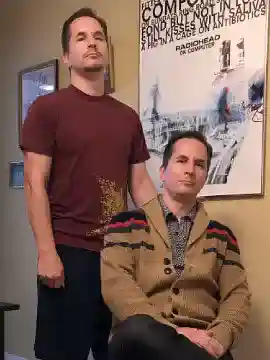

Juan Martinez author photo via author website / Eden Robins author photo by Jeff Kurysz, via author website

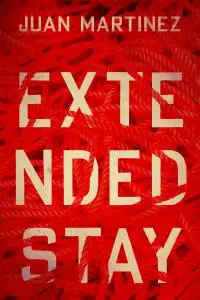

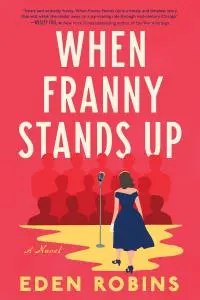

Juan Martinez’s and Eden Robins’ debut novels could not be more different — Martinez’s Extended Stay is a horror novel about the immigration experience, invisibility, and a Vegas hotel that eats people, and Robins’ When Franny Stands Up is a historical comedy about trauma where stand-up jokes are magic. Both authors have a sneaking suspicion, though, that there’s more common ground between funny and scary fiction than you might think. Here they discuss the relationship between humor and horror and how these powerful creative tools can bring us relief and even liberation from trauma and fear.

Eden: Let’s start with a basic question that is probably way more complicated than it seems. Juan, you’ve written both humor and horror. What, in your mind, is the relationship between being funny and being scary in fiction?

Juan: It’s such a good question! And I’m sure I’m stealing a bit of this idea from a film theorist who talked about “cinema of affect,” but I think humor and horror both trigger actual physical responses in readers (or viewers). Like, what we read on the page is what we experience in our bodies a little, with both traumatic frightening stuff and also with funny goofy stuff. Maybe? But I’m also curious as to your thoughts on this, particularly since even though When Franny Stands Up is totally funny, and is totally about (among other things) comedy, it does navigate some dark material—I mean, I could see an alternate version of your novel that’s actually pretty frightening.

Regardless, what do you think? What’s the funny/scary relationship for you?

Eden: I had a very visceral and physical experience reading Extended Stay, which does an incredible job exploring the frightening ways in which the real world intersects with a surreal one. A lot of people talk about the catharsis that comes with a joke’s punchline, or with horror—the idea being that you can play out your fears in a safe, fictional world and then exit that world grateful that it’s not YOUR world. Both humor and horror operate in a kind of simulation that has different rules than our real world. So you can excise a trauma from our reality, plant it in a joke or a horror story and be like, “Let’s see you try to hurt me here.” You can run that simulation and learn new things from it that you couldn’t learn in the real world. In the real world, you’re playing by trauma’s rules. In a humorous or horror story, the trauma and fear is playing by YOUR rules.

I’m curious if you experience that relief/catharsis when you’re writing about these things? Or do you think that’s just an experience you can have as a reader?

Juan: Oh my god! This is such a good question and one I’ve gone back and forth on. Like, for the most part, writing a genuinely horrific moment—one that comes out of nowhere and is sick and gross and out there—all of that is super clinical and detached for me. I’m not scaring myself. I’m just trying to set up stuff to scare a reader who shares a lot of my own readerly interests but is (1) imaginary, (2) not me, but (3) also maybe a lot like me. If I’m being honest and reflecting on what it feels to write those scenes, the truth is that I’m not actually scaring myself. It does feel in some ways like another simulation, different but parallel to the one you articulated so nicely in your answer: how a novel or any kind of narrative is a bounded, controlled space to navigate stuff—often traumatic—that in life is fundamentally unbounded, uncontrolled. So it’s all a long way to admit that relief and catharsis don’t quite occur for me when writing horror. There’s the relief and catharsis of finishing something, of course. But that’s not the same.

Juan: Oh my god! This is such a good question and one I’ve gone back and forth on. Like, for the most part, writing a genuinely horrific moment—one that comes out of nowhere and is sick and gross and out there—all of that is super clinical and detached for me. I’m not scaring myself. I’m just trying to set up stuff to scare a reader who shares a lot of my own readerly interests but is (1) imaginary, (2) not me, but (3) also maybe a lot like me. If I’m being honest and reflecting on what it feels to write those scenes, the truth is that I’m not actually scaring myself. It does feel in some ways like another simulation, different but parallel to the one you articulated so nicely in your answer: how a novel or any kind of narrative is a bounded, controlled space to navigate stuff—often traumatic—that in life is fundamentally unbounded, uncontrolled. So it’s all a long way to admit that relief and catharsis don’t quite occur for me when writing horror. There’s the relief and catharsis of finishing something, of course. But that’s not the same.

I would love to know more of your thoughts on that—on whether you yourself find relief or catharsis in writing humor—but then I’m afraid I’ll be turning into a ChatBot whose primary algorithm is: rephrase and bounce back the question to the human. So I won’t! Here’s a different question, and one that you should feel free to answer however you want. I love Franny’s treatment of gender, down to its classic takedown of the are-women-even-funny bit, but also to how gender inflects family roles and responsibilities, plus issues of pleasure and visibility and all of that: how do you feel about the way humor (as a mode but also as a subject) gave you a way to approach those issues?

Eden: So, when my dad was in the Army, his superior officer (an antisemitic dick) called him out for a uniform inspection. Everything was in order—uniform properly pressed, shoes shined, etc.—and then the officer got this shit-eating grin and said, “Tell me, did you shine the back of your belt buckle? Because the man who doesn’t shine the back of his belt buckle doesn’t wipe his ass.” And my dad, without missing a beat, snaps to a salute and says, “Which would you like to see first, sir?” This is an extremely long way of saying: the humor I grew up with and absorbed is slippery, it elides authority, and provides escape from what otherwise feels like an impenetrable edifice of power and dominance. It is a very Jewish kind of humor, and, I think, of historically oppressed people in general. Its aim isn’t just to speak truth to power, but to expose power itself as ridiculous.

In the 1950s, when Franny takes place, even people who lived within the very rigid rules of gender suffered, much less anyone who fell outside the norm! Humor is an awesome tool to illuminate the lives of folks who had to elide authority and be slippery in order to survive. My characters who live outside gender norms had to make up their own rules and language and community, so there’s a joy and creativity in that slipperiness, too. And having these misfit characters create their own comedy, about their own experiences, was also so important to me. It’s so essential to “punch up” in humor. Not just because it’s the kind and ethical thing, but humor that makes fun of marginalized groups isn’t funny. It’s trying to use the master’s tools (apologies to Audre Lorde) to mimic an art of resistance and rebellion. Ridiculous! Humor is the people’s tool!

This actually makes me think about Alvaro, your main character in Extended Stay, who slipped through trauma to survive, slipped through the cracks as an undocumented immigrant, and sometimes slipped through the actual cracks of the Hotel Alicia. There is something sneaky and slippery (sometimes literally!) about horror in this book. Do you think that horror can also be a tool of rebellion and resistance to power? If so, how did you go about wielding it that way?

Juan: I do think that! And I think that those qualities—sneakiness and slipperiness—go hand in hand with rebellion and resistance, right? As a kind of asymmetrical warfare against well-established systems of oppression? But I’m also thinking that another way to think about these traits and humor and horror is that it’s not just evasive, just off to the side, like the elision you talk about with your dad’s story and with humor at large, but also about this issue of invisibility at the root of who is doing it, who is paying attention, who is being ignored. I’d say that this works in horror in a bunch of different ways, but one absolute way it shares with humor: I feel that when you do either and it succeeds, it’s because you’ve delivered on the affect—you’ve made someone laugh or recoil or both—and then hopefully you get to also deliver on rebellion and resistance. But it’s almost accidental. So much of both humor and horror is about misperception. About the character or the reader or both thinking they’re about to get one thing but getting another.

I feel like all novels have what W.G. Sebald called a “ghost-novel,” like a previously existing book we graft ours to… Is there one for Franny? Or here’s another question, if that one is lame: what are some of your favorite current horror or comic novels?

Eden: In one way or another, I’m always writing with The Neverending Story in mind. It’s been my favorite book since I was a kid (the movie is a poor substitute). It is unabashedly strange, sad and funny and scary and philosophical, and unafraid to be exactly what it needs to be. I’m always striving for that. But one recent book that I hadn’t read until after I wrote Franny but immediately became a favorite is The Trees by Percival Everett. Everett is unbelievable; he can write anything in any style, and this book, to me, embodies the best of what humor AND horror can do when interwoven together. It is bold and shocking and wonderful and I’d never read anything like it before.

Eden: In one way or another, I’m always writing with The Neverending Story in mind. It’s been my favorite book since I was a kid (the movie is a poor substitute). It is unabashedly strange, sad and funny and scary and philosophical, and unafraid to be exactly what it needs to be. I’m always striving for that. But one recent book that I hadn’t read until after I wrote Franny but immediately became a favorite is The Trees by Percival Everett. Everett is unbelievable; he can write anything in any style, and this book, to me, embodies the best of what humor AND horror can do when interwoven together. It is bold and shocking and wonderful and I’d never read anything like it before.

My last question is a twofer! I want to know a) what current horror or comic novels you love! And also, I have a bit of a chip on my shoulder about this, so I want to know b) why you think humorous and horror fiction still isn’t taken seriously as “literature”?

Juan: I LOVE Everett! Dr. No is on my shelf right now. My favorite current horror work is a graphic novel, Junji Ito’s Spiral (small town starts seeing spirals everywhere & then things get weird & unsettling). For comic novels, my all time recent favorite is Elizabeth McKenzie’s The Portable Veblen, and I’m super super excited for the one she’s coming out with this year, The Dog of the North, which I’m pretty sure I’ll love even if the title was not playing off Charles Portis’s The Dog of the South.

I like this last question! But—apologies for being a contrarian—maybe both genres are being taken seriously as literature? Maybe? And—maybe, maybe—they shouldn’t be? I like the idea of working in a disreputable corner of the art world, and my feeling is that we’re awash in great, serious work that is inflected with horror or comedy. (I mean, what is A24 if not a prestige platform for some combo of the two?)

Eden: I could argue about this forever but for the sake of our word count I'll just say this: I think we're much more open to different tones and subject matter in movies than we are in novels, and I’m not sure why? Maybe it’s just the size of the audience for movies vs. novels? I think Everything Everywhere All at Once is a PRIME example of this. You'd never find that mix of genres and tone in a novel, certainly not one that popular. I think in the written word, serious is defined by default as dramatic and realistic. I will reluctantly agree that I like living on the artistic margins too, but that doesn’t mean I can’t grumble about it.

Get Extended Stay at Bookshop or Amazon

Get When Franny Stands Up at Bookshop or Amazon

Juan Martinez is the author of Best Worst American, a story collection published by Small Beer Press and the winner of the Neukom Institute Award for Debut Speculative Fiction. He lives near Chicago and is an associate professor at Northwestern University. His work has appeared in many literary journals and anthologies. Learn more HERE.

Eden Robins loves novels best, but they take forever so she also writes short stories and self-absorbed essays at places like Catapult, USA Today, LA Review of Books, Apex magazine, Shimmer, and others. Her debut novel, When Franny Stands Up, was named a best book of 2022 by the Chicago Reader, a best queer book of 2022 by Autostraddle, and Best Book of the Month by Bustle and Buzzfeed. She co-hosts a science podcast called No Such Thing As Boring with an actual scientist and produces a monthly live lit show in Chicago called Tuesday Funk. Find out more at monkeythumbs.com and on Twitter and Instagram @edenrobins.

About the author

Joshua Chaplinsky is the Managing Editor of LitReactor. He is the author of The Paradox Twins (CLASH Books), the story collection Whispers in the Ear of A Dreaming Ape, and the parody Kanye West—Reanimator. His short fiction has been published by Vice, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Thuglit, Severed Press, Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing, Broken River Books, and more. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @jaceycockrobin. More info at joshuachaplinsky.com and unravelingtheparadox.com.