Before there was film noir, there was the roman noir, the dark novel. What Americans of the mid-twentieth century called pulp fiction was simply the contemporary incarnation of the dime novel or penny dreadful of the previous century. The lurid stories behind the lurid covers were considered lowbrow trash and indeed, many of them aspired to be nothing but the same. But one man’s trash is another man’s dark worldview, as evinced by the French embrace of these tales from the godless gutter of the New World. It’s no coincidence that we still use the French term to describe the genre; no less than Existentialism’s poster boy himself, Albert Camus, credited James M. Cain’s noir classic, The Postman Always Rings Twice, as the inspiration for his own classic, The Stranger. So it was no surprise at all when, about fifteen years ago, I was prowling through the stacks in a bookstore on the Avenue des Champs-Élyseés and found French translations of the heavyweight champ of American noir writers, Jim Thompson, filling an entire shelf, end-to-end. It was a bittersweet sight. Every one of Thompson’s books was out of print in the U.S. at the time of his death, only to be resurrected courtesy of the Black Lizard imprint roughly a decade later and thus confirm the author’s own prophecy, that he would be posthumously famous.

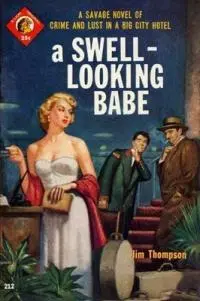

Jim Thompson was born in Anadarko, Oklahoma Territory in 1906. His writing was autobiographical, to a certain extent. Before the oil fields (Roughneck), he was a bellhop with a knack for catering to the shady requests of hotel guests (A Swell-Looking Babe), and readers can see hints of his family history throughout his work, most notably the disgrace of his lawman father. It’s tough to give a cursory overview of Thompson, given that he wrote in excess of thirty novels, to say nothing of his writing for film and television. With that in mind, here are a few highlights, most of which have, conveniently, been adapted to film (some more than once).

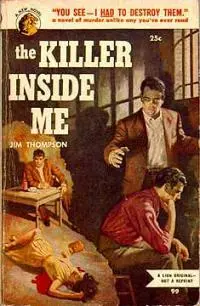

The Killer Inside Me (1952)

We’ll start with the easiest. It was the most recent of film adaptations, but it’s also the most arguably well-known from Thompson’s body of work. The narrator, Lou Ford, is a small town sheriff and is not just corrupt, but a bloodless sociopath. He hurts people for his own amusement and

murders them for little more, except when he’s murdering them to cover his tracks. Some have suggested that this novel was one of the first forays into writing from the standpoint of criminal psychopath; whether that’s true or not, it was certainly one of the best.

murders them for little more, except when he’s murdering them to cover his tracks. Some have suggested that this novel was one of the first forays into writing from the standpoint of criminal psychopath; whether that’s true or not, it was certainly one of the best.

Pop. 1280 (1964)

Though published twelve years after The Killer Inside Me, the two novels are often referred to as siblings by critics and fans of Jim Thompson. Both are told in the first person and narrated by lawless lawmen recounting their small-town body count for the reader. The key difference is that Thompson took the wholesome, toe-scuffing, aw, shucks veneer of Lou Ford (as brilliantly portrayed by Casey Affleck) and cranked it to eleven with Sheriff Nick Corey, who narrates Pop. 1280 with an exaggerated Li’l Abner cornpone dialect that belies his recreational bloodletting. So pronounced is Nick Corey’s hillbilly persona that the only thing more frightening than his appetite for blood (and everything else; both his libido and table manners are formidable [the amount he eats throughout the novel verges on science fiction]) is how much he revels in ripping off his metaphorical mask when confronting a victim.

I’m particularly fond of Pop. 1280, because I think it has one of two particular passages (both Thompson’s) that sum up the noir genre so neatly, it could almost be a manifesto:

“I’d been in that house a hundred times, that one and a hundred others like it. But this was the first time I’d seen what they really were. Not homes, not places for people to live in, not nothin’. Just pine-board walls locking in the emptiness. No pictures, no books—nothing to look at or think about. Just the emptiness that was soakin’ in on me here.

“And then suddenly it wasn’t here, it was everywhere, every place like this one. And suddenly the emptiness was filled with sound and sight, with all the sad terrible things that the emptiness had brought people to… Because that’s the emptiness thinkin’ and you’re already dead inside, and all you’ll do is spread the stink and the terror, the weepin’ and wailin’, the torture, the starvation, the shame of your deadness. Your emptiness.”

That's pure noir, right there.

The Grifters (1963)

The plot behind The Grifters is interesting and fairly straightforward. Roy Dillon* is a con artist. So is his girlfriend. And his mother. Along with the tensions arising from the parties the three have respectively pissed off, there’s a rising tension between Roy’s mother (Lilly) and his girlfriend (Moira) that verges on Oedipal, with respect to Roy. This is not the first time Jim Thompson’s work ventured into such territory. There were similar overtones in A Swell-Looking Babe, as well as a pair of incestuous siblings in his short story, This World, Then the Fireworks.

*The surname Dillon was the pen name Thompson used in some of his early short stories, as well as that of the main character in his first published novel, Now and on Earth, and Frank Dillon, the narrator of A Hell of a Woman.

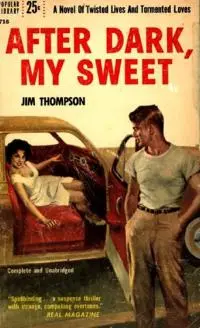

![]() After Dark, My Sweet (1955)

After Dark, My Sweet (1955)

I mention these two novels in succession only because they were both released as films the same year, 1990, heralding the Jim Thompson renaissance along with the Black Lizard reprints. But while the Stephen Frears adaptation of The Grifters was a critical and commercial success, After Dark, My Sweet was largely ignored. That’s a shame because, in my opinion, the latter is not only a better film (which is not to say The Grifters wasn’t any good; it was beautifully done, and Frears did a stunning job making L.A.’s MacArthur Park look very period-noir while making the story contemporary, not to mention the performances of the cast), but is also one of the most faithful book-to-film adaptations I’ve ever seen.

Kevin “Kid” Collins is a homeless drifter living hand to mouth in the hinterlands of the California desert when he’s taken in by a widow as a caretaker for her withering estate. Collins, it turns out, is a former champion prize fighter but by most every measure he acts as though he’s lost by more knockouts than he’s won. Taken for a sap by the widow Fay Anderson, Kevin Collins is roped into a kidnapping scheme by the widow and one “Uncle Bud” (of dubious relation but most definitely a scumbag). And as all things noir must, their plan goes awry.

While Jim Thompson approached storytelling with a journalist’s eye and bare-bones prose, he could also be experimental at times (most notably in Hell of a Woman, when the narrator suffers a break with reality and the ensuing prose veers into William S. Burroughs territory, and The Golden Gizmo which features, yes, a talking dog. Sort of.). In After Dark, My Sweet, Thompson surprises us with a prototypical unreliable narrator.

A Swell-Looking Babe (1954)

Unlike the others I’ve covered here, this one has yet to be touched by Hollywood, to the best of my knowledge. Nonetheless, it’s one of my favorites. Drawn from Thompson’s own experience, it’s the story of Dusty Rhodes (Really, Jim? Really?), a bellhop who has to walk the line between doing favors and running errands for the high- and low-class criminal guests of the hotel, while at the same time keeping his nose clean and doing his part to keep the place “respectable.” As in, no prostitutes. And in 1954, that meant screening lone female guests and being on the lookout for undercover detectives.

As you might guess by the title, one particular guest slips through the check-in screening and all hell breaks loose. On a side note, just as Sheriff Nick Corey’s voracious appetite always stood out as both amusing and puzzling, so here does the sartorial preoccupation of A Swell-Looking Babe’s main character.

As you might guess by the title, one particular guest slips through the check-in screening and all hell breaks loose. On a side note, just as Sheriff Nick Corey’s voracious appetite always stood out as both amusing and puzzling, so here does the sartorial preoccupation of A Swell-Looking Babe’s main character.

Thompson’s body of work makes a thorough survey of everything a rather daunting task. A quick web search will yield plenty of other titles and again, courtesy of Black Lizard, the bulk of Thompson’s novels remain in print to this day. Full disclosure: the obvious omission from the above is The Getaway, which has been twice brought to the big screen, but is one of the few Jim Thompson novels I’ve yet to read. Don’t ask. But in addition to those summarized above or mentioned in passing, there’s South of Heaven (1967), The Alcoholics (1953), Cropper’s Cabin (1952), Recoil (1953), and the list goes on.

For more about the man himself, I recommend both biographies: Jim Thompson: Sleep with the Devil by Michael J. McCauley* and Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson by Robert Polito. Both are excellent; McCauley’s came first, though Polito’s is regarded as “official” by many.

*After you’ve read Pop. 1280, check out the photo of the last page of the manuscript in Sleep with the Devil. You’ll see the very last line that Thompson scratched out, which radically changes the story’s ending.

And as for that second of the two passages that sum up the noir genre, it’s from The Killer Inside Me:

“A weed is a plant out of place. Let me repeat that. A weed is a plant out of place. I find a hollyhock in my cornfield, and it’s a weed. I find it in my yard, and it’s a flower.”

In other words, our moral boundaries are purely arbitrary. That is the black, godless universe for which the genre is named. That’s noir.

About the author

CRAIG CLEVENGER is the author of The Contortionist's Handbook (MacAdam/Cage, 2002) and Dermaphoria (MacAdam/Cage, 2005). He is currently living in San Francisco, California, and completing his third novel.