Don't Write Comics is a multi-part essay about writing comics, understanding what your options are, finding the right artist, and everything you need to do to get a strong comic book pitch package together.

If you’re interested in comics solely because you think it might be easy or that it might be a shortcut to another end (like having a movie made of your comic) let me just stop you right here and point you towards the exit. While it's true that some screenplays get reverse engineered into comics, and then after being successful comics are turned into successful films (30 Days of Night springs to mind), there's nothing "quick and easy" about making comics. In fact, if you’re not well connected to artists (and possibly some publishers) and/or willing to lay out your own money upfront in some cases, then it can be the very opposite of quick and easy. In order to make good comics, I truly believe you have to already love comics. It’s the love that’s going to get you through.

IDENTIFY WHAT YOU’RE WRITING

So you’ve made it this far…which means you either do have a love of comics, or you’ve decided to ignore my advice - in which case I’m not sure why you’re reading on, but whatever, you’re here!

First and foremost, I would suggest identifying what kind of book best fits your idea. Because we are assuming you are not already a well-established comics professional, we’re going to assume that you’re not pitching an ongoing series (i.e. a comic series that has no definitive end). In fact, let’s just list out what your options are and we’ll go from there.

One-Shot: A one-shot is simply that, it’s one comic book (generally between 20 and 22 pages depending on the publisher) that tells a complete story. This is probably not the venue for you as one-shots are not only very difficult to do successfully, they are also not a great jumping in point unless you’ve been commissioned to do one.

Anthologies: Anthologies are collections of short comic stories. And it's one of the best ways to get your foot in the door -- creating a solid short piece and getting it accepted to an anthology, or banding together with talented similarly motivated friends to create an anthology of your own. Short comic stories, just like prose, take a very particular set of skills, but getting a publisher to take a chance on you for one short piece (a short story could range anywhere from one page to more than a dozen) can be easier since they're risking less page space (and money) on an unknown.

Mini-Series: A mini-series is also exactly what it sounds like. It’s a small series of single issue comics – most mini-series run from 4 to 6 issues in length (so if you figure 22 pages per issue you’re looking at between 88 and 132 pages total). There are some 3-issue minis out there as well as the rare 7 or 8-issue series. Anything at 9-issues or above likely falls into a “Maxi-series” category, these are less common and generally run between 9 and 12 issues.

Ongoing: An ongoing comic is a comic that has no intended end. While it will likely end at some point, it is not designed that way. It is open-ended and continuing. Like a one-shot, this is usually not the kind of book you want to pitch unless you are established already or have been asked to pitch (in which case, why are you reading this? You already know what you're doing). An ongoing, depending on the ownership of the concept and characters, can continue on, even once the creative team leaves. For example Batman is an ongoing title.

Trade Paperback aka TPB aka Trade: Trade Paperbacks are collections of single issues that come in two forms. The first collects an arc from an ongoing run, and packages it as one volume. The second collects a completed mini-series into one volume. Most publishers these days like to release a mini-series in single issues and then, once the entire series has released, they will bundle it together into a trade and release it for a price that is slightly less than buying the issues individually. Many publishers have adopted this method of late as it not only allows them to sell the book twice – once as a monthly, and once as a trade - but it also makes it easier to get those trades onto bookstore and library shelves. To add a bit of confusion, technically a Trade Paperback can also be a Hardcover, but is usually still called a Trade (see the Batwoman hardcover edition below). Sometimes collected trades include an intro or foreward. They can also include additional material like covers, sketches, and notes from creators.

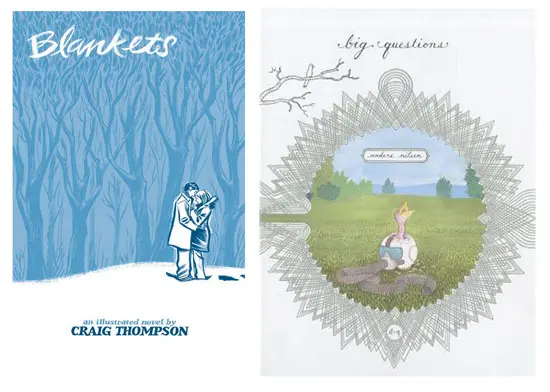

Graphic Novel: A graphic novel is considered a longer comic book and it's designed to be released as one volume, as opposed to smaller pieces. Graphic Novels are published by both comics’ publishers and by regular publishing houses with regularity. Graphic Novels are all the rage these days, and they're great things, but you should understand that they're essentially longer and complete comic books. Comics is not a bad word, though in comparison to the much more hip "graphic novel" it seems to have become one.

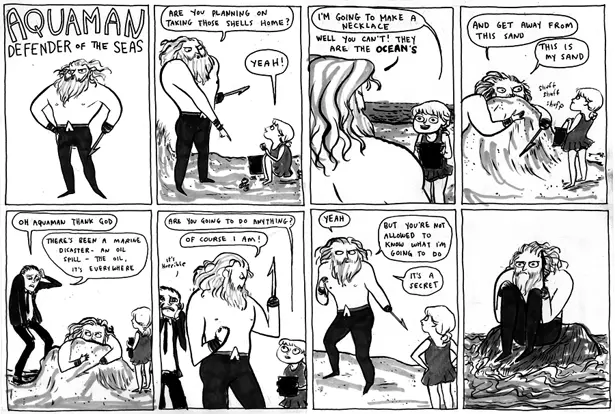

Webcomic: There are a million ways to do webcomics these days. From posting randomly on a blog or tumblr, to posting with a weekly or daily schedule, from releasing a page at a time that appears like a regular comics page and contributes to a larger story, to releasing only fully realized strips. There are many sites that host webcomics, and there are some VERY successful webcomics out there – like Kate Beaton’s Hark A Vagrant! – which is brilliant. But like any other medium, there's a lot of dreck out there, so while this avenue might eliminate the publisher for you, you’ll still have to find a way to rise to the top and get noticed, which can be difficult.

Most people writing a comic for the first time should aim for the mini-series category, which, if you do it correctly, can also overlap with Graphic Novels, giving you a little more flexibility about where you can pitch and how you can organize things. We’re going to talk more about how to actually write the comic in the next installment, but you should definitely be thinking a bit about length here. CAN you tell your story in 132 pages? If not, what’s it going to take?

After identifying how you should package your story, you should certainly identify what your genre is. Though I like to assume anyone that does any kind of writing knows the difference between medium and genre, I will admit that I’ve come across a lot of people that get confused about these two categories when it comes to comics, so I’ll break it down just in case. The medium is comics. Period. The genre can be anything from memoir or horror to superhero to western. You should definitely know, with ease, what genre your story falls under, or if it’s a hybrid of a couple genres – like a superhero comedy, etc.

There are other things to consider here as they relate to the artwork inside, tone, color, font, panel layout, etc., but we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it, further down in the process.

READ, READ, READ

If you are already a big comics fan, then you probably have already done all the reading you need to do, but if you’re fairly new to the medium then I suggest, the same way I would for prose, that the best education is reading a lot of great comics. Reading great comics can teach you all kinds of things about how much text works on a page, what kind of visuals might be a good fit for your story, and perhaps most importantly, pacing. Pacing is, for my money, one of the single greatest things that differentiate a great comic book from a good comic book. And while a lot of this is going to have to do with your artist (and picking the correct artist) down the line, you can really set the pace and tone by how you initially lay out the story in your script, thus guiding your artist to the result you’re looking for.

I would suggest reading a wide breadth of comics, so you can get a feel for everything that’s out there, but you should certainly look at books in your genre especially closely. Really examine what works and doesn’t work and why, the same way you would with prose. And while reading great books is always helpful, sometimes reading mediocre or bad books can be equally as helpful in illustrating what not to do. While I don’t urge people to waste money on bad comics, a day spent at a comic book store, reading through a lot of different books (but make sure to buy some good ones – support your local comic book store!) can teach you a lot. The library is also a great resource if you have one with a good comics & graphic novel section. Every book I mentioned above I'd recommend reading, as well as these and these!

GETTING PROFESSIONAL HELP

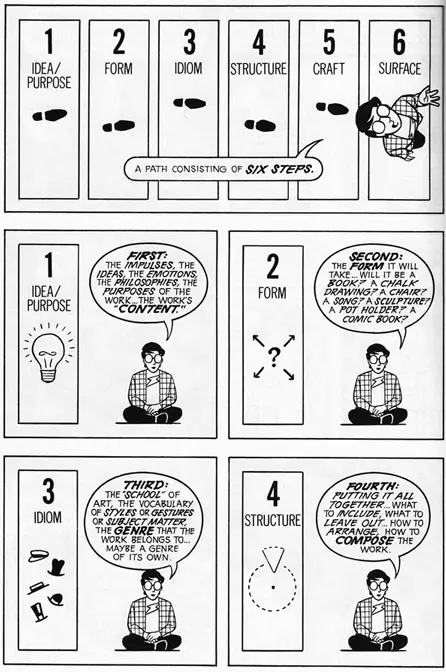

Writing comics is simply not the same as writing prose. Though it's closer to writing screenplays, it's still quite a bit different, even when it comes to formatting. So you may need some more specific (and more professional) help as you continue your research. While there is certainly a deluge of information out there, much of it bad, some of it is also very good. One book on my reading list when I was at the Savannah College of Art and Design studying comics (yes, that’s an actual major, if you’re insane, as I apparently am) was Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. It was then, and is now, one of the best books I’ve ever read about comics. It breaks down both the broad and the detailed into easy to understand pieces. It’s a book I would never part with and have referred to frequently over the years. If there is a single book you buy in your attempt to begin writing comics, this is the book.

If you’re looking for a little more guidance, I’ve found Alan Moore’s Writing For Comics is a great resource about the writing side of comics, and Jessica Abel and Matt Madden’s Mastering Comics, a sequel of sorts to their popular Drawing Words & Pictures is also good. Mastering Comics is not for the light of heart, as it’s more like a great textbook and includes activities, homework, and even extra credit.

So now you have your story idea, an idea of what format it should be, what genre you’re working in, and you’ve researched your competition and looked at some educational books…I think you’re ready to write.

So come back next month to figure out where to begin. I’ll be using an example from a mini-series pitch I put together with artist Meredith McClaren this past spring to help illustrate some of the hurdles we faced and how we solved them.

About the author

Kelly Thompson is the author of two crowdfunded self-published novels. The Girl Who Would be King (2012), was funded at over $26,000, was an Amazon Best Seller, and has been optioned by fancy Hollywood types. Her second novel, Storykiller (2014), was funded at nearly $58,000 and remains in the Top 10 most funded Kickstarter novels of all time. She also wrote and co-created the graphic novel Heart In A Box (2015) for Dark Horse Comics.

Kelly lives in Portland Oregon and writes the comics A-Force, Hawkeye, Jem & The Holograms, Misfits, and Power Rangers: Pink. She's also the writer and co-creator of Mega Princess, a creator-owned middle grade comic book series. Prior to writing comics Kelly created the column She Has No Head! for Comics Should Be Good.

She's currently managed by Susan Solomon-Shapiro of Circle of Confusion.