their writers, are similarly chasing that last noble war, with clear-cut heroes and crystal-clear villains. But that’s not the real world, and why superheroes shouldn’t be aspirational in the literal sense, but can be inspirational in a more ephemeral sense.

As the introduction to Last Night, A Superhero Saved My Life puts it, “This is not a book about superheroes. It’s a book about the relationship between humans and superheroes—the three-dimensional, and sometimes life-sustaining dynamic between us and the iconic characters who started out on the pages of four-color comic books.”

Take, for instance, Currie’s “Weapon X”. The author, whose 2009 novel Everything Matters! chronicles an individual that from the moment of their birth knows when the world is going to end, contrasts a narrative from his young life against the struggle of Logan, the Wolverine himself, from the mini-series that put him on the map. Currie confesses that his comic book knowledge didn’t extend much beyond the indie and fringe books of the early ‘80s such as Maus, The ‘Nam and Love & Rockets, but he hung out at the comic book store often and that’s where he saw the cover of Wolverine #1.

Unlike some of the things I thought unassailably cool as a kid, the cover of Wolverine’s first series has not been diminished by age or perspective. It’s such an arresting image, still: our hero, claws deployed and wearing an expression of rapturous fury, locked in hand-to-hand with half a dozen ninja. His hair is swept up into a dual-peaked pompadour, the virility of which is matched only by its improbableness, and his trademark muttonchops flare raggedly from his jaw like the beard on a Scottie dog.

Virility. All young American men are raised that we have to be constantly proving ourselves, whether that be in sports or romance or leadership. And all of that is a way of proving our potency. And yet the waters have been muddied in recent years with the awareness of “toxic masculinity”. This “boys will be boys” mentality, in which violence is always the key and sex is a prize to be taken, has always existed but only recently has there been movement to educate against its insidious ramifications. And while the last 25 years or so seemed to evolve the modern male into a more sensitive, self-aware individual, the backlash has been obvious and damning.

As Currie points out, ‘Not too long ago, everyone’s favorite serial provocateur Camille Paglia executed one of her patented, gleeful cannonballs into hot water when she told the Wall Street Journal that “primary education does everything in its power to turn boys into neuters.”’ Paglia, who has been described as an “anti-feminist feminist” is, of course, talking about the dichotomy of political correctness and its detractors, while defending the old-fashioned masculinity of John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, and all those other guys your dad probably loves. And while Paglia and other “lightning rod” feminists argue that boys suffer from a lack of strong masculine role models, Currie posits that manliness is innate and shouldn’t be denied.

Boys like to fight. Men need to fight. This is Currie’s argument, as he articulates when first seeing the cover of that comic book: “I saw in Wolverine not inspiration to become something other than what I was, but rather confirmation of what I already knew I wanted to be.” He subsequently charts his rise from a self-professed “sissy” to someone that stands up to a bully, even if it doesn’t result in any cinematic fisticuffs.

And while it’s easy to see the correlation between Currie’s thesis and the current state of the modern American male, there is nuance in his argument. The modern, ostensibly white, American male is told they are powerful and important, but are consistently undercut and robbed of any power. Movies and pop culture portray us as inherently good and noble and strong, and yet our real lives are spent wallowing behind desks and being told we’re the problem, we’re the past and not the future.

And that’s why Donald Trump is the next President of the United States. He appealed to the base, primordial feelings that reside in the gut of all American men. Feel emasculated and weak? He talks big and struts around like the cock of the walk, and you can too. Except that it’s all talk, and it’s toxic talk at that. It’s the kind of bully dialectic and ideology that leads to wars and fascism. But being the better man, the bigger man, doesn’t mean walking away from a fight according to Currie. It means being like Wolverine.

Would it be overstating things, or otherwise foisting an unreasonable amount of cultural weight on a mere comic book character, to suggest that Wolverine might be the ideal for postfeminist men seeking a balanced masculinity? A masculinity that strives for goodness while acknowledging, and sometimes giving quarter to, the beast within? A masculinity capable of being gentle while retaining both the willingness and ability to hand someone a beating if he’s got it coming? A masculinity that celebrates the talents and autonomy of women, yet also makes provisions for supporting and, if need be, protecting them?

The overarching argument is framed by the opening of Wolverine #1, a sequence that Currie dissects in detail. A bear has been rampaging through the Canadian Rockies, and as Wolverine’s best skill is killing he aims to put the bear down. He discovers the bear has been hurt, pierced by a poisoned arrow that has driven him insane. It’s not the bear’s fault, but Wolverine does what Currie believes a man must do:

A man accepts the paradox of mercy; that it sometimes feels, even appears, cruel. A man grabs a shovel, or else stands over the poor creature and raises his boot, does what needs doing. He doesn't feel good about it, except maybe long after the fact, when the sting, and then the ache, of having taken a life goes out of the experience. But here is the obligation, and if he is a man, he fulfills it.

Wolverine tracks the hunter down and finds him at a bar, giving the man an option to turn himself in to the Mounties. Of course he doesn’t, and Wolverine gets to rough the man up, which is what he wanted to do in the first place. But he first gives him a choice, something that Currie muses is the key to being a man. “Understand, this is not a call for throwing the first punch,” he explains, “but of reserving the right to throw a punch if the situation ultimately calls for it, a right that I would argue has largely been taken from us.”

And that’s the key difference between Donald Trump’s brand of masculinity and Wolverine’s. Trump’s defensiveness and aggression throws the first punch, imposing his will without regard for those that get hurt along the way. Wolverine, however, knows when violence is necessary, and may even enjoy it, but only imposes his will as a last resort.

And that’s the real way that superheroes can save the day, especially with the impending four years. Their brand of vigilantism—punch first, ask questions later—may not be the answer for everyday life, but adapting their lead to real-world problems is definitely an option. In that way, especially for young men that are told to act a certain way in order to be “manly”, we can be like Wolverine.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.