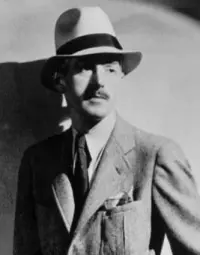

Header and author photo via Wikipedia

Dashiell Hammett, the hard-drinking ex-detective credited with helping found and popularize the crime genre known as “hardboiled,” would likely be celebrating his 126th birthday this May 27 with a shot if he was still around. The author perhaps best known for penning The Maltese Falcon didn’t just write about adventure, he also lived it; serving in both World Wars and as a Pinkerton man, he was also a romantic partner of the playwright Lillian Hellman, and a civil rights activist who was jailed for his communist affiliations.

As a writer, Hammett’s unpretentious style underscored a complex life and helped define the literary landscape of the 1930s and beyond. His heroes were salt-of-the-earth types, and Hammett acknowledged that his entry into the writer’s life was greatly aided by the fact that he didn’t know enough about it to be truly daunted. “What I try to do is write a story about a detective rather than a detective story,” Hammett once said during a 1929 interview.

Keeping the reader fooled until the last, possible moment is a good trick and I usually try to play it, but I can't attach more than secondary importance to it. The puzzle isn't so interesting to me as the behavior of the detective attacking it.

Hammett was born on a tobacco farm in Maryland in 1894. His father pulled him out of school at the age of 13, and he began his eclectic career working numerous odd jobs such as a messenger for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, a newspaper boy, and respectively for an advertising and stockbroker’s office, the latter from which he was “amiably” fired. He joined the Pinkerton Detective Agency at the age of 20 in 1915, where he would work until 1922. It was this job that provided the fuel for much of his later fiction, generating stories that would shift subtly in their re-tellings over the years, such as the time he caught a man who stole a Ferris wheel.

"I knew a man who once stole a Ferris wheel," Hammett recounted in the same 1929 interview with The Brooklyn Eagle Magazine. "And then there was the man I shadowed out into the country for a walk one Sunday afternoon who lost his bearings completely and I had to direct him back to the city. And I once knew a detective who attempted to disguise himself so thoroughly that the first policeman he met took him under arrest. And then there was the man I knew, and still know, who will forge the impressions of any set of fingers in the world for only fifty dollars...”

He runs out of time in this interview, but not before offering shades of other characters encountered during his time as an “op,” such as the chief of police of a southern city who gave him a description of a man down to the mole on his neck, but neglected to mention that he had only one arm, or the forger who left his wife because she had learned to smoke cigarettes while he was serving a term in prison. Sleuthing, he confided, was his favorite of the myriad professions he’d sampled.

According to the Paris Review, Hammett claimed to have been involved in several high-profile cases, including a mission to break up the Anaconda Copper miners’ strike in Butte, Montana, as well as an investigation into the theft of gold aboard the SS Sonoma among other anecdotes. Later biographers would view these tales with a skeptical eye, but they do little to detract from the image of Hammett as a kind of underdog, everyman’s hero.

According to the Paris Review, Hammett claimed to have been involved in several high-profile cases, including a mission to break up the Anaconda Copper miners’ strike in Butte, Montana, as well as an investigation into the theft of gold aboard the SS Sonoma among other anecdotes. Later biographers would view these tales with a skeptical eye, but they do little to detract from the image of Hammett as a kind of underdog, everyman’s hero.

His exit from the Pinkertons and into the world of writing appears to have been motivated by his inconsistent health. Hammett enlisted with the Army in 1918 before either contracting or exaggerating latent tuberculosis during World War I, and the aftereffects would dog him through the years. So he turned to fiction. In his own words, Hammett stated he had no prior writing experience except that of writing letters and daily reports for headquarters as a Pinkerton. Despite his lack of experience as an author, his words quickly found their mark with audiences who appreciated his sharp, direct tone, and who were intrigued by his professional background with the Pinkertons. Hammett would produce over 80 stories throughout the course of his life, but his streak ground to a halt after The Thin Man was published. Much like Nick Charles, hero of The Thin Man, he “devoted himself to an intensive study of the liquor problem from the consumer’s standpoint.”

Hammett’s later life took a surprising turn in his altercations with the infamous Red Scare era politician Joseph R. McCarthy, whom he was called to testify before (he invoked the Fifth Amendment when asked if he had ever been a member of the communist party). The removal of Hammett’s works was demanded from overseas libraries in 1953 after being listed with fifteen other authors as “undesirable.” After enlisting and serving in World War II at the tender age of 48, Hammett began to dedicate his time to more left-wing causes. A 1961 obituary for the author in the New York Times states that he was trustee of the bail fund of the Civil Rights Congress, an “organization that had been designated by the Attorney General as a communist front.” Hammett wound up serving six months in prison in Kentucky when four Communist leaders jumped bail, and he refused to name other contributors to the bail fund.

Hammett would live out the end of his days in New York City as the house guest of Ms. Hellman, passing away due to lung cancer in 1961. An extract from “So I Shot Him,” a Hammett story found in a Texas archive, seems to summarize the author’s approach towards life: "’I wouldn't have a dog that was cat-shy,’ he wound up. ‘What good is a dog, or a man, that's afraid of things?’"

Buy The Thin Man from Bookshop or Amazon

Buy The Maltese Falcon from Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Leah Dearborn is a Boston-based writer with a bachelor’s degree in journalism and a master’s degree in international relations from UMass Boston. She started writing for LitReactor in 2013 while paying her way through journalism school and hopping between bookstore jobs (R.I.P. Borders). In the years since, she’s written articles about everything from colonial poisoning plots to city council plans for using owls as pest control. If it’s a little strange, she’s probably interested.