What do Ernest Hemingway, Tom Wolfe, Chuck Palahniuk, Raymond Chandler, O. Henry and Stephen Crane all have in common? Before they were the adored giants of fiction we know today, they were all journalists. Yet for some strange reason, many kindhearted, lit-loving fictionist wannabes, the daydreamers who hope to one day publish novels or poetry chapbooks on par with Steinbeck and Salinger, tend to overlook journalism as a viable means to those ends.

Instead, they'll have mom or dad write them a check for an MFA at some prestigious academy of letters where they'll read and understand literature like never before, but the odds of actually becoming successful in that field are lower than shit. Suggest writing for a newspaper and you’ll receive scoffs. Journalism isn’t real writing.

But there’s a strong argument to be made here, which we’ll see just might strengthen your resolve as a writer. Of course, journalism isn't the only route to becoming a respected wordsmith, but it's a dependable one.

Journalism Will Quickly Build Your Portfolio And Reputation

Successful newspapers and magazines have built-in audiences and like Hungry, Hungry Hippos, they devour content greedily. Getting someone to read your short stories is nearly impossible, but an interview or review is far more likely to grab eyeballs. And people are all too eager to criticize your talent in the comments, some of which can be helpful.

Plus, if you get published, you’ll be working closely with editors who will help you fix and learn from mistakes. That means you’ll be getting more feedback on your writing than you could ever hope from most writing workshops. Add that to the frequency with which journalists practice their writing skills and journalism is invaluable.

Journalism Will Help You Develop Structure And Style

Word count is God in journalism, especially in print. In my early days as a reporter, I despised this regulation, convinced my opinions and stories were too precious to be confined or trimmed. However, I quickly learned to “kill my darlings” and became able to write concisely in most cases. No more beating around the bush – journalism gets straight to the point.

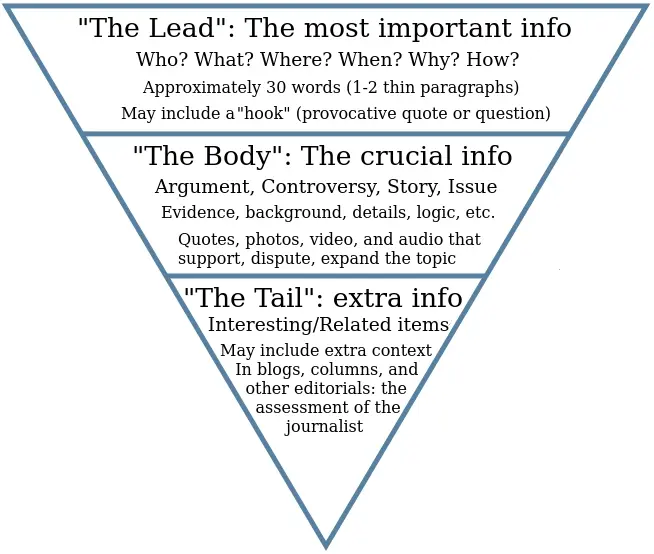

Journalism has many formats, but they all rely on the inverted pyramid in some way. This tool helps you prioritize the info you’re writing about. The opening paragraph, known as the lede, should be able to answer who, what, where, when, why and how in approximately one or two sentences, usually 35 words or less. Writing a good lede takes tons of practice, but a good one will hook your readers and keep them reading.

Applying this technique to fiction is similar. Maybe you’ve heard some writing coaches suggest starting stories off with action or good attention-grabbing sentences. By practicing this in non-fiction, it helps you organize your thoughts and focus on the most important details in the story.

The lede is followed by the body, where the story expands with the second-most important facts. The last part is the tail, which includes scattered minor details that aren’t crucial to understanding what you just read. The idea is that your readers are busy and if they stop reading halfway through your piece, which they might, they’ll still walk away well informed about the situation.

The lede is followed by the body, where the story expands with the second-most important facts. The last part is the tail, which includes scattered minor details that aren’t crucial to understanding what you just read. The idea is that your readers are busy and if they stop reading halfway through your piece, which they might, they’ll still walk away well informed about the situation.

For example, take this recent Reuters piece on the Ukraine riots: “Protesters clashed with riot police in the Ukrainian capital on Sunday after tough anti-protest legislation, which the political opposition says paves the way for a police state, was rushed through parliament last week.”

That 33-word sentence tells you plenty and if you didn’t read further, you would still have a clear grasp of what’s going on. The last sentence in the post, “Russia has since thrown Ukraine a $15 billion lifeline…” is a more nuanced detail that isn’t nearly as important, but it’s still relevant, so it’s tacked on at the end.

Of course, some short story you want published in The New Yorker isn’t gonna be structured this way, but by practicing writing along these lines, you’ll learn how to engage readers quickly and easily.

These guidelines might seem constrictive, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get creative. The Pulitzer Prize website has amazing examples of brilliant, yet typical journalism, but their feature pieces are the crème de la crème. Read through their archives and familiarize yourself with what puts a non-fiction journalism piece on par with the excellent, compelling fiction you dream of one day developing.

Feature stories follow a narrative style closer to a three-part story arc. The focus can be anywhere, but it’s less on events or cause/effect and more on in-depth human interest, character profiles, “behind the scenes” accounts and more. But that doesn’t mean feature writing is without structure. Here, creative outlining is crucial. Writers that don’t outline are generally sloppy in my opinion and if you’re just starting out in this field, you’ll need to find a way to organize your notes so your thoughts aren’t scattered.

Take this VICE article, “The Icelandic Skin-Disease Mushroom Fashion Fiasco,” by Hamilton Morris as an example. In the first paragraph, Morris still has a hook and while it tells you almost nothing about the story itself, it hints enough in a strong literary fashion to keep you reading. The rest of the article has a very straightforward approach (i.e. this happened, then this happened, followed by this…) but ties together so well that it accomplishes both feats of literary brilliance and informative, hard-hitting journalism from a poetic, firsthand experience.

Unfortunately, journalism like this is becoming more and more rare as funds for these types of excursions dry up. All the more reason to familiarize yourself with this type of writing. It’s valuable and people want more of it. When you have these styles mastered, your fiction will start to take on many of the same strengths. There are other forms of journalism, including anecdotal ledes, Q&A format and others, but these are the main two and will get you started.

Afflict the Comfortable, Comfort The Afflicted

Exceptional journalism takes practice, but once you become skilled at it, you should invariably understand what makes a quality story. Furthermore, as a journalist, your job is not to promote your own voice, but the voices of others. In the 1960 film, Inherit the Wind, Gene Kelly famously said, "[I]t is the duty of a newspaper to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” Ideally, you’ll do the same.

This will help you build empathy and see clearly from unique points of view, even with outlooks you disagree with. Beginning writers are often told to “write what you know,” but if you want to expand your horizons, few other educations offer such up close and personal lessons. Additionally, hours of transcribing interviews may help you grasp genuine dialogue.

There are other ways of learning these skills, of course, but journalism can help you craft believable fiction outside your comfort zone. Just ask the multitudes of novelists who got their start with it.

Defeat Writer's Block With Journalism

Writer's block blows. Staring into a blank screen is a writer’s version of Hell, but it doesn’t have to hold you hostage. Assuming you work closely with a publication, you’ll start to develop a “beat,” or area of expertise, and this will become a wealth of story ideas.

A beat is best if it covers a topic that thrills you. For me, my beat is music, so when I started freelancing for New Times, I quickly assimilated myself into the “scene.” Soon enough, it was no trouble finding interesting material to write. And when the muse doesn’t visit, which will still happen occasionally, you’ll learn how to chase her down and hold her arms back until she coughs up a good pitch.

Plus, your editor(s) might shower you with topics that come across their desk, so if you’re having a blank week, you might still get assigned something. It may not always be something you like, so it’s better to learn how to find ideas yourself or find an editor that is cooperative.

That does mean there will be deadlines and lots of them. Don’t be frightened. Being forced to write within consistent parameters will help you develop strong time management skills and, more importantly, instill in you the ability to compose even when you really, really don’t wanna. Being able to write when you’re “not in the mood” is essential if you ever wanna be on the New York Times Best Seller list.

Journalism may take time away from your creative development, but hopefully you’ll find a healthy balance and attack your fiction with renewed energy. If you still don’t find time to write creatively, at least remind yourself that you’re getting paid to write and that’s still better than mopping floors or flipping burgers. Oh, by the way…

Journalism Pays!

Well, sort of. Journalism is not exactly a lucrative career anymore, but before you’re established, it’s far more financially rewarding than trying to live completely off fiction or poetry sales. Plus, once you have a decent portfolio, finding writing jobs will become easier. Some will suck, but hopefully you’ll discover a happy medium.

So, How Do You Become A Reporter?

Glad you asked. It’s fucking easy. I went to school for it, and while I don’t regret doing so, if I could go back I’d probably learn something more financially stable, like chemistry or geology. Then I would use my spare time to write while I paid my bills. Hey, it’s what Michael Crichton did!

I actually didn’t learn much in my classes besides how to write in AP Style and what a good blog looks like. Almost everything else I learned came through trial and error out in the field. Journalism can basically be learned in six weeks using guides online.

For example, I used to be incredibly nervous talking on the phone. Not a good recipe when most interviews are done at your desk (few journalistic interviews are done in person these days, but if you can manage one, it’s much better. Trust me). One of my first assignments as an intern was to call some farmers and discuss blueberry pickin’ season with them (not the most fascinating of topics, but you have to start somewhere). I was so apprehensive, I forgot to ask the farmer his name. Too embarrassed to call him back and ask, I looked the farm up on the internet and guessed who he was.

When the story went to print, I received a chewing-out from my editor because the name was completely wrong and the farmer, incredibly excited about being featured in the paper, was extremely pissed. I was forced to write a retraction. The newspaper never assigned me another story, confining me to updating their online calendar until my internship ended.

After that, I quickly learned how use the phone with confidence. Given enough practice, you will too. Don’t get me started on the time I printed something that was “off the record” or the many other times I fucked up. I’m still learning. Take these lessons on the chin – they’ll probably hurt, but if you pick yourself up, you can thrive in this industry.

So What Do You Need?

A copy of the AP Stylebook, a reliable laptop, a decent digital recorder (I purchased a Zoom H2 for $150 that hasn’t done me wrong in four years) and a decent camera, preferably a DSLR. That’s it! I also suggest always carrying a pen and notebook for scribbling down ideas, which you should do regardless. Using your phone works too, but it’s too easy to get distracted by silly apps and text messages, so I don’t recommend it.

That isn’t everything, of course. Like the Hippocratic Oath, journalists have a code of ethics, courtesy of The Society of Professional Journalists, which covers how to minimize harm, seek truth, act independently and be accountable. I have a copy printed above my desk. Of course, not everyone has virtue *cough cough Lara Logan cough* so try to have some principle and keep your nose clean.

More tips:

• Ask the right questions. Also remember the five W’s and one H: who, what, when, where, how and why. If you write a story and forget a crucial detail like “how the robber got away” or “who he was with” or even mundane details like the model of getaway car or how many shots were fired, your story will suffer.

• Talk to the right people. If you’re shy, don’t worry – journalism can help you overcome that. Avoid the “man on the street” approach, where you ask some uneducated bozo outside the courthouse what he thinks of a situation he has no authority on.

• Be accurate. You’re not Hunter S. Thompson and you’re not writing gonzo journalism (which is embellishing details and putting oneself in the story’s framework.) Sometimes injecting yourself into the story is important, but most of the time, it’s not. If you want to make a relevant point, you should probably find someone who is a bigger authority on the subject and get their opinion.

On the flipside, this technique is often used by slimy reporters who will find someone who agrees with them just to tote their opinion as fact. Learn to recognize this and avoid it in yourself, because it’s not hard to spot. That also means giving both sides of the story, which may mean interviewing someone you dislike, disagree with or is reluctant to speak to you.

• Be ethical. It’s common in modern journalism for reporters to inject their own opinion. You may be tempted to do this (heck, even I do it from time to time) but you should avoid this as much as possible when you’re starting out. Why? You’re still in the process of building your reputation. Until your readers know you and know you well, they frankly won’t give a shit. You’ll come across as hoity-toity, amateurish and egotistic.

Every claim you make needs to be verifiable and you should learn how to include sources. If someone you interview makes a claim, fact-check it – you may catch someone in a lie and keeping folks accountable is part of your job. It should also go without saying that you should avoid exaggeration and never lie. If a young, amateur journalist like you is caught in an untruth, it will forever tarnish your reputation and you can kiss your journalism career goodbye.

• Be persistent. The biggest hurdle you're going to overcome in journalism, at first, is rejection. If you don’t have a bunch of published clippings, few editors are going to want to hire you until you can prove your salt. Be patient with yourself – Rome wasn’t built in a day. Use your rejection as fuel to keep your fire burning and reflect on what works and what doesn’t.

Journalism isn’t without its faults and isn’t going to turn you into Truman Capote overnight. But if you want to find a way to hone your writing skills in a truly practical way, there are few other methods that are as effective. Am I missing something? Let me know in the comments.

About the author

Born in the desert, Troy Farah is a journalist that likes to burn things. His reporting has spanned VICE, Phoenix New Times, Flag Live and others, with fiction published in Sleeping in a Torn Quilt and Every Day Fiction. His website is troyfarah.com where he mostly dreams about the apocalypse.