The only thing Hollywood loves more than making movies is turning other things into movies. We live in an age where film is fast replacing literature as the record of culture. Film reviews take up more and more printed space while book reviews dwindle. We live in an age where it’s generally accepted that if something's worth knowing, there should be a movie about it. Throughout its life, but especially in its later years, cinema has sought to prove its superiority to other art forms by consuming them and regurgitating them as “adaptations,” as if to declare that no idea was too complex, too intelligent, to be rendered into film. True lives, novels, comic books, video games and even Twitter accounts have been optioned to feed the great movie machine.

Adaptations are appetizing prospects for Hollywood execs because most of the hard work has already been done for them. An engaging story has already been written, populated with interesting, well-known characters, and it comes with a prepackaged audience. For no medium is this truer than comic books. Comic fans especially will pay to see a movie version of their beloved book no matter how bad it is, even if only to hate it more articulately. In addition to great stories and popular characters, comics also come with beautifully illustrated storyboards you can buy in any bookstore—it seems all any competent director would have to do is follow the instructions. Yet the most common criticism of comic adaptations remains “the book was better,” so much so that we accept it as a truism. There are exceptions to the rule, like 1997’s Steel, which was a terrible movie about one of DC’s lamest Z-list heroes, but the film had the added farcical charm of watching Shaquille O’Neal attempt to play a genius weapons engineer. (In every scene he has the unmistakable look of the kid who just found out there’s a test today in class However, more often than not, Hollywood has taken the greatest creations in comics and adapted them into some of the worst movies the world has ever seen.

The following is a list of brilliant comic books that did not survive their translation to the silver screen. But you shouldn't let the fact that their adaptations were bad discourage you from reading them. Just because some movie director didn’t understand what made these stories amazing doesn’t mean you won’t. Read them for yourself, because whatever interpretation your mind conjures will be infinitely more entertaining and rewarding than any number of hours spent with a glowing screen.

We’ll start with the most egregious habitual offender, the Punisher trilogy. These movies aren’t actually linked in any way, other than they’re all weak portrayals of the same character. Marvel has been struggling since 1989 to turn their most popular antihero into a movie franchise, but each attempt has just become another footnote in the history of failure. Which is sad, because each movie has one thing it did very well, but it’s never enough to keep the story from falling apart.

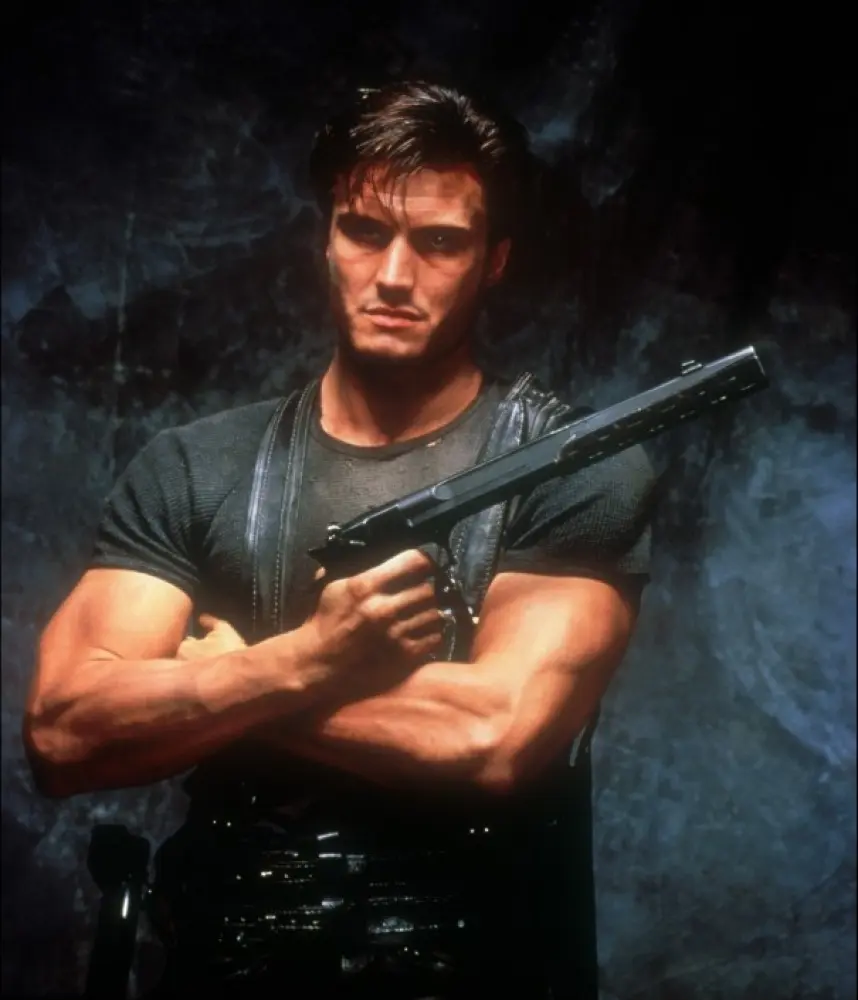

The first movie had the best Punisher, Dolph Lundgren. He sounded like Death, embodied Frank Castle’s cold rage and towered over the underworld thugs he mowed down like a dark pillar of vengeance. Unfortunately, the filmmakers stripped away everything else—his backstory, his friends, his villains and even his iconic symbol—that would make it a Punisher movie and not just another 80s revenge flick about a leather clad man shooting up bars full of gangsters and fighting ninjas that clearly have no martial arts training. It got terrible reviews, made no money and was promptly forgotten.

The first movie had the best Punisher, Dolph Lundgren. He sounded like Death, embodied Frank Castle’s cold rage and towered over the underworld thugs he mowed down like a dark pillar of vengeance. Unfortunately, the filmmakers stripped away everything else—his backstory, his friends, his villains and even his iconic symbol—that would make it a Punisher movie and not just another 80s revenge flick about a leather clad man shooting up bars full of gangsters and fighting ninjas that clearly have no martial arts training. It got terrible reviews, made no money and was promptly forgotten.

After Blade and X-Men proved that Marvel heroes could make movies that were both good and profitable, they wisely decided to reboot the Punisher, this time taking inspiration from the Garth Ennis story Welcome Back, Frank. But loyalty to the source material can be a double-edged sword—it’s just as important to cut certain scenes as it is to make sure the best ones make it in. This Punisher picture was at its best when it recreated the brutal close-quarters brawl between Castle and a giant Russian. The violence was visceral and intense, but it also struck just the right note of dark humor as Castle throws everything he can at his assailant—bottles, chairs, knives, a gun and even a hand grenade—only to be relentlessly crushed beneath the massive mercenary’s fists. Then it undermines the whole dark brooding urban avenger theme by placing him in sunny Miami, living next door to a cast of friendly neighbors. Taking the Punisher out of New York was just a cheapskate mistake, but the neighbors take up considerably more screen time than they did panels on the page, to the movie’s detriment. While they provide necessary tension relief in the comics, the neighbors are played as bad comic relief in the movie, their every scene just another tedious intermission in the punishing action you expected to see. In addition, the movie portrays Frank struggling to connect emotionally with other people which has happened in the comics NEVER. When you dedicate your life to fighting a vigilante guerilla war on crime, you’re pretty much beyond caring if other people understand or like you.

The third film, Punisher: War Zone, makes the same mistake by having Frank wracked with guilt over accidentally killing an undercover FBI agent. Then they introduce a paper thin subplot where Frank comes to care for the agent’s widow and daughter, desperately trying to imbue these hollow side characters with a significance they don’t deserve by giving us scene after scene of Frank awkwardly holding the child or staring longingly into the mother’s eyes, as if it might convince us that underneath it all the Punisher is really a nice guy. Not to mention the irony of forcing this dubious subtext into the most gory splatterflick of the three. Maybe if they ever get around to making The Punisher 4: Revengeance, they’ll take the lead from Greg Rucka’s recent revision of the series, which portrays Frank as a silent, unrelenting force of nature, writing his name across the underworld in bullets. No banter, no inner monologuing, just one man and his psychotic war against crime. He’s the answer to the age old question: What if Batman killed? That’s what the Punisher is really about—not a man on the edge, stepping back from the brink, but the man who plunges over it and never looks back.

Second most egregious amongst this assemblage of abominations is The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. The comic book is an elegant, eloquent experiment in literary fusion. Characters from classic novels get a nice shine and come together to tell new and interesting stories in the Alan Moore tradition. League samples extensively from the entire history of fiction to create a unique patchwork world, a quilt crafted so fine you can’t see a stitch between panels. The books make delightful treasure hunts for the excessively literate, determined to catalogue every reference and allusion. By assembling this “Justice League of Victorian literature” to combat a larger than life pulp fiction threat, Moore seems to suggest that perhaps the superhero isn’t a new concept at all. Perhaps they’ve been hiding in our stories all along.

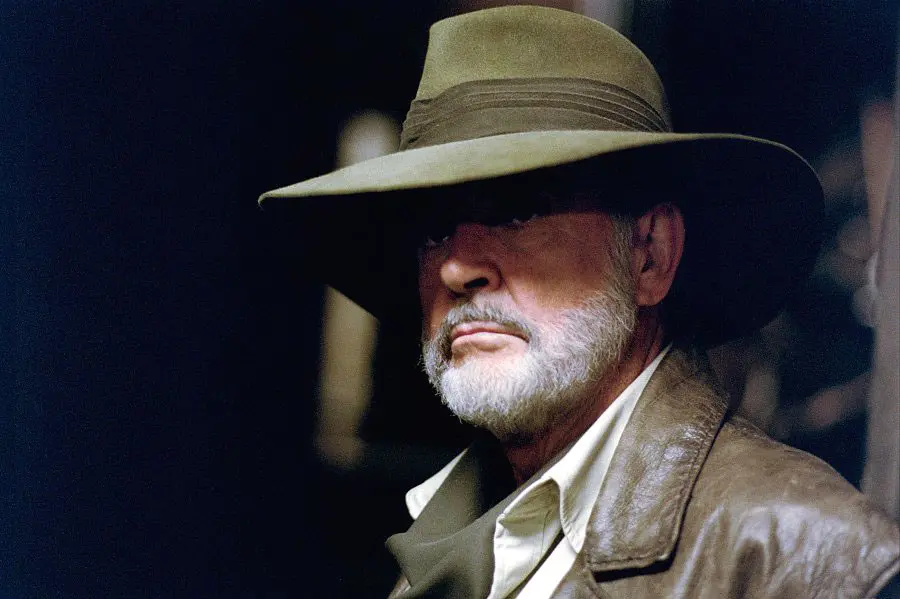

The film commits the cardinal sin of comic adaptation—it disregards its source material. The result is a movie so bad that it drove Alan Moore to scrub his name from all future adaptations of his work. Script surgeons picked apart the stitches, rearranged the patches and added a few of their own to create their own Frankenstein quilt, a monstrous distortion of its original inspiration. Mina Harker is no longer the leader and moral center of the League and made into a vampire, even though in Stoker’s novel she returned to normal after the death of Dracula. Instead of a determined, strong-willed woman who takes charge in a man’s world she is reduced to a super powered moll waiting to be let off the leash. I have no doubt the writers thought they compromised by giving her more fight scenes. She can’t be in charge because Allan Quartermain is played by Sean Connery. His character gets upgraded from the opium addict he was in the book to just mildly depressed and nostalgic for the old days. The Quartermain of the comics had to be dragged along and bullied by the not to be trifled with Harker into serving his country once again. He was unreliable, damaged, and very much not the intrepid adventurer he once was. Connery gives a similar getting old speech, but as soon as the bullets start flying he is 007 again. He makes every shot and bests several physically formidable toughs in fisticuffs. He keeps saying he’s too old for this shit, but he also keeps doing it—gunfights, explosions, jumping from moving cars—there are men half his age that can’t do all that. These kinds of contradictions continue to undermine the motivations of every character in the movie. Captain Nemo declares that he doesn’t use guns (which isn’t true in the books), yet built an underwater war machine crewed by men armed with electric rifles of his design. Ruthless murderer Edward Hyde waxes poetic about how he loves the sweet taste of London’s sorrow, but then immediately agrees to serve his country without argument and proceeds to follow orders like a good soldier, causing no trouble for the rest of the film. It’s the kind of movie where the bad guy tells one of the heroes his only weakness and then looks stunned when it’s turned against him in the final act. In a movie that features Victorian-era machine guns, steampunk tanks, invisible men and vampires, the only thing that's beyond belief is the behavior of the characters. LXG might have been a decent action movie in a pre-Matrix era, but in 2003 it was just a large, sloppy, jump cut mess.

The film commits the cardinal sin of comic adaptation—it disregards its source material. The result is a movie so bad that it drove Alan Moore to scrub his name from all future adaptations of his work. Script surgeons picked apart the stitches, rearranged the patches and added a few of their own to create their own Frankenstein quilt, a monstrous distortion of its original inspiration. Mina Harker is no longer the leader and moral center of the League and made into a vampire, even though in Stoker’s novel she returned to normal after the death of Dracula. Instead of a determined, strong-willed woman who takes charge in a man’s world she is reduced to a super powered moll waiting to be let off the leash. I have no doubt the writers thought they compromised by giving her more fight scenes. She can’t be in charge because Allan Quartermain is played by Sean Connery. His character gets upgraded from the opium addict he was in the book to just mildly depressed and nostalgic for the old days. The Quartermain of the comics had to be dragged along and bullied by the not to be trifled with Harker into serving his country once again. He was unreliable, damaged, and very much not the intrepid adventurer he once was. Connery gives a similar getting old speech, but as soon as the bullets start flying he is 007 again. He makes every shot and bests several physically formidable toughs in fisticuffs. He keeps saying he’s too old for this shit, but he also keeps doing it—gunfights, explosions, jumping from moving cars—there are men half his age that can’t do all that. These kinds of contradictions continue to undermine the motivations of every character in the movie. Captain Nemo declares that he doesn’t use guns (which isn’t true in the books), yet built an underwater war machine crewed by men armed with electric rifles of his design. Ruthless murderer Edward Hyde waxes poetic about how he loves the sweet taste of London’s sorrow, but then immediately agrees to serve his country without argument and proceeds to follow orders like a good soldier, causing no trouble for the rest of the film. It’s the kind of movie where the bad guy tells one of the heroes his only weakness and then looks stunned when it’s turned against him in the final act. In a movie that features Victorian-era machine guns, steampunk tanks, invisible men and vampires, the only thing that's beyond belief is the behavior of the characters. LXG might have been a decent action movie in a pre-Matrix era, but in 2003 it was just a large, sloppy, jump cut mess.

Some adaptations can be overwhelmed by a plethora of source material. Judge Dredd is the most famous and longest-running comic book hero in Britain. The character was created as a cynical neo-fascist nightmare of what disciples of the Dirty Harry school of police work might look like in a distant dystopian future. After the nuclear war of 2070, the cities were flooded with survivors and society collapsed into chaos. To restore order, a new justice system was established—judges are the ultimate authority figures, with the power to enforce law on the street, as well as try, convict and occasionally execute criminals on site. While the comics become distressingly more relevant with each passing year, Hollywood stripped away the political satire to produce a formulaic action film whose biggest science fiction conceit is that Armand Assante somehow poses a physical threat to Sylvester Stallone. Not only did it discard over twenty years of publication history by having Dredd remove his helmet in the first twenty minutes, never to put it back on, but then it tried to cram in so much backstory and mythology that it could do justice to none of it, all in some futile attempt to prove its loyalty to the source. Mega-City One, one of the richest storytelling settings in all science fiction, is introduced in a breathtaking flyover at the beginning, and then never explored. The narrator informs us that the judges were formed to control insane outbreaks of violence, but we only see Dredd bullying petty criminals—he blows up a car that has too many unpaid parking tickets, and he sentences a man to five years hard labor for accidentally defacing public property as he fled for his life. When Dredd is framed, exiled, betrayed, and then finally learns the ultimate secret behind his existence, we don’t care. Movie Dredd hasn’t done anything heroic to earn our sympathy. If anything he’s a superhero for police brutality. In the comics, the judges are a harsh solution for an equally harsh world and when Dredd makes a tough decision the reader is forced to question how they could have really done any better in the same situation. The movie asks us to cheer for a totalitarian stormtrooper as he cows the unclean masses into submission. The only reason this movie was even made was because in the wake of Demolition Man, Stallone playing a cop in the future seemed like easy money (that being said, why nobody has made the obvious crossover Judge Dredd vs. Demolition Man is beyond me). While the film is a justly forgotten relic of its time, the comics remain a glorious cult sci-fi treasure well worth a read.

Some adaptations can be overwhelmed by a plethora of source material. Judge Dredd is the most famous and longest-running comic book hero in Britain. The character was created as a cynical neo-fascist nightmare of what disciples of the Dirty Harry school of police work might look like in a distant dystopian future. After the nuclear war of 2070, the cities were flooded with survivors and society collapsed into chaos. To restore order, a new justice system was established—judges are the ultimate authority figures, with the power to enforce law on the street, as well as try, convict and occasionally execute criminals on site. While the comics become distressingly more relevant with each passing year, Hollywood stripped away the political satire to produce a formulaic action film whose biggest science fiction conceit is that Armand Assante somehow poses a physical threat to Sylvester Stallone. Not only did it discard over twenty years of publication history by having Dredd remove his helmet in the first twenty minutes, never to put it back on, but then it tried to cram in so much backstory and mythology that it could do justice to none of it, all in some futile attempt to prove its loyalty to the source. Mega-City One, one of the richest storytelling settings in all science fiction, is introduced in a breathtaking flyover at the beginning, and then never explored. The narrator informs us that the judges were formed to control insane outbreaks of violence, but we only see Dredd bullying petty criminals—he blows up a car that has too many unpaid parking tickets, and he sentences a man to five years hard labor for accidentally defacing public property as he fled for his life. When Dredd is framed, exiled, betrayed, and then finally learns the ultimate secret behind his existence, we don’t care. Movie Dredd hasn’t done anything heroic to earn our sympathy. If anything he’s a superhero for police brutality. In the comics, the judges are a harsh solution for an equally harsh world and when Dredd makes a tough decision the reader is forced to question how they could have really done any better in the same situation. The movie asks us to cheer for a totalitarian stormtrooper as he cows the unclean masses into submission. The only reason this movie was even made was because in the wake of Demolition Man, Stallone playing a cop in the future seemed like easy money (that being said, why nobody has made the obvious crossover Judge Dredd vs. Demolition Man is beyond me). While the film is a justly forgotten relic of its time, the comics remain a glorious cult sci-fi treasure well worth a read.

Dredd might not have been presented at his best, but few comic characters have suffered a more gross misinterpretation than John Constantine. Originally created by Alan Moore to serve as an occult advisor to Swamp Thing, he was so popular with fans that he eventually got his own series, Hellblazer, under the Vertigo imprint, which is its longest running continuous title to date. Constantine was unlike other occult figures in comics—he did not come from some ancient land or mystical otherworld, he had not inherited a curse or item of power. He was just some witty bloke from Liverpool who knew a lot about magic, and when he talked he always sounded like the smartest guy in the room, so of course the obvious choice to play him was… Keanu Reeves. The movie version of Constantine seems to think he is an underworld superhero, exorcizing evil spirits and charging into battle against demon hordes armed with a golden crucifix shotgun. In the books, he is never quite so bold. He’s a magician, not a wizard, and not a particularly powerful one at that. Constantine rarely uses magic because he knows it comes with a high cost and is hard to control. The number of magic tricks employed in the movie probably would have filled a year’s worth of  back issues. In the comics, Constantine is more of a magic hustler, relying on his cleverness and occult knowledge to manipulate and trick the various paranormal entities he encounters. While in the movie Constantine struggles to buy his way into Heaven, in the comics he conned his way out of Hell by selling his soul to two different demon warlords. Keanu’s Constantine is a victim of his connection to the spiritual realm, doomed to be kicked about by the Powers That Be. The Constantine of the comics may not be powerful, but he has agency and is often able to take advantage of a game that is heavily weighted against him. Both versions present an occult underdog, but the comics gives a guy that can actually win, so we’re more inclined to root for him and dismiss Keanu’s sweaty intensity with a shake of the head. If you want to delve into one of the most intricate and well-developed character studies in the history of comics, just pick up the first Hellblazer collection you can find.

back issues. In the comics, Constantine is more of a magic hustler, relying on his cleverness and occult knowledge to manipulate and trick the various paranormal entities he encounters. While in the movie Constantine struggles to buy his way into Heaven, in the comics he conned his way out of Hell by selling his soul to two different demon warlords. Keanu’s Constantine is a victim of his connection to the spiritual realm, doomed to be kicked about by the Powers That Be. The Constantine of the comics may not be powerful, but he has agency and is often able to take advantage of a game that is heavily weighted against him. Both versions present an occult underdog, but the comics gives a guy that can actually win, so we’re more inclined to root for him and dismiss Keanu’s sweaty intensity with a shake of the head. If you want to delve into one of the most intricate and well-developed character studies in the history of comics, just pick up the first Hellblazer collection you can find.

The moral of the story is, don’t let a terrible movie convince you that it has any reflection on its source material. Comic to film adaptation remains an inexact science fraught with peril, but there is hope. For every ten times Hollywood fails, there are one or two films, like The Dark Knight or Persepolis, that remind us that it’s not impossible to make a good comic book movie. Perhaps with practice, they might even get better.

About the author

BH Shepherd is a writer and a DJ from Texas. He graduated from Skidmore College in 2005 with degrees in English and Demonology after writing a thesis about Doctor Doom. A hardcore sci-fi geek, noir junkie and comic book prophet, BH Shepherd has spent a lot of time studying things that don’t exist. He currently resides in Austin, where he is working on The Greatest Novel Ever.