When one of us professional English majors finally escape from university life, we do tend to get nostalgic for how books are read when they’re assigned. It’s not always easy to engage with a text on your own, especially when it’s an older book or one that’s a challenge. Once you’ve re-read the Harry Potter series for the umpteenth time, you might think your brain could use a little flexing. So you sit down with James Joyce’s Ulysses and realize it’s nearly impenetrable. Except it wasn’t that way in college when you had not just your teacher and fellow students to bounce the book around on, but academic texts that could break it down in insightful and enlightening ways.

Compact and accessible for the layman, books that equate to the college experience come in the form of Twayne’s Masterwork Studies Book Series. Released over nearly two decades starting in 1986, there are hundreds of books in the series. These include The Scarlet Letter: A Reading (Twayne Masterwork Studies Series No. 1), Paradise Lost: Ideal and Tragic Epic (Twayne's Masterwork Studies Series No. 12), and several more from such varied authors as Robert Dale Parker, Peter Raby, Allen Josephs, Ross C. Murfin and Nina Baym. Each book tackles their topic with immersive critical analysis ranging from 100 to 200 pages. One that stands out in particular is Catch-22: Antiheroic Antinovel by Stephen W. Potts, No. 29 in the series.

Catch-22 is the classic World War II novel written by Joseph Heller. Published in 1961, it works as a satire of the war and of war in general. Its lead is Captain John Yossarian, a 28-year-old B-25 bombardier in the Army Air Corps stationed on the small island of Pianosa off the coast of Italy. His mental health has started to unravel, and he desperately wants to get out of the service. That’s, in fact, where the term “catch-22” comes from: the only way to get out of the military is to be proven crazy, but wanting out of the military is the only sane reaction to war. The phrase caught on immediately and has become prevalent ever since. The novel itself was embraced within a decade of its release and accepted into literary canon to be taught in schools and puzzled over around the world.

Potts’s approach to Catch-22 is very much they say, I say. The first 18 pages has sections covering the background of the book, the context for its creation and the critical reaction to it, and the different approaches that have been taken with critical analysis in the past. That means a timeline and some history for Heller, who wrote the book based on his own military service.

The importance of the work is framed around how it’s a reaction to the years following World War II. “By the end of the decade of the fifties,” says Potts, “with its smug, even soporific conservatism, American intellectual culture was restless.” There was a desire for change, change that would be quickly seen in the Civil Rights Movement, anti-war protests and countless other paradigm shifts. But before this there was the Beats, satire and “sick humor,” and the popularity of books critical of American culture and capitalism.

Into the cultural discussion comes Catch-22. The mainstream “mimetic novel” had been declared dead by critics in the wake of Finnegan’s Wake, with said critics looking to France and Europe for something beyond realism. What might have caught their eye is the blurb for Catch-22, describing it as:

Like no other novel we have ever read. It has its own style, its own rationale, its own extraordinary character. It moves back and forth from hilarity to horror. It is outrageously funny and strangely affecting. It is totally original.

And it heralded a wave of new books in the early '60s that represented a new direction in American literature, combining naturalistic detail with satirical and surreal exaggeration, mingling slapstick and gloom, fantasy and history, real issues and two-dimensional caricatures that are comparable to Charles Dickens. This new wave included Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night (1961) and Cat’s Cradle (1963), and Thomas Pynchon’s V (1963).

Reactions at first to the book were fairly positive but mostly perplexed. Critics appreciated the black humor and blend of farce. Some even compared it to the past classics of satire like Voltaire, Swift and Samuel Butler. There were those, however, that saw the novel as offensive, unpatriotic, vulgar and incoherent. Even those that liked it thought it excessive in length, redundancy, comic effects, and in the graphic depiction of sex and gore.

The biggest point of contention was the tonal shift, late in the book, from comedy to violent melancholy. Despite this, critics were attracted to its avant-garde method of laying out the plot. They didn’t quite have the words for Heller’s work yet, however, with postmodernism being only a glimmer in their eyes before the coming of Vonnegut, Pynchon and the rest.

What was a big concern was the aforementioned anti-war message. The American youth were turning against “The Establishment” in ways they never had before. While the college students of the ‘50s embraced J.D. Salinger and Jack Kerouac in sullen, quiet rebellion, by the ‘60s activist readers had been influenced by the satire of Mad magazine and leftist critics like Herbert Marcuse and Paul Goodman. These new novels of social satire functioned as a confirmation bias for those frustrated with the individual facing powerful and faceless bureaucracies. Heller himself argued that the novel was more a reaction to the Cold War of the ‘50s and not any social movements of the ‘60s, but by the time the book was turned into a movie in 1969 it was slotted in line with the likes of Dr. Strangelove and M*A*S*H.

But by the time the book really caught on in the 1970s, what had united critics was the concern over the message and over the “tortured chronology.” With the message, the sudden tonal shift signals Yossarian’s moral wrangling with and ultimate decision to desert. Many saw this as an immoral philosophy to spread.

All of this stemmed from Heller’s stream-of-consciousness method by which he structured the book and his tendency to lean into contradictions. This perplexed those that had become eternally fascinated by the timeline of the book. When is everything taking place? Since Heller took a non-linear approach and presents events with a kind of dream logic, it’s hard to nail down their sequence. The first attempt was by Jan Solomon in the last ‘60s with the article “The Structure of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.” There Solomon attempted to show that two timelines exist in the novel: one a cyclical one revolving around Yosarrian and another, cutting impossibly and absurdly across the first featuring Milo Minderbinder, the squadron’s mess officer, who employs the only appearance of a German in the novel to bomb the American encampment on Pianosa in order to profit from it.

Solomon, however, was ultimately determined to have a faulty assessment of Heller’s chronology, with Doug Gaukroger responding a few years later. His article “Time Structure in Catch-22” dispenses entirely with Solomon’s incorrect reading of the narrative. Gaukroger, according to Potts, does a good job of assembling the sequence of events based on a painstaking analysis of the text. That means a breakdown of the main bombing campaigns of the plot, that being Ferrara, Bologna, and Avignon, and how the careers of Yossarian, Milo and other main characters weave through those bombings. Gaukroger discovers errors in Heller’s timeline, but makes a few mistakes himself.

Clinton S. Burhans, Jr. picked up where Gaukroger left off in 1973, and manages to nail down specific dates for the book. This is all a matter of keeping track of how many missions Yossarian has been on, and things start to become more detailed for the character after April 1944. In this context Burhans discovers more errors on Heller’s part, something later commentator Robert Merrill picks up on. The biggest contribution from Merrill is that when the novel opens with Yossarian in the hospital, he has already been on 44 missions, not the 38 that Gaukroger and Burhans assert.

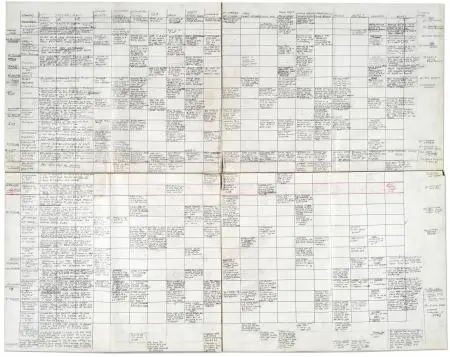

Potts takes a shot at the timeline, composing most of the book around his argument. And his main utilized source is a book released in 1973, an essay collection called A Catch-22 Casebook, edited by Frederick Kiley and Walter McDonald. What this overlooked book contributes is studies of charts that Heller made himself.

What all of this does in a 136-page thesis, Potts takes the reader through the process of being in a semester of a course devoted to Catch-22. The classroom is a microcosm of an ongoing conversation around a subject, and specifically a literature classroom around a book. An argument can’t be made in a vacuum, but must be built on the backs of others. And finding a narrowed focus, in this case the structure of Heller’s book and how it reflects the chaos of war and the fractured mindset of the main character, is key to understanding.

For that reason, Twayne’s Masterwork Studies Book Series is a must for classical novel enthusiasts. Instead of re-reading a favorite again, try seeing it through the eyes of others. A deep dive collected into less than 200 pages will illuminate a text. And for those of us nostalgic for the classroom experience, it’s the closest approximation.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.