In my last post, we discussed what goes into a horror story and how to write one that will scare readers. In this post, let’s talk about something a bit more niche: dark poetry. This subgenre has increased in popularity over the years, but what is it and how do you write it?

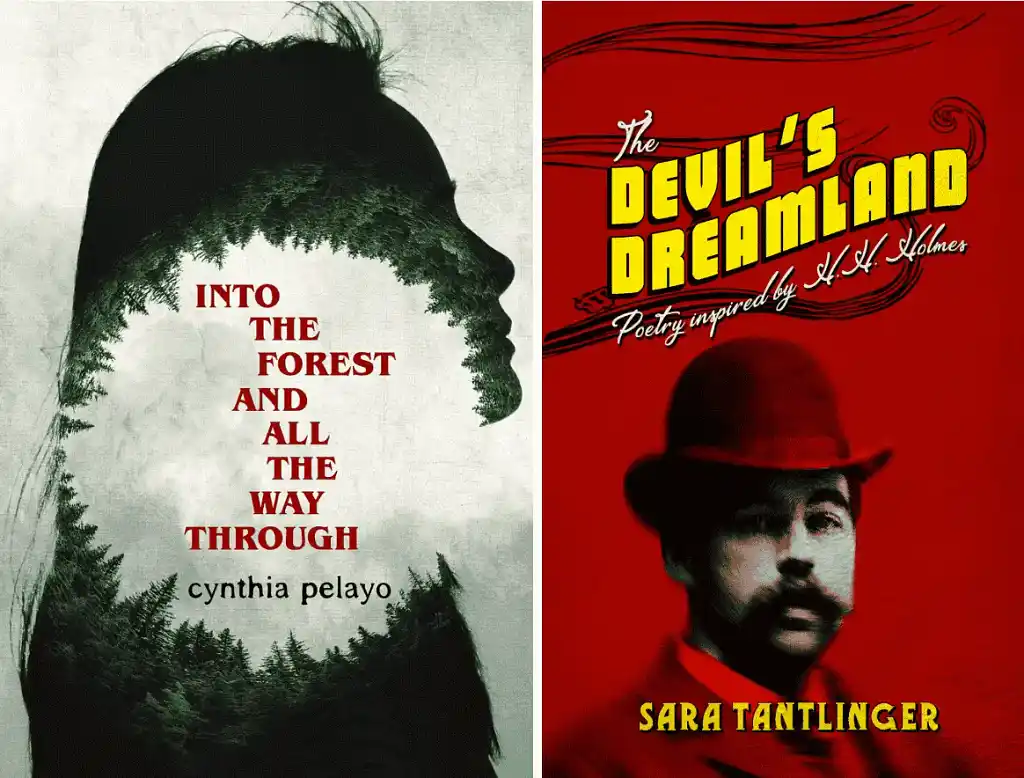

As the author of a Bram Stoker-nominated poetry collection (Into the Forest and All the Way Through), I’m here to give you the lowdown on this unusual form of poetry: its history, its core elements, and how to approach writing a dark poem of your own.

What is dark poetry?

Dark poetry refers to any poetry that includes “dark” elements. This type of poetry can fall under various genres such as mystery, thriller, crime, and of course, horror.

While much of modern poetry is autobiographical and therefore primarily qualifies as creative nonfiction, dark poetry is perhaps more evenly split between fiction and nonfiction. One might write a purely speculative dark poem, or take a more realistic approach to the form.

In my own collection, I’ve split the difference — Into the Forest is inspired by real-life events, but I’ve put my own imaginative, somewhat speculative spin on them (more on that later).

The evolution of dark poetry

So where did dark poetry come from? In truth, it’s existed for centuries in one form or another.

Consider some of the earliest poetry in the canon — particularly the epic poems adapted from oral storytelling. Many of these works heavily featured elements of the supernatural, suffering, and death. For example:

- The Epic of Gilgamesh (the oldest longform poem in history) features gods and demons;

- Beowulf is about monsters, dark magic, violence, and death;

- The Iliad deals with war and profound loss;

- And so on.

While it’s true these works don’t bear much similarity to the dark poetry of today — which tend to play on more modern fears — they formed a solid foundation for later poets to iterate upon. Indeed, dark poetry as we’d recognize it today came into its own in the early 19th century, with the rise of the Romantic movement.

Dark poetry examples

John Keats was a central figure in the Romantic literary movement, and many of his works have since become famous as pieces of dark poetry.

One of my favorites, a poem titled “After dark vapors have oppress’d our plains,” ends with the words:

The gradual sand that through an hour-glass runs –

A woodland rivulet – a Poet’s death

Keats was certainly inventive, evocative, and sometimes morbid. In “Ode to a Nightingale”, one of his most famous poems, he writes:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Many will also know the name of Percy Bysshe Shelley — husband of Mary Shelley and close friend to Lord Byron. Besides keeping iconic company, Shelley was an accomplished poet himself.

In “Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude”, he writes:

When night makes a weird sound of its own stillness,

Like an inspired and desperate alchemist

Staking his very life on some dark hope

Then there’s the Gothic poet whom many of us associate with the rich literary darkness of yore: Edgar Allan Poe. Though perhaps best known for channeling a crazed murderer in the short story The Tell-Tale Heart, many of his “dark” poems offer just the right balance of sweetness, melancholy, and despair.

For example, in “The Happiest Day, The Happiest Hour” Poe writes:

The happiest day - the happiest hour

My seared and blighted heart hath known,

The highest hope of pride and power,

I feel hath flown.Of power! said I? Yes! such I ween

But they have vanished long, alas!

The visions of my youth have been

But let them pass.

Indeed, while some dark poetry is truly dark, much of it takes on a sad or wistful tone. The Romanticists and Poe nurtured these elements, but they continue to prevail in dark poetry today.

I think this is because many poets are introspective and empathetic, always observing the human condition. However, the human condition is not always a happy one… hence why dark poetry has taken off as a form of cathartic self-expression in recent years.

If you haven’t read much dark poetry yourself beyond Keats and Shelley (if even them), I’d highly recommend checking out some contemporary poets as well. A few of my own favorites — many of whom have also contributed here on Litreactor — include Linda Addison, Stephanie Wytovich, John Urbancik, Maxwell Ian Gold, Mike Arnzen, Sara Tantlinger, Sumiko Saulson, Jessica McHugh, and more.

The elements of dark poetry

Like all poetry, dark poetry is a fairly broad category which can encompass many things. There’s no one “right” subject matter or poetic structure (e.g. a sonnet or an ode) that you must use — as I’ve touched on already, if it has any kind of darkness to it, it can be called dark poetry.

That said, there are a few specific things to consider when attempting this form for the first time. We’ve already covered some of the tonal possibilities of dark poetry in the examples above; now let’s break down its other key elements.

1. The catalyst: an issue you care about

According to the poet F.J. Bergmann, great poetry requires three elements. The first of these is its prompt/stimulus, which I would define as the catalyst of a poem.

Basically, what set this poem in motion? Poets are frequently inspired by their own lives, but many poets I know are equally inspired by other people and other art, as well as the news and current events.

Needless to say, when it comes to dark poetry, your catalyst may not be a positive one; it may even come from (or evoke) some degree of trauma.

For example, with my collection Into the Forest and All the Way Through, I wanted to give a voice to the many missing and murdered women in the United States. I was frustrated by the proliferation of true crime content around these cases, and I wanted to remind readers of the toll taken — on these women, their families, and ultimately society — when we treat misogyny and murder as fodder for our entertainment.

I definitely think that having a strong catalyst for a poem makes all the difference between poetry that’s “impactful” and poetry that is not. I believe this catalyst is what holds the entire poem together; without an adequate impetus for your writing, something you’re truly passionate about, your poem will inevitably collapse.

2. The content: a narrative that makes others care

The next key element of poetry that F.J. Bergmann names is its content. This one should be self-explanatory — it’s the narrative of your poem that stems from that initial catalyst.

Another example, from one of my aforementioned favorite poets: Sara Tantlinger’s The Devil’s Dreamland is based on the life of H.H. Holmes, often referred to as America’s first serial killer.

In these poems, Tantlinger investigates Holmes, his victims, and the methods by which he mutilated and murdered them. It’s a difficult read, yet also undeniably propulsive — and, similar to Into the Forest, this collection aims to give a voice and wider recognition to victims who would never have reached the 21st century otherwise.

What’s interesting about Tantlinger’s content — and which may be useful for new poets to study — is how she varies the syntax and presentation of each poem to create varying effects, yet it all still comes together in a cohesive collection.

Like Tantlinger, you can use this white space to intentionally keep things ambiguous or leave “room to ruminate” if you like. Indeed, when it comes to dark poetry narratives, what’s not said is often just as powerful (if not more so) than what’s made explicit.

3. The technique: a structure that serves your message

We can segue naturally from white space into Bergmann’s third and final “key element” of poetry: your technique. This relates to your structure, word choice, and any granular stylistic tools you’re using in the poem.

Again, there’s no single technique which is “better” or “worse” for dark poetry — so just write however comes naturally to you. If you prefer a certain rhythm and rhyme to your poetry, you can go with an established poetic structure; but if you think your message will be better served by having no constraints whatsoever, then you don’t have to think about rhyme schemes at all.

Here’s a quick refresher on some of the most commonly used structures in dark poetry (though again, feel free to use whatever works for you):

📕 Sonnet

A sonnet is a classical style of poetry (you might know it from Shakespeare) with fourteen lines and a clear rhyming scheme.

A sonnet typically covers just one topic, but hits it hard — so if you’re looking to make a strong impression in relatively few lines, a sonnet could be the structure for you.

📒 Villanelle

The villanelle originated from Italian song composition, and is known for repeating ABA lines — that is, Line 1 rhymes with Line 3 (both being “A”) while Line 2 does not (being “B”).

For example, Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song” is a villanelle:

A: I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

B: I lift my lids and all is born again.

A: (I think I made you up inside my head.)

📘 Free verse

What it says on the tin: no identifiable rhyme or rhythm, just lines of poetry arranged however you like.

As a free verse poet myself, I would strongly recommend this technique for those who are just starting off. Many poets enjoy writing free verse because it gives them total flexibility with tone, range, and formatting, and it’s probably the easiest form to dive into for these reasons.

Of course, you’ll still need to consider your catalyst and content with free verse — and edit your poetry to convey your precise intention — but with any luck, the freedom of this form will help you go beyond your previous boundaries to create something truly breathtaking.

How to write dark poetry

We’ve covered the definition, history, and elements of dark poetry. Now I’ll take you through the steps of how to write it, based on my own writing process!

Obviously these steps will incorporate what we’ve talked about above, but you should be able to execute them even if you’ve jumped straight to this section. Without further ado, here’s how to write dark poetry in four steps.

1. Find a darkness that speaks to you

Great poetry has always touched on heavy subject matter, and that’s never been truer than it is today. Pain, grief, death, and war are just a few subjects that I’ve seen covered in recent dark poetry; perhaps one of these subjects speaks to you as well.

If you want to take a leaf out of my book (somewhat literally), I’d suggest thinking of a specific issue about which you feel passionate (your catalyst, in other words). Consider recent and historical developments around things like women’s rights, LGBTQIA+ rights, racial discrimination, etc.

And think about how each issue connects to your life. Does it affect you personally, or someone you know? Is it something you find yourself thinking about a lot? Sometimes the best reason to write poetry (especially dark poetry) is just to get something out of your head and onto the page.

In that vein, the first step here is to pick your subject — then just freewrite a bit. Don’t be afraid to dive deep into the pain, suffering, and even genuine terror around your subject matter.

It might be hard to get things down at first, but remember that what you’re writing is important — so try not to flinch away.

2. Conjure striking visuals

Now it’s time to get into writing your poetry, and a major part of that is visuals.

Think about which visuals you might associate with the subject and theme(s) you wish to tackle. These may be very literal or more metaphorical; the level of forthrightness is up to you.

A few examples to give you an idea of what I’m talking about:

- Death – think of caskets, mourners dressed in black, a rattling hearse, old gravestones, etc.

- Loneliness – images of isolation like empty rooms, barren landscapes, unanswered messages, etc.

- Depression – black nightfall, drowning in a deep ocean, getting lost in a fog, etc.

- War and violence – to be more concrete, images of bloodied bodies and mourning families; or, to be more figurative, describe any sort of conflict, large or small (this poem by Rudy Francisco comes to mind).

Consider brainstorming a list of these images before you actually start writing your poem, or starting with a simple central image and then branching out from there.

Both of these are easy yet effective ways to get into the “flow” of writing dark poetry; from there, your structure should begin to take shape.

3. Go deeper with philosophical questions

In addition to “only” thinking about the surface-level darkness of your subject, you’ll also want to think about the deeper philosophical questions behind it.

For example, if your subject of choice is death, you may want to consider not only the question of why death is so hard to face, but also:

- What is the meaning of life — that is, death signifies the loss of what, exactly?

- Why do people handle death differently, and is there any “good” way to think about it?

- Where do we go after we die; what does it mean if the answer is “nowhere”?

To be fair, you wouldn’t need to address all these questions in detail (especially if you’d chosen a relatively short form like a sonnet). But you can still imply your thoughts on one or two of them — perhaps with a figurative image, as we’ve discussed.

I personally like to delve into philosophical questions about how society functions, what its failures are, which members of society are most valued, and why that might be. Again, you don’t need to put a social justice issue at the heart of your poem… but if you chose to do so, as I have, then you may want to address similar questions.

4. Refine your poem’s atmosphere and tone

Finally, it’s time to review those images and word choices you came up with, and decide what to keep and what to cut. Focus on putting forth just a couple of powerful images that accomplish what you need them to.

For example, you might have “set” your poem in a barren landscape by describing the leafless trees, the cracked, dry ground, and low-hanging clouds in a grey sky. This would create an atmosphere of loneliness and despair — but not anything more extreme than that.

But if you wanted your poem to be more horrifying than gloomy, you might instead zoom in on, say, a decomposing human body. Rotting flesh, crawling maggots, gaping eye sockets… a very different effect indeed!

Again, just review your images and syntax to ensure these elements are successful, and not conjuring a tone that’s either “hard” or too “soft” based on your subject matter.

Finally, try reading your poem out loud to see if anything sounds awkward, stilted, or perhaps more silly than scary. Even just altering a few words can make a huge difference to the overall effect of your poem — so take your time to make it perfect, and you’ll have a dark poem you’ll be proud to (potentially) publish. Best of luck!

About the author

Cynthia Pelayo is a Bram Stoker Award winning and International Latino Book Award winning author and poet. Pelayo writes fairy tales that blend genre and explore concepts of grief, mourning, and cycles of violence. She is the author of Loteria, Santa Muerte, The Missing, Poems of My Night, short stories, poems, and more.