When one associates with excessively literate company, it is quite impossible to avoid the game of canon bingo. Titles of books are invoked and those assembled either declare they have read it, or confess they haven’t yet. The only prize in this contest is the smug satisfaction of being the most well-read person in a room full of well-read people. These are special books, tomes that the enigmatic cabal known only as THEY have decreed you must read, classic works of genius so time-honored and true that they made it on the only list that really matters in literature: canon.

As comics continue to accrue cultural currency, their occurrence in canonical conversations can only increase. Academic studies of graphic storytelling proliferate in centers of higher learning while publications of note have bestowed the classification of literature on certain exceptional titles. Though the medium is young, its offerings are vast and varied, which can be discouraging to the uninitiated. Establishing a canon of essential titles not only provides a road map for newcomers, but also builds a frame of reference for furthering the debates of the medium’s more fervent disciples.

To that interest, I have compiled a list. It is neither comprehensive nor definitive. While I cannot presume to speak for THEY, I have spent the better part of my life reading and talking about comics. These graphic novels are typically regarded as unimpeachable pinnacles of the form. Of course there are always those that would disagree, but there is no denying that these books are frequently the subject of both casual conversation and deconstructive discourse. Any discussion of comics, once all participants have exhausted their enthusiasm for their favorite heroes, will inevitably visit one if not all five of these books. Whether you love them or hate them, being familiar with these volumes will ease your entry into the realm of illustrated adventures.

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale is the book that finally convinced everybody that graphic novels could be serious. It is one of those rare graphic novels so brilliant as to break into the Canon (capital C) of respected literature. Revered comic scribe Alan Moore (whose own work is featured later on this list) called Spiegelman “the single most important comic creator working within the field.” This haunting chronicle of life in Poland during the Second World War recasts America’s favorite tragedy with cats as Nazis and mice playing Jews, and somehow that only makes it sadder. Art Spiegelman took talking animals, a plot device usually reserved for children’s fiction, and used it to tell one of the most powerful Holocaust stories ever put to paper. Though it wasn’t the first comic book to make the New York Times Bestseller list or to win critical acclaim and literary accolades, it is still the only one to ever win a Pulitzer. It has been the subject of academic study, and is one of the few comic books taught in high schools across the country. If you never read comics as a kid, then Maus was likely your first encounter with graphic storytelling that didn’t feature Mickey Mouse or Grover. I can’t imagine how rough that transition would be—how many mothers must have brought this book home to their children, thinking it just another innocuous illustrated adventure about talking mice. Be warned, this book is not gentle, but it is a must read, and the one comic book that almost everybody has read.

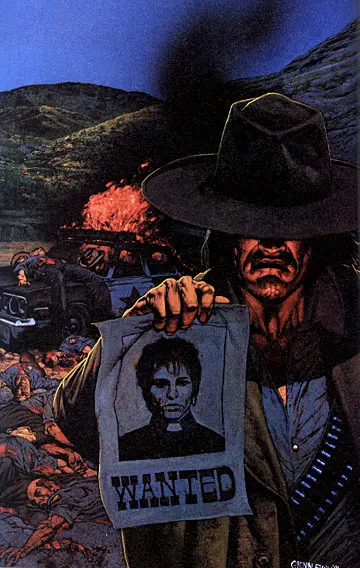

Preacher, on the other hand, is gleefully brutal and bizarre. The story follows Jesse Custer, a small-town Texas preacher who is suddenly empowered with the Word of God—when he speaks, people are compelled to obey him. After interrogating an angel, Custer learns that God is absent, having given up on creation. Together with his gun-toting girlfriend Tulip and his new best pal Cassidy the Irish Vampire, he sets out on a quest to hunt down the Lord and make him answer to Creation. Along the way he is pursued by the Grail, a clandestine brotherhood dedicated to protecting the bloodline of Christ, as well as the Saint of Killers, literally the patron saint of murderers. This taboo-smasher from Vertigo went everywhere things like the Comics Code and common decency said one should not go, and did so with such relentless determination that it almost seemed like writer Garth Ennis was on a mission to cross as many lines as he could find. Aside from the overt religious controversy of making God the main antagonist, the book deals with everything from incest and bestiality to schizophrenia and suicide. On his journey Jesse meets an assortment of surreal characters: a journalist who covers his own activities as a serial killer, the unluckiest cop in the world, voodoo priests, a pair of sexual private investigators from Scotland (don’t ask), a lawyer with a Nazi fetish, and a porn star traveling to Houston to look for work after an unfortunate electric dildo accident got him blacklisted, just to name a few. Despite being packed to the brim with acts most upright citizens would call unspeakable, it never compromises the story for shock value. Jesse Custer and his motley crew lead you through this strange, grotesque world with just enough dark humor to keep you from closing the book in despair. The dialogue is brilliantly written, with such a flair for ostentatious Southern swearing you’d never believe it was penned by an Irishman. By the end of the book the characters feel like old friends and you are sad to bid them farewell, and their backstories are so fascinating that at times you will forget to care about whether or not God ever gets what’s coming to him. An epic modern myth with plenty of Wild West style, Preacher is a singularly profound feat of storytelling that belongs on the shelf of any half-serious comic book academic.

Preacher, on the other hand, is gleefully brutal and bizarre. The story follows Jesse Custer, a small-town Texas preacher who is suddenly empowered with the Word of God—when he speaks, people are compelled to obey him. After interrogating an angel, Custer learns that God is absent, having given up on creation. Together with his gun-toting girlfriend Tulip and his new best pal Cassidy the Irish Vampire, he sets out on a quest to hunt down the Lord and make him answer to Creation. Along the way he is pursued by the Grail, a clandestine brotherhood dedicated to protecting the bloodline of Christ, as well as the Saint of Killers, literally the patron saint of murderers. This taboo-smasher from Vertigo went everywhere things like the Comics Code and common decency said one should not go, and did so with such relentless determination that it almost seemed like writer Garth Ennis was on a mission to cross as many lines as he could find. Aside from the overt religious controversy of making God the main antagonist, the book deals with everything from incest and bestiality to schizophrenia and suicide. On his journey Jesse meets an assortment of surreal characters: a journalist who covers his own activities as a serial killer, the unluckiest cop in the world, voodoo priests, a pair of sexual private investigators from Scotland (don’t ask), a lawyer with a Nazi fetish, and a porn star traveling to Houston to look for work after an unfortunate electric dildo accident got him blacklisted, just to name a few. Despite being packed to the brim with acts most upright citizens would call unspeakable, it never compromises the story for shock value. Jesse Custer and his motley crew lead you through this strange, grotesque world with just enough dark humor to keep you from closing the book in despair. The dialogue is brilliantly written, with such a flair for ostentatious Southern swearing you’d never believe it was penned by an Irishman. By the end of the book the characters feel like old friends and you are sad to bid them farewell, and their backstories are so fascinating that at times you will forget to care about whether or not God ever gets what’s coming to him. An epic modern myth with plenty of Wild West style, Preacher is a singularly profound feat of storytelling that belongs on the shelf of any half-serious comic book academic.

The Sandman is the book you’ll find on the shelf of the completely serious comic academic. The incomparable Neil Gaiman took one of DC’s unused misfit classic characters and reimagined him as the king of his own vast empire of horrifying, fantastic mythology. Although it is a book that defies summarization, I am obligated to at least try. Morpheus, the Lord of Dreams, alias Oneiros, the Shaper of Form, also known as Kai’ckul, has been imprisoned by mortals for 70 years. Upon escaping he embarks on a quest to retrieve his various artifacts of power so that he can return to his realm and reclaim his throne. After meeting with his dysfunctional family of immortal embodiments of abstract universal forces like Destiny, Despair, and Death, the Sandman learns he hasn’t been a very nice guy for the last few billion years, so he decides to walk through the waking world and visit the various otherworlds of DC Comics to try to learn how to change. It’s complicated. Fortunately, this book has been the subject of passionate study for years. A number of academic papers have been published about it, and there is at least one college professor in New York who teaches a course dedicated exclusively to deconstructing The Sandman. Someday Gaiman’s Sandman will be considered as unquestionably canonical as Joyce’s Ulysses.

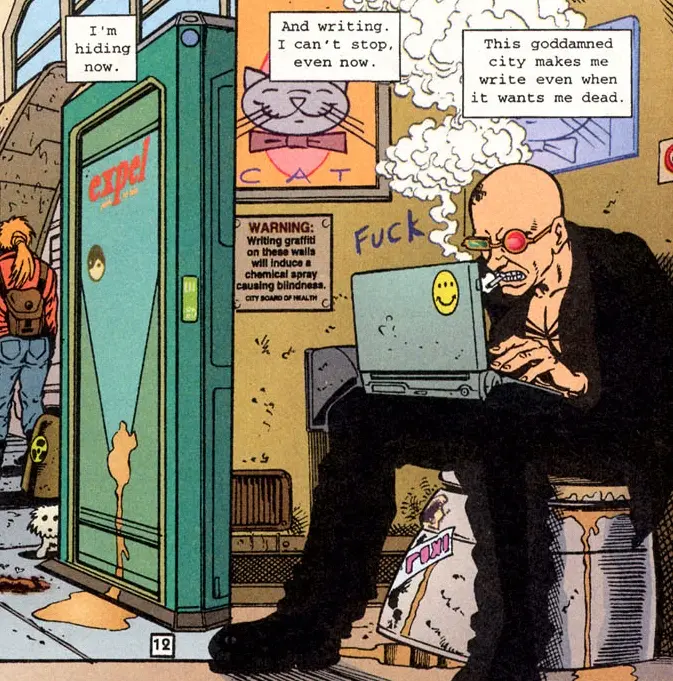

Transmetropolitan, by contrast, is the book on this list that has received almost no literary accolades outside of the comics industry, and has never received much academic attention, despite the fact it is most often discovered by college students who have stumbled across one of the many worlds of Warren Ellis and then eagerly consume his entire back catalog. This is a shame, because Transmetropolitan is a dense, multilayered cyberpunk vision that only becomes more relevant with age. Spider Jerusalem is a loving tribute to mad genius Hunter S. Thompson. He is the gonzo journalist of tomorrow, covering the awesome and terrible events that transpire in the distant future dystopia known  only as the City. It’s a surreal, self-centered consumerist paradise where a new religion is founded every six hours, people download newsfeeds direct to their subconscious through info pollen, and if you get tired of your body, you can download your brain into a new one, or a cloud of nanites. Armed with only a typewriter, his signature eyewear, a few firearms and an illegal bowel disruptor, Spider seeks out the naked ugly truth with devout obsession. In his weekly column for The Word, Spider writes about peaceful protests turned into violent race riots, the institutional marginalization of fringe cultures, corporate manipulation of private citizens, and of course, corrupt politicians. When Spider tries to expose a mad presidential candidate who only sees power as a tool to punish the people he hates, his writings are blocked from publication by governmental gag orders. Spider Jerusalem goes underground and becomes the archetype for the mythical superhero blogger, finding out the unknowable and printing it no matter what. With every passing year Transmetropolitan seems less like science fiction and more like a disturbingly prescient prophecy. Let us hope that one day in the distant future they will regard this book as a quaint paranoid fantasy of a simpler time.

only as the City. It’s a surreal, self-centered consumerist paradise where a new religion is founded every six hours, people download newsfeeds direct to their subconscious through info pollen, and if you get tired of your body, you can download your brain into a new one, or a cloud of nanites. Armed with only a typewriter, his signature eyewear, a few firearms and an illegal bowel disruptor, Spider seeks out the naked ugly truth with devout obsession. In his weekly column for The Word, Spider writes about peaceful protests turned into violent race riots, the institutional marginalization of fringe cultures, corporate manipulation of private citizens, and of course, corrupt politicians. When Spider tries to expose a mad presidential candidate who only sees power as a tool to punish the people he hates, his writings are blocked from publication by governmental gag orders. Spider Jerusalem goes underground and becomes the archetype for the mythical superhero blogger, finding out the unknowable and printing it no matter what. With every passing year Transmetropolitan seems less like science fiction and more like a disturbingly prescient prophecy. Let us hope that one day in the distant future they will regard this book as a quaint paranoid fantasy of a simpler time.

Watchmen is the sacred cow of comic books. It gets all the praise and makes all the lists. It won the 1988 Hugo Award and was the first comic book Time magazine ever mentioned without disdain. Libraries started ordering the collected editions for their shelves, and suddenly the graphic novel became a commercially viable format. This book truly earned its distinction as a novel—the illustrated panels are dense with text, and chapters are bookended by excerpts from Under the Hood, a fictitious novel written by one of the characters about his career as a costumed adventurer. The story takes place in 1985, in an alternate world where Nixon is still president and the nuclear deterrent is a blue science god. Superheroes were once common, but have been recently outlawed. A comedian dies in New York. Someone is killing masked avengers. The blue savior departs for Mars as the Americans and Russians drag race to Armageddon. Who will save us from ourselves? With its complex characters and metafictional awareness, Watchmen defiantly asserted that illustrated adventures could be just as literary as books that only have pictures on the cover. By the nebulous authority of THEY it has been declared the best graphic novel ever, so you better just go ahead and read it if you haven’t already. None of which is meant to imply that any of it is undeserved. There’s a reason it’s the all-time best seller—it’s really good. Watchmen took a bunch of old unused characters and gave them a dark and edgy revision dripping with pathos before it was the thing to do. Alan Moore’s brilliant deconstruction of the superhero mythos showed the world what the medium was truly capable of, and inspired generations of imitators. Some say it’s never been surpassed; others would argue. Regardless, it remains the most discussed and dissected graphic novel of the day, the subconscious standard by which all superhero sagas are measured.

There you have it—five of the most commonly discussed graphic novels. They may or may not be the best, but people who talk about comic books will refer to these works often. Of course this list is not complete. I’m sure our readers can name countless titles that absolutely belong in the hallowed comic book canon, and most of them are probably right. This list is really just a primer for those who want to dive in to the discussion of comics, or who just want to see some of the best the medium has to offer. As the conversation is ever ongoing, you can expect future posts to expand and add to the canon at length. You can start now. Make a case for why your sacred cow deserves the distinction of comic book canon in the comments section, and keep the dialog going.

About the author

BH Shepherd is a writer and a DJ from Texas. He graduated from Skidmore College in 2005 with degrees in English and Demonology after writing a thesis about Doctor Doom. A hardcore sci-fi geek, noir junkie and comic book prophet, BH Shepherd has spent a lot of time studying things that don’t exist. He currently resides in Austin, where he is working on The Greatest Novel Ever.